Oct 20 to Oct 26

After a day of fighting, the Japanese Army’s Second Division was resting when a curious delegation of two Scotsmen and 19 Taiwanese approached their camp.

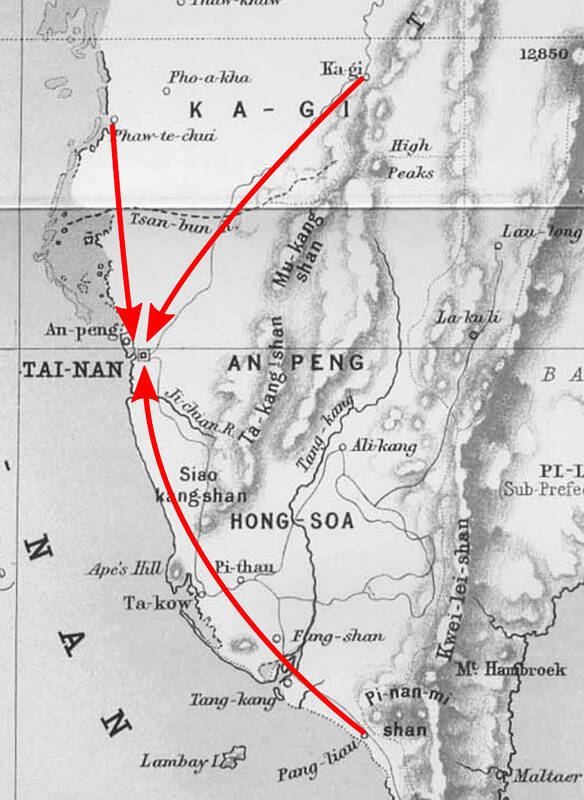

It was Oct. 20, 1895, and the troops had reached Taiye Village (太爺庄) in today’s Hunei District (湖內), Kaohsiung, just 10km away from their final target of Tainan.

Graphic: Han Cheung

Led by Presbyterian missionaries Thomas Barclay and Duncan Ferguson, the group informed the Japanese that resistance leader Liu Yung-fu (劉永福) had fled to China the previous night, leaving his Black Flag Army fighters behind and the city in chaos. On behalf of the local gentry, they asked the Japanese to enter peacefully to restore order and prevent further bloodshed.

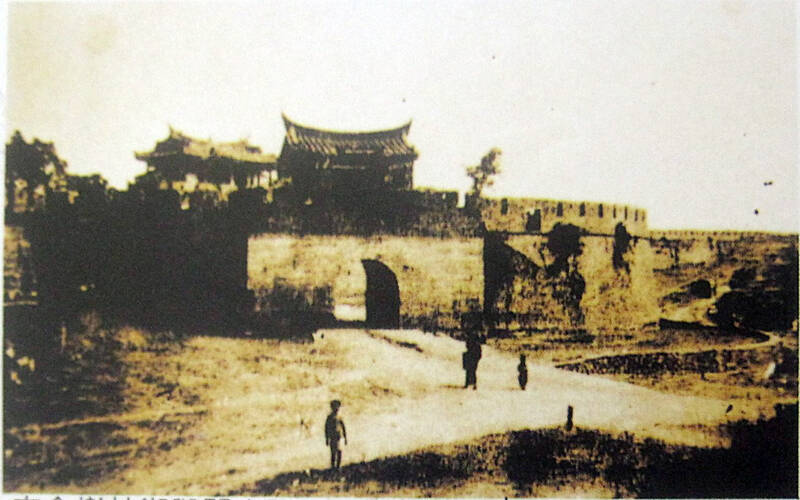

Around 6:30am the following morning, Major General Motomi Yamaguchi led a contingent of Japanese troops toward the city, accompanied by the missionary delegation. The Japanese were suspicious, but as promised, they entered from the South Gate without firing a shot.

Next week marks the 130th anniversary of the city’s capitulation, and although unrest continued in various regions, the Japanese regarded Taiwan (at least its western half) as “pacified.” Cheng Tao-tsung’s (鄭道聰) new book Taiwan Becomes a Foreign Land, Japanese Don’t Wear Queues (台灣變番邦 日本無頭鬃) details the more than 40 skirmishes fought between Oct. 10 and Oct. 21, a period often overlooked when discussing this war.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

REPUBLIC OF FORMOSA

Earlier this year, “Taiwan in Time” ran a four-part series on the Hakka resistance against the Japanese advance — first in northern and central Taiwan, then in Pingtung after the fall of Tainan. They were often supported by Liu’s Black Flag Army, which was based in Tainan. According to legend, Hakka militia leader Hsu Hsiang (徐驤) fought all the way from Hsinchu to northern Tainan, making his last stand at the Tsengwen River (曾文溪) on Oct. 20 (see “Taiwan in Time: The last Hakka musketeer,” June 29, 2025.

Liu and his troops first arrived in Taiwan in 1894 during the First Sino-Japanese War, which concluded with the Qing Empire ceding the island to Japan. Qing officials and local elites declared the Republic of Formosa in response, hoping to prevent Japanese occupation. They recruited Liu, and tasked him with defending Tainan.

Photo courtesy of National Museum of Taiwan History

The Japanese landed in Keelung on May 29, 1895, and the republic’s president Tang Ching-sung (唐景崧) soon fled to China. Although Liu declined the presidency, he effectively became the republic’s de facto leader by late June.

As the Japanese pushed their way south, Liu repeatedly asked Qing official Zhang Zhidong (張之洞) for reinforcements — to no avail. In August, Liu began issuing stamps and banknotes in Tainan under the name of the Republic of Formosa.

In late September, local militias and the Black Flags launched one final offensive northward, assaulting Japanese-occupied Changhua. After suffering heavy casualties and exhausting their ammunition, they could only fall back to a defensive position.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

VALIANT LOCAL MILITIAS

Liu instructed the Black Flags to guard the major ports, while local leaders raised troops to defend the river crossings and main roads. According to Cheng, this effort involved about 12,000 Black Flag soldiers and 8,000 Taiwanese fighters.

Meanwhile, the Japanese decided on a three-pronged attack of Tainan. Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa’s Imperial Guards Division, which had been the main invasion force since May, would continue its advance. The Fourth Mixed Brigade, under Prince Fushimi Sadanaru, was to land at Budai Port (布袋) in Chiayi, while Lieutenant General Nogi’s Second Division would land in Pingtung’s Fangliao (枋寮) and strike from the south. They totalled about 37,000 troops.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

On Oct. 11, the 12,000-strong Fourth Mixed Brigade completed its landing in Budai and headed toward Yanshuei (鹽水). A regiment of the Imperial Guards arrived first, driving off about 200 local fighters. They spent the night there before occupying Sinying (新營) the following day.

Over the next few days, the different regiments were repeatedly ambushed by the militias, who often surrounded them from all directions using the Songjiang Battle Array (宋江陣), a traditional formation accompanied by drums and gongs. After each assault, the fighters retreated into the brush. Although they managed to inflict casualties, they eventually succumbed to superior firepower.

Starting on Oct. 14, the Japanese began brutal punitive campaigns against the villages suspected of harboring fighters. Bloody battles broke out across today’s Beimen (北門), Jiali (佳里) and Shanhua (善化) districts, leaving countless dead. Many temples in the area commemorate those who fell during the fighting.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

TAINAN SURRENDERS

By early October, the Black Flag Army’s discipline had collapsed, often fleeing at the sight of the Japanese and leaving their cannons to local militias. Some even returned to Tainan to harass wealthy residents, many of whom fled to the countryside or to China.

A popular song described this situation: “Imperial envoy Liu’s plans failed to work, the flies have turned into bees, and the worms have turned into centipedes. The mansions are now empty, Taiwan is now a foreign land, and Japanese don’t wear queues.”

After several unsuccessful attempts to sue for peace, Liu fled to China on Oct. 19.

Meanwhile, Nogi’s Second Division fought their way north from Fangliao. After encountering unexpected resistance from the Hakkas (see “Taiwan in Time: Taiwan in Time: Burning the Hakka resistance to the ground,” July 6, 2025), they captured Fengshan (鳳山).

The Black Flags along this route were more active. On the morning of Oct. 20, the Japanese clashed with several hundred of them by the Ertsenghang River (二層行溪) and camped that night at Taiye Village. This is when the missionary delegation approached.

Barclay and Ferguson’s colleague William Campbell was not in Tainan at that time, but he details the surrender in Sketches From Formosa: “Hundreds of gentry came forward bowing their heads to the ground, and in a minute more the flag of the rising sun was waving over the city.”

A Japanese embedded reporter noted in Observations from the Taiwan Campaign that as the Japanese entered Tainan, residents stood in front of their homes, displaying a white flag signifying their submission to the Japanese Empire.

The Japanese then dispatched troops to Anping Fort, killing more than 50 Black Flags and capturing between 4,000 and 7,000, who were soon deported back to China. On Nov. 13, the Imperial Guard Division headed back to Japan, sans Prince Yoshihisa who died on Oct. 28 presumably of illness.

Nogi took charge of the defense of southern Taiwan, and on Nov. 18, governor-general Kabayama Sukenori officially declared the island “pacified.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name

There is no question that Tyrannosaurus rex got big. In fact, this fearsome dinosaur may have been Earth’s most massive land predator of all time. But the question of how quickly T. rex achieved its maximum size has been a matter of debate. A new study examining bone tissue microstructure in the leg bones of 17 fossil specimens concludes that Tyrannosaurus took about 40 years to reach its maximum size of roughly 8 tons, some 15 years more than previously estimated. As part of the study, the researchers identified previously unknown growth marks in these bones that could be seen only