Nov. 17 to Nov. 23

When Kanori Ino surveyed Taipei’s Indigenous settlements in 1896, he found a culture that was fading. Although there was still a “clear line of distinction” between the Ketagalan people and the neighboring Han settlers that had been arriving over the previous 200 years, the former had largely adopted the customs and language of the latter.

“Fortunately, some elders still remember their past customs and language. But if we do not hurry and record them now, future researchers will have nothing left but to weep amid the ruins of Indigenous settlements,” he wrote in the Journal of the Anthropological Society of Tokyo.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The first place Ino visited was Kipatauw, in today’s Beitou District (北投). (There are many spelling variations, but the Dutch-era “Kipatauw” remains the most common.) He counted 117 residents, noting that their clothing, dwellings and food were identical to the Han, although women still wore their hair in the traditional style: parted in the front and wrapped with black cloth at the back. Only those over 60 could remember fragments of their language, but they preserved many old objects and knew their traditional names.

By that time, their territory had shrunk considerably, consisting of the upper settlement by today’s Guizikeng (貴子坑), the middle settlement near Fuxinggang (復興崗) and the lower settlement a short walk from Beitou MRT station.

The Japanese forcibly purchased the upper settlement, and around 1930 relocated the middle settlement to build a horse racing track. Many residents moved to the lower settlement, which survived as a mixed Indigenous-Han community until MRT construction six decades later greatly reduced its size, scattering the residents into the wider city.

Photo courtesy of National Museum of Taiwan History

Today, the Ketagalan presence in Beitou can still be found in two spiritual centers led by the Pan (潘) family, originally from Kipatauw’s upper settlement: Independence Presbyterian Church (自立長老會新北投教會) and Baode Temple (保德宮). Over the past few months, I’ve been conducting field research on the descendants of Kipatauw through the Tree Tree Tree Person Project (森人). This article is the first of a series that will be published over the coming months.

FIRST ENCOUNTERS

The term “Ketagalan” now refers collectively to the Pingpu (plains) Indigenous people stretching from northern Taoyuan to the Yilan coast. But it was Ino who first grouped them under the term; earlier records only referred to individual settlements or administrative districts. Communities spoke similar languages and communicated through the common trade tongue of Basay.

Photo courtesy of National Palace Museum

Like other Pingpu groups, they are not officially recognized — although that may change with the passing of the Pingpu Indigenous People’s Identity Act (平埔原住民族群身分法) on Oct. 18.

Much of what is known about early Kipatauw comes from colonial and Qing-era sources, since the Indigenous people left few written accounts.

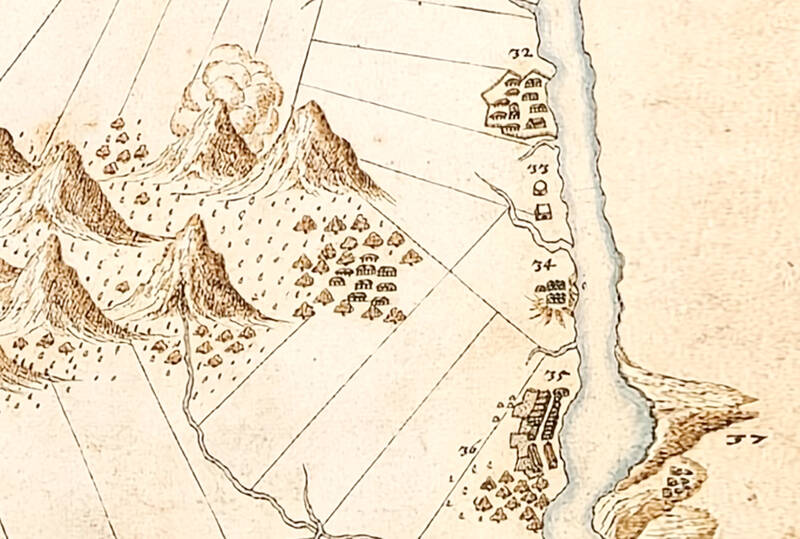

The first outsider to mention Kipatauw was likely Spanish missionary Jacinto Esquivel in 1632. He recorded the name as “Quipatao,” describing it as a group of eight or nine villages located along a small stream branching from the Keelung River near its split from the Tamsui River. Best accessed by boat, Kipatauw was located slightly inland and spared the floods that plagued some of the riverside communities. The residents had access to valuable sulfur deposits.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Aside from the coastal Taparri and Kimauri, who primarily engaged in fishing, trade and piracy, Esquivel wrote that most settlements relied on agriculture, the villagers rarely leaving except to hunt or farm.

The Dutch expelled the Spanish in 1642. The Diary of Fort Zeelandia records that on Sept. 23, representatives from Kipatauw arrived to pledge allegiance to the new authorities. The community of 160 people was led by chief Palijonnabos. The Dutch read them the conditions they were to follow, and presented them with a Prince’s Flag signifying Dutch protection. While villages were required to pay tribute, enforcement was inconsistent.

CONTACT AND CONFLICT

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Han traders visited the Tamsui area during Spanish times, but the Dutch encouraged them to settle there. A March 1646 entry in Diary of Fort Zeelandia notes that due to the scarcity of resources up north, any Han who wanted to farm, fish or do other trades there were exempt from taxation.

In 1655, Indigenous communities rose up against the Dutch. Kipatauw joined their neighbors and attacked the Han quarters in Tamsui the following year, killing three residents and burning down their houses. The Dutch were unable to respond until reinforcements arrived in September 1657. They summoned all local chiefs to negotiate, but three settlements, including Kipatauw, repeatedly refused and even taunted them. After a prolonged battle, the Dutch burned down their houses and fields.

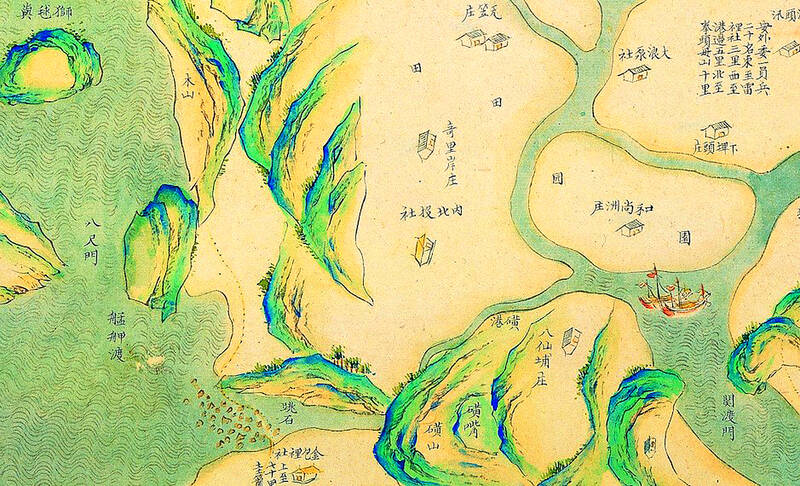

The next major record appears in 1697, when Qing envoy Yu Yung-ho (郁永河) arrived to obtain sulfur for Fujian Province after a fire destroyed its supply. He set up a refining camp in the Tamsui area and was visited by chiefs from 23 nearby settlements, including Inner and Outer Kipatauw — written with the same Chinese characters used today for Beitou. Yu welcomed them with wine, sugar balls and bolts of cloth in exchange for acid sulfate soil. (Today, “Kipatauw” generally refers to the inner settlement).

Yu later traveled deeper into Kipatauw territory by boat to find the source of the sulfur. The settlement was surrounded by dense forests and tall reeds, and he hired locals to help refine the sulfur. He noted that they could not understand each other’s languages.

Few Han people at the time lived near Kipatauw. But things would change within a few decades as settlers poured in mostly from Fujian Province.

HAN EXPANSION

By 1740, small Han communities dotted the area, including Beitou Village (北投庄), writes Liang Ting-yu (梁廷毓) in “History of Kipatauw: An Examination and Reflection on Indigenous–Han Relations” (北投社史: 一個原、漢關係的考察與反思).

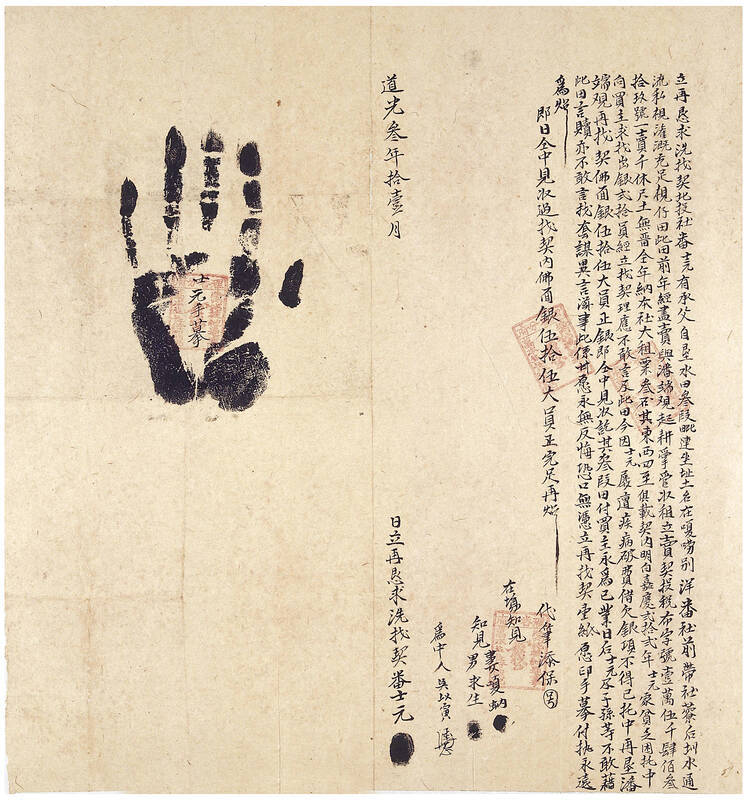

These settlers often encroached on Indigenous land, prompting officials to erect stone steles to mark boundaries. One of them, originally located in Beitou’s Huangxi Village (磺溪庄), stands today in front of Shipai MRT Station. Liang writes that there were fewer conflicts in Kipatauw, as most Han settlers rented land from the Indigenous people. However, in 1885, the Qing Dynasty government reduced the amount of rent Indigenous landlords could collect, hastening their decline.

Meanwhile, Han migration continued, and the settlers soon far outnumbered the Indigenous community, surrounding them on all sides. In 1758, the Qing court began compelling the Pingpu to adopt Han customs, and in the following year, the Qianlong Emperor granted them Chinese surnames.

By the time the Tamsui Subprefecture Annals (淡水廳志) were published in 1871, Pingpu culture was in steep decline. “Today, from Dajia (大甲) to Keelung, the Indigenous population has gradually declined, and their villages are scattered and desolate. In their dwellings, food, clothing, marriage, funerals and utensils, they have adopted about half of Han customs. Only two or three out of 10 are fluent in their language.”

When Ino visited Kipatauw 25 years later, the assimilation process was mostly complete. Next week’s feature will explore his expeditions, which laid the foundation for future ethnographic studies.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Today Taiwanese accept as legitimate government control of many aspects of land use. That legitimacy hides in plain sight the way the system of authoritarian land grabs that favored big firms in the developmentalist era has given way to a government land grab system that favors big developers in the modern democratic era. Articles 142 and 143 of the Republic of China (ROC) Constitution form the basis of that control. They incorporate the thinking of Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙) in considering the problems of land in China. Article 143 states: “All land within the territory of the Republic of China shall