Seven hundred job applications. One interview.

Marco Mascaro arrived in Taiwan last year with a PhD in engineering physics and years of experience at a European research center.

He thought his Gold Card would guarantee him a foothold in Taiwan’s job market.

Photo courtesy of the Taiwan Employment Gold Card Office

“It’s marketed as if Taiwan really needs you,” the 33-year-old Italian says. “The reality is that companies here don’t really need us.”

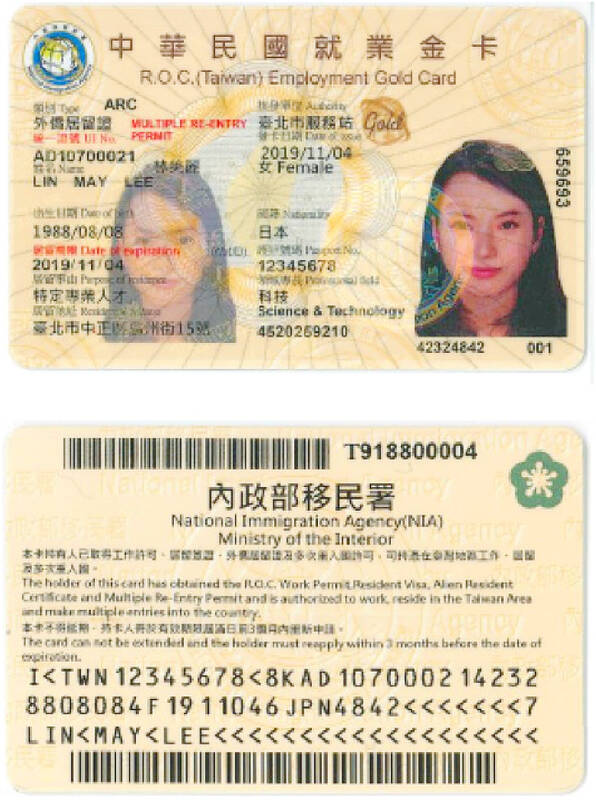

The Employment Gold Card was designed to fix Taiwan’s labor shortage by offering foreign professionals a combined resident visa and open work permit valid for three years.

But for many, like Mascaro, the welcome mat ends at the door.

Photo courtesy of the Taiwan Employment Gold Card Office

A DEMAND PROBLEM

The government in 2020 set an ambitious goal of attracting 400,000 foreign professionals by 2030 to offset a projected labor shortage of up to 480,000 workers, according to the National Development Council.

That goal was revised last year to 120,000 by 2028, with 60,000 expected to come through professional talent.

Photo: Billy Wu

“The new target is more realistic,” says Suen Hung-yue (孫弘岳), a professor at National Taiwan Normal University’s Department of Technology Application and Human Resource Development.

The shift reflects a clearer focus on white-collar talent needed in sectors such as semiconductors and IC design. But Suen notes that this creates a fundamental mismatch between policy and reality.

“When Taiwan talks about a labor shortage, it’s really talking about a shortage of cheap labor,” he says. “The gaps are in traditional manufacturing and service jobs.”

Photo courtesy of Luna Luovula

In other words, the industries facing the most urgent labor shortages are those least likely to hire foreign talent.

The economic context compounds the challenge. According to CEOWORLD magazine, Taiwan ranks 41st globally in after-tax income, below Japan, South Korea and Hong Kong.

Only the semiconductor or tech sector actively seeks talent and offers salaries high enough to attract people from overseas.

Photo courtesy of Marco Mascaro

A 2023 survey found 30.8 percent of Gold Card holders work remotely for foreign employers, often as freelancers or digital nomads. Only 24.4 percent work for Taiwanese companies.

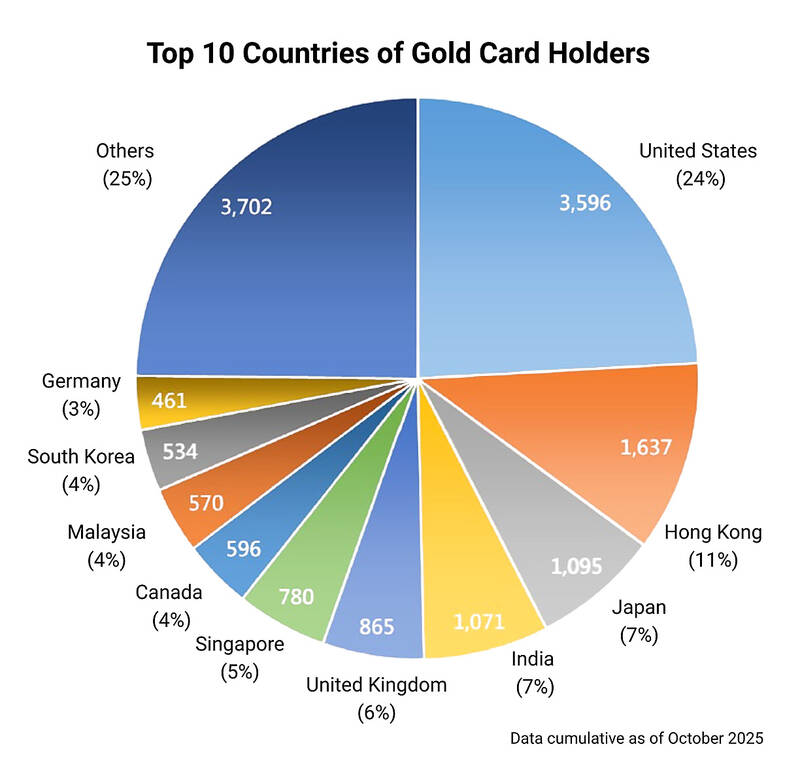

Though more than 14,000 Gold Cards have been issued since the program’s launch in 2018, many recipients never enter Taiwan’s domestic workforce.

Many already had prior ties to Taiwan before applying, meaning that what drew them was not the job market, but Taiwan itself.

Photo courtesy of National Development Council

“The Gold Card is a great entry tool,” Suen says. “But we still don’t have an environment that can attach or integrate them.”

NO PLACE TO ATTACH

Most of the criticism the Gold Card program has faced is not with the policy itself, but Taiwan’s long-standing structural barriers.

The first wall is language. Tammy Huie (許婉婷), a 32-year-old information security professional from the US, describes the employment reality bluntly: “If you don’t want to become an English teacher and you’re not willing to learn Mandarin, your chances of finding a job here are almost zero.”

Mascaro was enrolled in an intensive Mandarin course at National Taiwan Normal University, but found the programs inadequate.

“They focus on character writing and reading,” he says. “But as a newcomer, you want to communicate orally.”

Beyond language, Taiwan’s systems are not designed to integrate foreigners. Even routine procedures can become hurdles.

Matteo Serone, a former Gold Card holder, recalls being asked to pay a NT$2,000 deposit to open a mobile phone account simply because he was a foreigner.

Foreign residents’ identification numbers contain an 8 or 9 as the second character, which many systems reject as invalid. Online banking platforms often refuse their applications as a result.

At the root of these challenges is Taiwan’s household registration system, or huji (戶籍), which forms the basis of citizenship and access to most government and financial services.

Without it, foreigners face limited access to financial and social services.

Gold Card holders can apply for an Alien Permanent Resident Certificate (APRC) after three years and obtain household registration afterward.

Yet achieving true equality remains difficult, as naturalization still requires renouncing one’s original nationality.

“If Taiwan itself lacks confidence in opening up its systems, and the policies are full of restrictions,” Suen says, “it will hinder our ability to attract foreign talent.”

Despite these barriers, some choose to stay out of personal attachment, not institutional support.

Mascaro kept reaching out to companies despite repeated rejections. Luna Luovula, a 33-year-old tap dancer from Finland who co-founded an AI startup, even sought therapy to better understand how to adapt rather than leave.

In the end, retention often depends less on policy than on individual resilience.

A SYSTEM BEYOND COORDINATION

Daily problems from banking to healthcare require coordination across multiple ministries, but Suen says Taiwan’s bureaucracy lacks horizontal communication.

“Departments operate independently with their own key performance indicators,” he says.

The Taiwan Employment Gold Card Office, established in 2020, was meant to bridge those gaps for cardholders.

Two years ago, the Taipei Times reported on the office’s efforts to address these systemic challenges. Most of those problems remain.

When asked about concrete progress and results, the office offered few details.

“I hear less problems in banking,” Director Jonathan Liao (廖炳坤) says. “Some people are satisfied.”

But there is still no data on how many Gold Card holders have successfully opened bank accounts or whether success rates have improved.

Liao says that overseas promotional campaigns in India have helped boost the country’s ranking to fourth among Gold Card source nations in recent years.

Yet Mascaro says those campaigns create false expectations.

“When they were doing campaigns around the world, they also invite companies like Google, “ he says. “They made it sound like you come here and can find a job the day after.”

Some cardholders argue that the burden shouldn’t fall entirely on the government.

“You don’ t come in expecting the red carpet to be rolled out,” Huie says, noting that the office does hold regular consultation hours for cardholders.

Still, one small office cannot solve communication problems across Taiwan’s entire bureaucracy.

And while it has made incremental progress, institutional support remains too limited to help most Gold Card holders truly integrate into Taiwanese society.

A SIGN OF INTENT

Recent legislative changes suggest the government is aware of these challenges.

Lawmakers in August amended the Act for the Recruitment and Employment of Foreign Professionals (外國專業人才延攬及僱用法), allowing foreign professionals to join Taiwan’s national labor pension system before obtaining permanent residency.

Other initiatives include Bilingual Nation 2030, English-friendly infrastructure and broader talent-attraction policies.

Mascaro’s case, however, reveals a deeper mismatch between policy ambition and reality.

If Taiwan wants to be an international talent hub, Suen says, what needs to change is “the very structure of Taiwan’s industries.”

With 2028 just three years away, it remains unclear what share of the 60,000 target the Gold Card program is expected to deliver or whether ongoing reforms are keeping pace with labor demand.

“For attraction, the program works well,” Mascaro says. “The problem is retention.”

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality