Growing up in North Korea, Hyuk’s childhood was about survival. He never listened to banned K-pop music but, after defecting to the South, he’s about to debut as an idol.

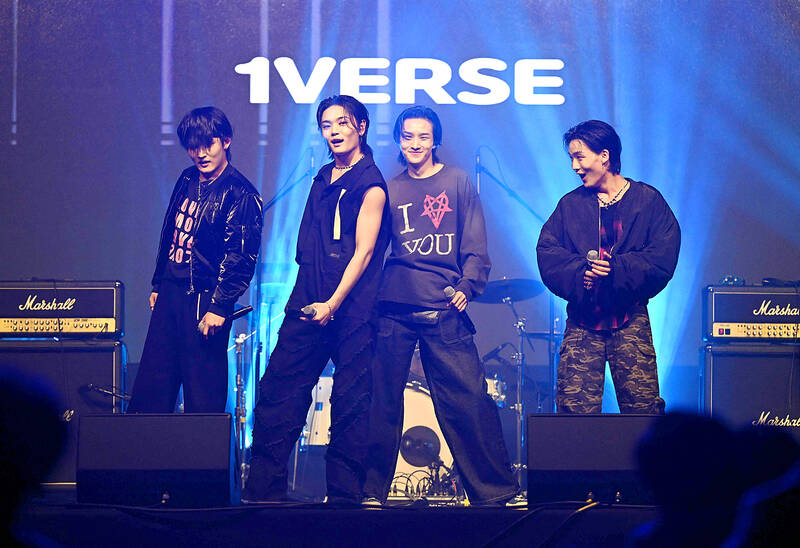

Hyuk is one of two young North Koreans in a new K-pop band called 1Verse — the first time that performers originally from the nuclear-armed North have been trained up for stardom in South Korea’s global K-pop industry.

Before he was 10, Hyuk — who like many K-pop idols now goes by one name — was skipping school to work on the streets in his native North Hamgyong province and admits he “had to steal quite a bit just to survive.”

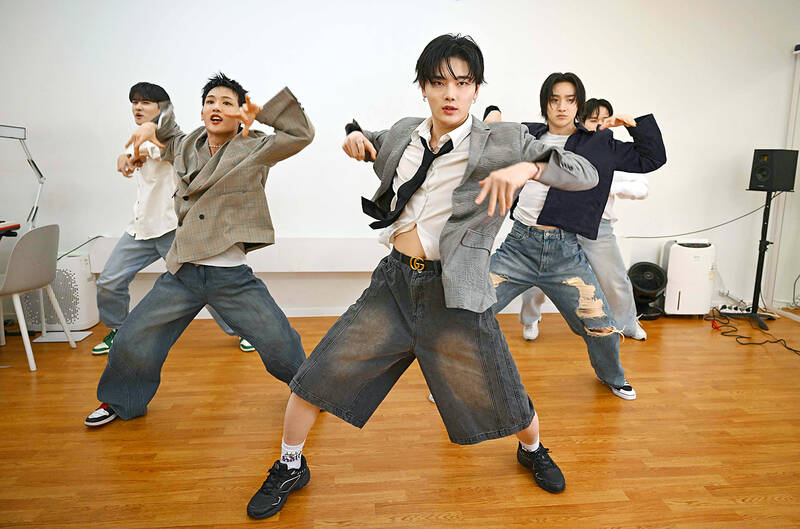

Photo: AFP

“I had never really listened to K-pop music”, he said, explaining that “watching music videos felt like a luxury to me. My life was all about survival,” he said, adding that he did everything from farm work to hauling shipments of cement to earn money to buy food for his family.

But when he was 13, his mother, who had escaped North Korea and made it to the South, urged him to join her.

He realized this could be his chance to escape starvation and hardship, but said he knew nothing about the other half of the Korean peninsula.

Photo: AFP

“To me, the world was just North Korea — nothing beyond that,” he said.

His bandmate, Seok, also grew up in the North — but in contrast to Hyuk’s hardscrabble upbringing, he was raised in a relatively affluent family, living close to the border.

As a result, even though K-pop and other South Korean content like K-dramas are banned in the North with harsh penalties for violators, Seok said “it was possible to buy and sell songs illegally through smugglers.”

Thanks to his older sister, Seok was listening to K-pop and even watching rare videos of South Korean artists from a young age, he said.

“I remember wanting to imitate those cool expressions and styles — things like hairstyles and outfits,” Seok said.

Eventually, when he was 19, Seok defected to the South. Six years later, he is a spitting image of a K-Pop idol.

STAR QUALITY

Hyuk and Seok were recruited for 1Verse, a new boy band and the first signed to smaller Seoul-based label Singing Beetle by the company’s CEO Michelle Cho.

Cho was introduced to both of the young defectors through friends.

Hyuk was working at a factory when she met him, but when she heard raps he had written she said that she “knew straight away that his was a natural talent.”

Initially, he “professed a complete lack of confidence in his ability to rap,” Cho said, but she offered him free lessons and then invited him to the studio, which got him hooked.

Eventually, “he decided to give music a chance,” she said, and became the agency’s first trainee.

In contrast, Seok “had that self-belief and confidence from the very beginning,” she said, and lobbied hard to be taken on.

When Seok learned that he would be training alongside another North Korean defector, he said it “gave me the courage to believe that maybe I could do it.”

‘WE’RE ALMOST THERE’

The other members of 1Verse include a Chinese-American, a Lao-Thai American and a Japanese dancer. The five men in their 20s barely speak each other’s languages.

But Hyuk, who has been studying English, says it doesn’t matter.

“We’re also learning about each other’s cultures, trying to bridge the gaps and get closer little by little,” he said.

“Surprisingly, we communicate really well. Our languages aren’t perfectly fluent, but we still understand each other. Sometimes, that feels almost unbelievable.”

Aito, the Japanese trainee who is the main dancer in the group, said he was “fascinated” to meet his North Korean bandmates.

“In Japan, when I watched the news, I often saw a lot of international issues about defectors, so the overall image isn’t very positive,” he said.

But Aito said his worries “all disappeared” when he met Hyuk and Seok. And now, the five performers are on the brink of their debut.

It’s been a long road from North Korea to the cusp of K-pop stardom in the South for Hyuk and Seok — but they say they are determined to make 1Verse a success.

“I really want to move someone with my voice. That feeling grows stronger every day,” Seok said.

Hyuk said being part of a real band was a moving experience for him.

“It really hit me, like wow, we’re almost there.”

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand