Oct 16 to Oct 22

In 1939, an eight-year-old Archibald Chien (簡錦錐) was captivated by the sight and smells of the Russian-run Cafe Astoria, located on Shanghai’s trendiest Xiafei Road (霞飛路). There was no time to linger, as the ship back to Taiwan was about to depart.

Chien had spent just over a month visiting his brother in the Japanese-occupied city, and was preparing to head home to Taiwan.

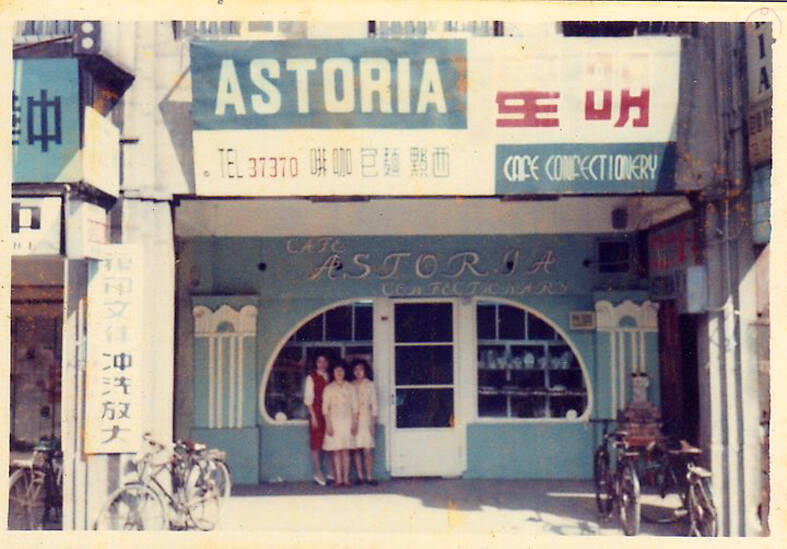

Photo courtesy of National Central LIbrary

It was unusual for a child to travel alone, and the elder brother entrusted a passenger to look after Chien during the journey. Chien wasn’t nervous; he couldn’t wait to tell his mother about the extraordinary things he experienced abroad. After disembarking at Keelung, he managed to make it home to Sinjhuang (新莊) by himself, Hsieh Chu-fen (謝祝芬) writes in the book, Cafe Astoria Confectionary (明星咖啡館).

Fate would have it that 10 years later, one of the Shanghai cafe’s owners who fled to Taiwan enlisted Chien’s help in launching a store of the same name in Taipei. Opening in October 1949, it was the city’s first Western pastry shop, and is reputed to have introduced the tradition of birthday cakes to Taiwan.

Chien became the cafe’s sole proprietor in 1961, giving it the Chinese name “Bright Star” (明星) in 1964. It closed down in 1989, but reopened in 2004 and remains in business today.

Photo courtesy of Cafe Astoria

BIRTH OF ASTORIA

After World War II, Chien moved to Taipei to study and help out at his aunt’s store, which was frequented by Westerners to exchange currency. One of their customers was George Elsner, a Russian royal who fled the Bolshevik Revolution at the age of 22 to Shanghai.

Chien had learned some English, and through Elsner, other Russians came to the shop to ask for his help with translation and other tasks. Although anti-Soviet sentiment was strong in Taiwan, Chien didn’t understand the political situation, and at first he thought they were Americans since they communicated with him in English. He became good friends with them, and they began calling him “Archie” from his Chinese nickname A-chui.

Photo courtesy of Cafe Astoria

One day, Elsner, who sorely missed eating Russian bread, asked Chien if he wanted to help open up a Western-style pastry shop. Chien agreed and found a storefront that nobody wanted to rent as it was across the street from the City God Temple, which was considered bad luck. The Russians didn’t mind, and were even more pleased after learning that the address plate was No. 7 — which they considered auspicious.

After securing funding, Chien negotiated with the property owner, future Taipei mayor Henry Kao (高玉樹). Kao was reluctant due to Chien’s age and the other owners being Russian, and doubled the listing price. After Chien proved that these Russians were exiles who had no association with communism or the Soviet Union, and that they were willing to pay up, Kao relented.

Cafe Astoria opened on 7 Wuchang Street (武昌街7號), with the first floor as a bakery and second and third floors as a cafe. One of the proprietors was the former owner of the Cafe Astoria in Shanghai that Chien passed by as a child, and the store took on the same name.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Locals were shocked that someone dared renovate a building in front of the City God Temple, and they were just waiting for someting bad to happen. But after seeing content Westerners coming in and out of the shop and smelling the sweet aroma of bread and coffee, they also wanted to go in and have a try.

RUSSIAN HANGOUT

For its first few years, Cafe Astoria was a popular hangout for local Russians, who celebrated holidays, danced and drank vodka at the shop.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Many of them then had first fled the Soviets to China, then to Taiwan. Several part-owners of Cafe Astoria became nervous during the Korean War, fearing that Taiwan would also fall to the Chinese communists if things went south. One by one, they sold their shares to Chien and emigrated — even after purchasing the building in 1953.

As the Russian population in Taiwan dwindled, Elsner also wanted to leave. They decided to sell the business, but after a major dispute with the remaining owners, Elsner was left in financial straits. His plans to move to the US were dashed, yet he could not stay in Taiwan legally without a job. Having no passport, he had nowhere else to go. To help him out, Chien secretly took over and re-opened Cafe Astoria, hiring Elsner as a consultant and buying a flat for him to stay in.

By then, the distinct Russian flavor of the cafe was no more, and by the 1960s it was mostly offering Western specialties that suited Taiwanese tastes. Elsner remained in Taiwan for the rest of his life, visiting the cafe regularly even after multiple strokes, until his death in 1973.

Former first lady Faina Chiang Fang-liang (蔣方良), who was Russian, also frequented the cafe. She often turned up with her husband and future president Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國), who spent a decade in Russia and went by the name “Nikolai” in the shop.

LITERATURE HUB

As one of Taipei’s few Western cafes, Astoria was a hotspot for the city’s young intellectuals.

Noted author Kenneth Pai (白先勇) reminisces about his experiences in his 1979 essay Cafe Astoria (明星咖啡館). He and his friends began meeting there regularly as university students in the late 1950s, and he was particularly fond of the cake.

“In those days, going to a coffee shop in Taipei was still somewhat of a luxury ... Fortunately Astoria’s prices were not that steep; we could still afford it in moderation.”

At the store’s entrance was a bookstand run by poet Chou Meng-tieh (周夢蝶). Unlike other stalls it didn’t sell any newspapers, magazines or martial arts novels, only poetry collections and modern literature.

“This was the realm of Chou, the ruler of the ‘Country of Solitude,’” Pai writes, referring to the title of Chou’s first poetry collection.

Prior to settling in that spot, Chou carried around a piece of cloth and a box of books everyday and set up shop in an inconspicuous place until the police chased him away. The first day he arrived at Astoria, Chien’s wife greeted him and even gave him a piece of cake. Later, they let him install a bookshelf outside so he didn’t have to lug around his books each day. He also obtained a vendor license. Chou ran it from April 1, 1959 to April 1, 1980, joking to Hsieh that it was all an “April Fool’s story.”

In 1960, Pai launched the literary journal Modern Literature (現代文學). He regularly brought stacks of old, unsold copies to Chou’s stand.

“We let Chou place them on his throne, then we walked up the stairs to Astoria Cafe for a cup of rich coffee, enjoying a literary afternoon,” he writes.

Other literati also gathered there, and Pai met many now-renowned writers for the first time while hanging out in the cafe.

“During the early 1970s, Taiwan’s modern literature scene was still in its fledgling stages,” he writes. “In the eyes of the common people, we were eccentrics whom they could not understand. Most of what we wrote were merely passed around among friends, and the one or two compliments we received were the greatest encouragement …

“But just like that, amid the rich coffee aroma of Cafe Astoria, Taiwan’s modernist poems and novels quietly budded and blossomed.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand