Every morning in his refugee camp school, Mohammad Yusuf sings the national anthem of Myanmar, the country whose army forced his family to flee and is accused of killing thousands of his people.

Yusuf, now 15, is one of hundreds of thousands of mostly Muslim ethnic Rohingya who escaped into Bangladesh after the Myanmar military launched a brutal offensive five years ago on Thursday. For nearly half a decade, he and the vast numbers of other refugee children in the network of squalid camps received little or no schooling, with Dhaka fearing that education would represent an acceptance that the Rohingya were not going home any time soon.

That hope seems more distant than ever since the military coup in Myanmar last year, and last month authorities finally allowed UNICEF to scale up its schools program to cover 130,000 children, and eventually all of those in the camps.

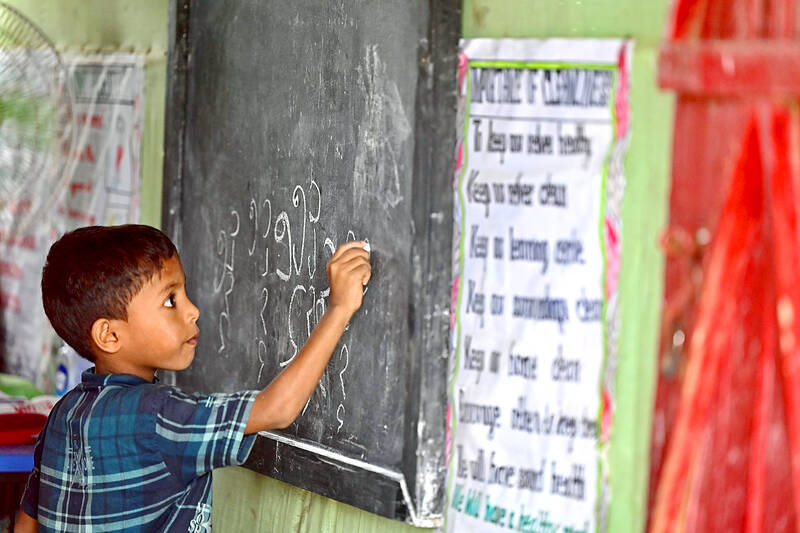

Photo: AFP

But the host country still wants the refugees to go back: tuition is in Burmese and the schools follow the Myanmar curriculum, also singing the country’s national anthem before classes start each day.

The Rohingya have long been seen as reviled foreigners by some in Myanmar, a largely Buddhist country whose government is being accused in the UN’s top court of trying to wipe out the people, but Yusuf embraces the song, seeing it as a symbol of defiance and a future return.

“Myanmar is my homeland,” he said. “The country did no harm to us. Its powerful people did. My young sister died there. Our people were slaughtered. “Still it is my country and I will love it till the end,” Yusuf said.

Photo: AFP

TICKING BOMBS

The denial of education for years is a powerful symbol of Bangladesh’s ambivalence towards the refugee presence, some of whom have been relocated to a remote, flood-prone and previously uninhabited island.

“This curricula reminds them they belong to Myanmar where they will go back some day,” deputy refugee commissioner Shamsud Douza said.

Photo: AFP

But when that might happen remains unclear, and visiting UN human rights chief Michelle Bachelet said this month that conditions were “not right for returns.”

Repatriation could only happen “when safe and sustainable conditions exist in Myanmar,” she added.

She dismissed the suggestion that the Rohingya camps could become a “new Gaza,” but Dhaka is now increasingly aware of the risks that a large, long-term and deprived refugee population could present.

Around 50 percent of the almost one million people in the camps are under 18.

The government “thought educating the Rohingya would give a signal to Myanmar that (Bangladesh) would eventually absorb the Muslim minority”, said Mahfuzur Rahman, a former Bangladeshi general who was in office during the exodus.

Now Dhaka has “realized” it needs a longer-term plan, he said, not least because of the risk of having a generation of young men with no education in the camps.

Already security in the camps is a major problem due to the presence of criminal gangs smuggling amphetamines across the border. In the last five years there have been more than 100 murders.

Armed insurgent groups also operate. They have gunned down dozens of community leaders and are always on the lookout for bored young men.

Young people with no prospects — they are not allowed to leave the camps — also provide rich pickings for human traffickers who promise a boat ride leading to a better life elsewhere.

All the children “could be ticking time bombs,” Rahman said. “Growing up in a camp without education, hope and dreams; what monsters they may turn into, we don’t know.”

LOST YEARS

Fears remain over whether Bangladesh may change its mind and shut down the schooling project, as it did with a program for private schools to teach more than 30,000 children in the camps earlier this year.

Some activists condemn the education program for its insistence on following the Myanmar curriculum, rather than that of Bangladesh. With few prospects of return, the Myanmar curriculum was of little use, said Mojib Ullah, a Rohingya diaspora leader now in Australia.

“If we don’t go back to our home, why do we need to study in Burmese? It will be sheer waste of time — a kind of collective suicide. Already we lost five years. We need international curricula in English,” he said.

Young Yusuf’s ambitions also have an international dimension, and in his tarpaulin-roofed classroom he read a book on the Wright brothers.

He wants to become an aeronautical engineer or a pilot, and one day fly into Myanmar’s commercial hub Yangon.

“Someday I will fly around the globe, that’s my only dream.”

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,