Abalmy summer night in 1985 found Paul Katz in Tainan standing amid screams and bloodletting. The young scholar had traveled thousands of kilometers from the relative calm of his leafy alma mater, Yale University, to enter a realm of ghosts and their hunters.

Two decades later, Katz — an Academia Sinica research fellow and a leading authority on Taiwanese religious phenomena — is still in that realm. For him, the study of religion is in itself a religion, and his baptism was literally one of fire: Taiwan's Burning Boat Festival (燒王船).

“The festival started with days of men lining up at temples to get whipped,” Katz told the Taipei Times. “Nominally, this kind of ritual is about driving out evil influences, but it also satisfies the psychological need to address guilt and sin.”

PHOTO COURTESY OF HUANG PING-YING

Next, ghost hunters — dance troupes wearing Chinese warrior outfits — took to the streets, twirling staffs and performing exorcisms.

“Ghost hunters typically congregate in places where a tragedy has occurred — at the site of a traffic accident, for example,” Katz said, adding that people who die violently become restless ghosts, according to the thinking associated with the Burning Boat Festival.

“Restless ghosts tend to haunt a particular area, oftentimes at the sites of their deaths, and it's up to ghost-hunting dancers to exorcise them,” Katz explained.

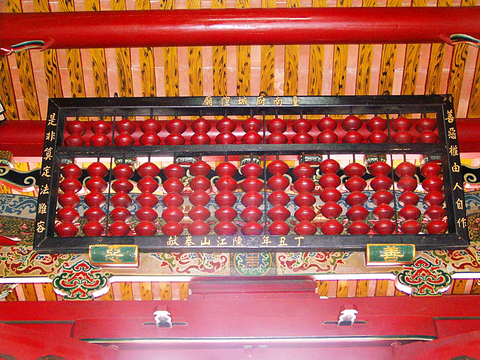

PHOTO: MAX HIRSCH, TAIPEI TIMES

The festival's climax is the torching of a giant boat.

The organizers spend hundreds of thousands of NT dollars and many months constructing the boats, said Katz. They stuff a ship with paper effigies of themselves and parade it through town. Then, they light it up at twilight and watch it burn.

“The wildest scenes took place at night, when all the processional troupes returned to the main temple,” Katz said.

PHOTO COURTESY OF HUANG PING-YING

“Imagine yourself standing on a dimly-lit street outside the front gates of a temple, watching troupes of grim-faced ghost dancers going through their paces, while dozens of spirit-mediums scream and beat themselves bloody. To make matters worse, a fight between rival troupes broke out ... and the police had to intervene. The tensions that were on display were ... shocking,” he said.

So began the young American's fascination with religion in Taiwan.

A history major at Yale, Katz was initially drawn to the study of violent rituals in European history. However, after attending a lecture by Jonathan Spence, a renowned Sinologist, and studying Chinese at Taiwan National University for a year (1984-1985), Katz became hooked on Taiwan and the dark side of its religiousness. His first Boat Burning Festival in 1985 sealed the deal: Katz returned to the US in 1985 to study Chinese religion at Princeton University, eventually earning a doctorate in Chinese History. He taught at a number of universities before becoming a researcher at Academia Sinica in 2002.

“That a foreigner can come to Taiwan and be an authority on Taiwanese religious phenomena is, I think, indicative of the inclusive, syncretic nature of religion here,” Katz said. He attributed such inclusiveness to Taiwan's history as an “island frontier.”

“Island cultures typically boast a rich tradition of trade and cultural exchange, and so are often fairly open to outside influences,” Katz said. He called Taiwan a “cosmopolitan” place, ideal for conducting field research. China, on the other hand, still lacks the openness necessary for conducting research, the researcher said, adding that the island's comparatively free and democratic society is why he settled here and not in China.

“Getting picked up in China for conducting field research is common ... . I have friends who have had to cool their heels in a Chinese jail for trying to observe a ritual or ceremony,” Katz said.

Taiwanese religious phenomena have proliferated in the face of modernity, Katz said, and that's why he feels at home in Taiwan.

One might expect that in many societies the rise of capitalism and science would rein in religious beliefs to a degree.

Not so in Taiwan.

With the advent of globalization and the digital age, the practice of religion in Taiwan has only intensified, according to Katz. Rituals and temples are now more relevant than ever in Taiwan, given the roles they play in helping people cope with the stresses and strains of modern life.

“Guilt and sin persist. Rites of affliction in which people punish themselves, are still very cathartic, therapeutic,” Katz said. He displayed pictures of Burning Boat Festival-goers submitting to whippings, and families tossing effigies of themselves into the boat to be burned.

“Then, of course, there are the economic and political aspects,” Katz said.

“As the process of localization in Taiwanese culture has gained momentum after the Martial Law era, temples have become nodes of power. We have our country clubs — the Taiwanese have their temples,” the scholar said. He cited politicians' high-profile visits to temples, saying that the way to power was through such religious hubs.

“Temples are also loaded with money; they're big business here,” Katz added. “And if you want backing and legitimacy as a leader, you need to court these local nodes of power.”

Temples, therefore, thrive in modern Taiwan by being politically-charged, monied institutions that can make or break politicians' and barons' careers, according to Katz.

They also continue to serve humans' ageless need to commune with something greater than themselves.

So what does Katz himself commune with or believe in?

“I believe in a greater power — not quite something like what's painted on the Sistine Chapel, but certainly a presence in the universe,” he said. Despite his keeping a “scholarly distance” from religion, Katz has witnessed many bizarre occurrences, and believes that “there is a [genuine] spiritual power out there, and some people can tap into it.”

“I've come across spirit-mediums who went into a trance and just knew things that they shouldn't have known. I've also seen festival-goers flagellate themselves, leaving nasty scars that heal up only moments later. Strange stuff,” Katz told the Taipei Times.

On the topic of local temples, the academic also explained the phenomenon of “ghost shrines” in Taiwan, which tend to pop up on roadsides and either grow and become grander, or peter out.

“Let's say a corpse washes up after a typhoon, or a person dies in a car crash. The townspeople will often erect a shrine to appease the person's ghost. Then, locals will visit the shrine, many of whom will make illegitimate requests. If their wishes come true, they repay the ghost by building up its shrine, making it huge and elaborate. Of course, if the visitors' wishes go unfulfilled, the shrine is gradually forgotten.”

Although Katz raises eyebrows in Taiwan for being a foreigner and an authority on its religious phenomena, for him, it's all just par for the course. After all, Taiwan's religious environment is a crossroads of traditions and cultures, and perhaps nobody is more qualified to appreciate that than a “foreigner.”

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)