Horrific science fiction in the West goes back at least to the English “gothic horror” novels of the late 18th century, of which Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is the best known. It continued through the works of Edgar Allan Poe, then Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and from there into a spawning world of American comics and similarly-inspired stories, of which those of H.P. Lovecraft are now seen as the summit.

It’s a world that undeniably has its roots in the human subconscious, with all its attendant fears, but it is also responsible for widespread urban myths such as having encountered aliens in their spaceships, and even having had sex with them.

In The Colour out of Space (1927), for example, Lovecraft creates a grotesque world in which a meteorite spreads unnatural horrors of every conceivable kind in a rural area of New England, horrors which even the projected flooding of the afflicted area with a reservoir can’t contain. The prose is replete with phrases such as “a glutted swarm of corpse-fed fireflies dancing hellish sarabands” and “the detestably sticky noise as of some fiendish and unclean species of suction,” together with trees that were “twitching morbidly and spasmodically, clawing in convulsive and epileptic madness at the moonlit clouds.”

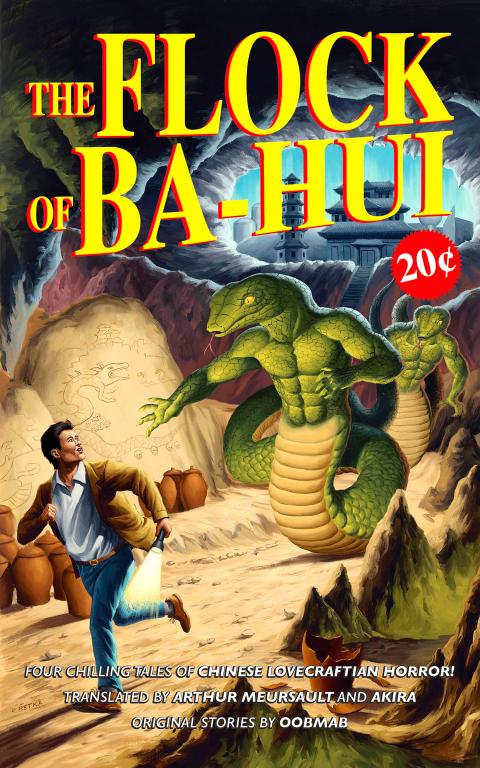

Taiwan’s Camphor Press has pioneered the translation into English of what is apparently a burgeoning school of Lovecraft imitators in China. This first title is The Flock of Ba-Hui, and it couldn’t be more Lovecraftian or more readable.

In the first tale, from which the collection takes its title, a dissident anthropologist escapes from a psychiatric hospital where he has been incarcerated. He’s never seen again, but it’s discovered he made his way to the mountains of western Sichuan Province on the trail of what he’s previously claimed was an unknown, pre-Chinese civilization. Four former colleagues follow his footsteps and are led to a gigantic, steeply-descending cave. As they go down into it they discover horrifying murals depicting human and other sacrifices on a vast scale, followed by cannibalism.

The narrator opts to go even deeper than the others and is eventually confronted with a huge green snake. At this point he passes out and is only rescued when his companions hear his terrified cries. But they refuse to believe his story, even though it conforms to local legend. And thus this highly Lovecraftian story ends.

In the second story, Nadir, an artist is described as living in a city north of which stands a gigantic tower that nobody dares climb. After a long voyage in which he sees all the beauties of the world, the artist decides to ascend the tower. After many days he finally reaches the top where he’s presented with the terrifying mysteries of the universe, a chaos beyond all known stars, a reality no human has ever seen.

This tale, the only one of the four not set in China, isn’t about horrifying snake-gods but about an immensity that, if not exactly beautiful, has all the awesomeness of the unknowable. It asks questions, and hints at answers, that no socially conventional fiction could possibly approach.

The third tale, “Black Taisui,” is set in Qingdao. It’s unusual for this book in beginning with a relatively recent event, a death in 2013, though much of its action takes place a hundred years earlier. Featured prominently are a secret society aiming at immortality, smuggling, and an old house that contains a subterranean ancestral hall from which emanates a terrible stench.

At one point what may be the taisui of the title is discovered — an abomination whose “whole body is smooth and black; it had neither head or tail: a bubbling mass of chaos with hundreds of eyes across its body staring in all directions and hundreds of mouths speaking in a thousand tongues.”

The modern setting is continued when a group of policemen communicating with their headquarters by radio enter the sewer system only to find corpses that have turned into a black mucus, one of them with a “dusky phlegm-like substance spread throughout the clothing … from the inside, oozing slowly from every orifice.” Purer Lovecraft would hardly be possible.

The last story is called “The Ancient Tower” and is set in the Kham region of Greater Tibet. An anthropologist (again) becomes obsessed by an isolated tower, or stupa, on the banks of a lake. The locals tell him not to go near it because of spirits, but he opts to spend a night there (when don’t they in stories like these?). At first all appears ordinary enough, but what he eventually encounters shakes his sanity.

Crucial to this story are thoughts about things that might have happened before recorded history, before even the ancient pre-Buddhist Tibetan religion of Bon, secret cults that have been incompletely suppressed by the dominant religions. This kind of focus is common to many stories of this genre, both in Lovecraft and his imitators.

The four tales, incidentally, are linked by an original narrative, created for this book by Arthur Meursault and his fellow translator.

So who is Meursault — or Oobmab and Akira, come to that? All three seem to be pseudonyms. Akira is a Japanese cyberpunk manga series, and Oobmab a form of woven bamboo. We know more about Meursault, though. He’s the author of another Camphor title, Party Members. I reviewed this novel on March 2, 2017 and found it too vitriolic for my taste, but I’ve revised this opinion and now consider it a wide-ranging and important novel.

So now we have this talented writer having mastered Chinese and coming up with a sophisticated and stylish translation, not to mention an ingenious linking narrative. Whoever he is, Taiwan is lucky to have him, as is Camphor Press. These two books are among Camphor’s best, and The Flock of Ba-Hui is in addition something of a breakthrough and, one hopes, the beginning of an important and fascinating series. A triumph, in other words.

The Lee (李) family migrated to Taiwan in trickles many decades ago. Born in Myanmar, they are ethnically Chinese and their first language is Yunnanese, from China’s Yunnan Province. Today, they run a cozy little restaurant in Taipei’s student stomping ground, near National Taiwan University (NTU), serving up a daily pre-selected menu that pays homage to their blended Yunnan-Burmese heritage, where lemongrass and curry leaves sit beside century egg and pickled woodear mushrooms. Wu Yun (巫雲) is more akin to a family home that has set up tables and chairs and welcomed strangers to cozy up and share a meal

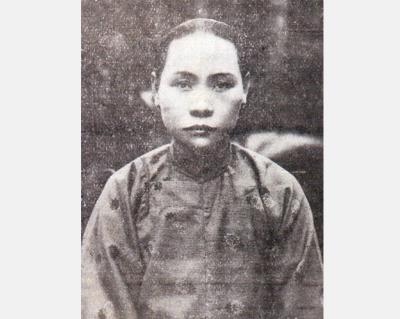

Dec. 8 to Dec. 14 Chang-Lee Te-ho (張李德和) had her father’s words etched into stone as her personal motto: “Even as a woman, you should master at least one art.” She went on to excel in seven — classical poetry, lyrical poetry, calligraphy, painting, music, chess and embroidery — and was also a respected educator, charity organizer and provincial assemblywoman. Among her many monikers was “Poetry Mother” (詩媽). While her father Lee Chao-yuan’s (李昭元) phrasing reflected the social norms of the 1890s, it was relatively progressive for the time. He personally taught Chang-Lee the Chinese classics until she entered public

Last week writer Wei Lingling (魏玲靈) unloaded a remarkably conventional pro-China column in the Wall Street Journal (“From Bush’s Rebuke to Trump’s Whisper: Navigating a Geopolitical Flashpoint,” Dec 2, 2025). Wei alleged that in a phone call, US President Donald Trump advised Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi not to provoke the People’s Republic of China (PRC) over Taiwan. Wei’s claim was categorically denied by Japanese government sources. Trump’s call to Takaichi, Wei said, was just like the moment in 2003 when former US president George Bush stood next to former Chinese premier Wen Jia-bao (溫家寶) and criticized former president Chen

President William Lai (賴清德) has proposed a NT$1.25 trillion (US$40 billion) special eight-year budget that intends to bolster Taiwan’s national defense, with a “T-Dome” plan to create “an unassailable Taiwan, safeguarded by innovation and technology” as its centerpiece. This is an interesting test for the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and how they handle it will likely provide some answers as to where the party currently stands. Naturally, the Lai administration and his Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) are for it, as are the Americans. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is not. The interests and agendas of those three are clear, but