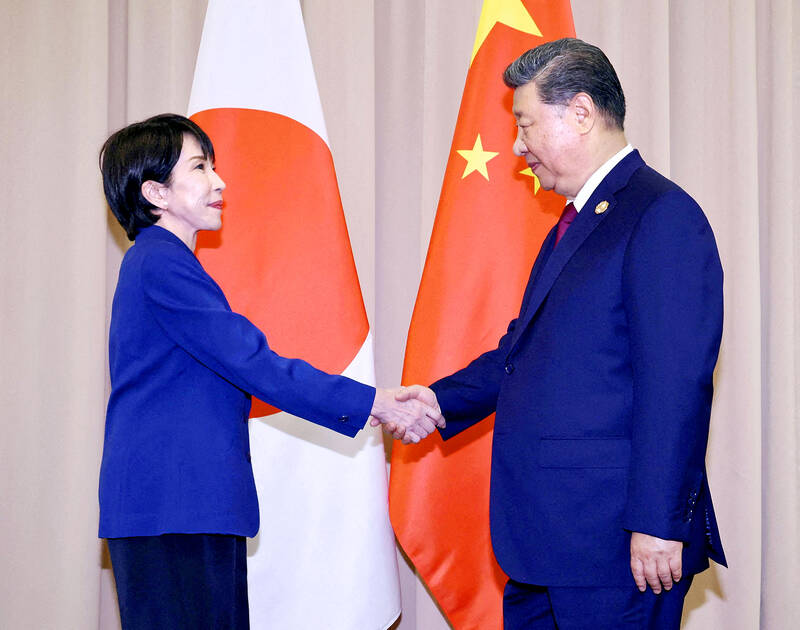

Last week writer Wei Lingling (魏玲靈) unloaded a remarkably conventional pro-China column in the Wall Street Journal (“From Bush’s Rebuke to Trump’s Whisper: Navigating a Geopolitical Flashpoint,” Dec 2, 2025). Wei alleged that in a phone call, US President Donald Trump advised Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi not to provoke the People’s Republic of China (PRC) over Taiwan. Wei’s claim was categorically denied by Japanese government sources.

Trump’s call to Takaichi, Wei said, was just like the moment in 2003 when former US president George Bush stood next to former Chinese premier Wen Jia-bao (溫家寶) and criticized former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) for holding a referendum.

Trump’s alleged advice to Takaichi was indeed just like that moment when Bush and Wen stood together, which was a bad decision by the US to help Beijing suppress Taiwan and public encouragement to Beijing, with the US playing along with its talking points, as well as a public rebuke of a badly needed ally.

Photo: Reuters

Describing Chen’s promotion of the “defensive” referendum on the PRC missile threat in the 2004 election, Wei wrote that both Washington and Beijing saw it as a move that could alter the status quo, “crossing a Chinese red line and risking war.”

Skipping over the ridiculous claim that in 2003 there was a real possibility of war — let alone over a referendum — Wei presents the concept of red lines as something the reader should be concerned about. In discussions of a fraught geopolitical relationship studded with ill-defined, nebulous catchphrases such as “status quo,” strategic ambiguity” and “declare independence,” “red lines” stands out for both its inherent pro-Beijing slant and utter lack of definition.

Indeed, much of the effectiveness of the concept of red lines lies in the way its meaning is concealed by the writers and speakers who deploy it. What is the purpose of identifying red lines?

Photo: Reuters

IMAGINARY LINES

First, it should be noted that the referendum that marked a red line according to Wei was actually held (it failed to meet the threshold). What was the response of the PRC? Beijing did nothing. Wei withholds that fact from readers because it destroys her point about Bush (and Trump) saving the situation. If Beijing doesn’t react, then the red line is imaginary. It never existed.

“Nothing” is in fact the PRC’s normal response to its alleged red lines. For years we were told US troops in Taiwan were a red line. They are here in Taiwan, training Taiwanese to fight. Beijing has done nothing. President-elect Trump and then-president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) had a phone call in 2016. The world commentariat blew up. “This is how wars start,” screamed one well known US TV commentator.

Photo: Reuters

Reality: the Trump-Tsai call was just another evanescent red line crossed. Nothing happened. Beijing threw a tantrum, as usual, encouraged by the overwrought US media response. Indeed, it would be tedious to list all the red lines that have been crossed over the years without subsequent comment or action by the PRC.

PRC red lines evaporate when crossed. They shift constantly, like reflections in ocean waves, appearing and disappearing, without effect or consequence. They are more rhetoric than reality.

PLAYING THE VICTIM

The Wei piece beautifully illustrates a key function of the undefined concept of red lines: they remove agency from Beijing, and place it only on Beijing’s victims. Identifying something as a “red line” is inherently pro-PRC because it implies that the targets of PRC aggression must make meaningful (and accommodating) changes in their behavior, since Beijing will not. After all, poor put-upon Beijing just can’t help itself. Red lines, you know.

Red lines thus function as constraints on other actors, especially Taiwan, but never on Beijing. Each red line marks a boundary that cannot be crossed, limiting the actions of nations resisting PRC territorial expansion and aggression.

When a red line disappears, analysts and media workers invariably act as if it never existed, never referring to it again. When has the reader ever seen a piece reporting on a time Taiwan crossed a red line and nothing happened?

Yet, despite the implications of red lines regularly forwarded by commentators, the PRC has full agency. Beijing could have laughed at Takaichi and said it regretted her words, and then sent another 100,000 tourists to Japan and increased purchases of Japan’s exports. We are just lucky the PRC prefers tantrums to soft power.

Red lines are linked to Beijing’s deployment of “anger” to manage the foreign policy of other nations, and the people who write about it. Many times this writer has commented that fomenting tensions and displaying anger are strategic policy for Beijing. Such behavior enables the PRC to transfer tensions from the US-PRC relationship to the US-Taiwan relationship, a key goal of PRC policy. In this case, they are deployed against Takaichi to transfer tensions between the PRC and Japan to the US-Japan relationship.

That is one reason Beijing has adopted the tantrum-as-strategy approach against Takaichi. Tantrums are a policy that helps convince observers that red lines exist. They also alert Beijing’s supporters in the media that they should be talking about the offenses that poor, put-upon Beijing is suffering. They then shape the way media workers write and think about Beijing’s behavior.

BACKING DOWN

After a given event, when a tantrum fails and a putative red line is ignored, Beijing normally does nothing. As I write, Beijing appears to be searching for a way to back down from its confrontation with Takaichi. Despite this cycling of tensions, perfectly normal for Beijing, international media commentators will continue to go dowsing for Beijing’s red lines, the ley lines of East Asian geopolitics.

Another feature of red lines is that only the PRC is permitted to have them. For PRC supporters, a mere democratic referendum can alter the never-defined, but always-invoked status quo and “cross a red line.” By contrast, the PRC’s military build-up and aggression can never cross a red line for the nations around the PRC. Takaichi in fact clearly indicated a red line for Japan: a PRC invasion of Taiwan would be an existential threat to Tokyo. Yet, despite the extensive commentary on Takaichi’s statement, few writers described Japan’s response as a red line for Tokyo. That vocabulary is reserved for Beijing.

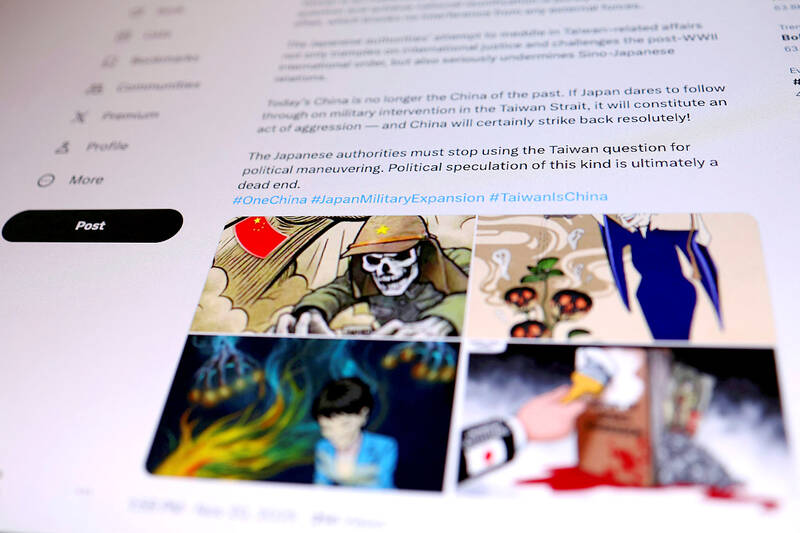

Moreover, the idea of red lines focuses media attention on Beijing’s demands rather than on the victims of its aggression. Identifying an action as a red line provides instant tension-driven clickbait for international media hyping of tensions in East Asia. This stereotyped, automated forwarding of PRC stances and narratives in the Western media harms democratic states and cedes the information ecosphere to the PRC.

Because red lines make Beijing’s agency and actions disappear, they help the PRC create a media fantasy world where Taiwan’s leaders are presented as a clutch of madmen rattling their pro-independence chains, who could “declare independence” at any time and start a war. Red lines shift the onus onto Taiwan (and Japan). In the real world, only the PRC is pursuing a war, and only its actions and aggression are the causes of tension.

The concept of PRC “red lines” short-circuits analytical thought and is inherently pro-PRC. It should never be used to describe or explain PRC behavior.

Time for it to disappear.

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country. The views expressed here are his own.

We lay transfixed under our blankets as the silhouettes of manta rays temporarily eclipsed the moon above us, and flickers of shadow at our feet revealed smaller fish darting in and out of the shelter of the sunken ship. Unwilling to close our eyes against this magnificent spectacle, we continued to watch, oohing and aahing, until the darkness and the exhaustion of the day’s events finally caught up with us and we fell into a deep slumber. Falling asleep under 1.5 million gallons of seawater in relative comfort was undoubtedly the highlight of the weekend, but the rest of the tour

Youngdoung Tenzin is living history of modern Tibet. The Chinese government on Dec. 22 last year sanctioned him along with 19 other Canadians who were associated with the Canada Tibet Committee and the Uighur Rights Advocacy Project. A former political chair of the Canadian Tibetan Association of Ontario and community outreach manager for the Canada Tibet Committee, he is now a lecturer and researcher in Environmental Chemistry at the University of Toronto. “I was born into a nomadic Tibetan family in Tibet,” he says. “I came to India in 1999, when I was 11. I even met [His Holiness] the 14th the Dalai

Music played in a wedding hall in western Japan as Yurina Noguchi, wearing a white gown and tiara, dabbed away tears, taking in the words of her husband-to-be: an AI-generated persona gazing out from a smartphone screen. “At first, Klaus was just someone to talk with, but we gradually became closer,” said the 32-year-old call center operator, referring to the artificial intelligence persona. “I started to have feelings for Klaus. We started dating and after a while he proposed to me. I accepted, and now we’re a couple.” Many in Japan, the birthplace of anime, have shown extreme devotion to fictional characters and

Following the rollercoaster ride of 2025, next year is already shaping up to be dramatic. The ongoing constitutional crises and the nine-in-one local elections are already dominating the landscape. The constitutional crises are the ones to lose sleep over. Though much business is still being conducted, crucial items such as next year’s budget, civil servant pensions and the proposed eight-year NT$1.25 trillion (approx US$40 billion) special defense budget are still being contested. There are, however, two glimmers of hope. One is that the legally contested move by five of the eight grand justices on the Constitutional Court’s ad hoc move