Dec. 8 to Dec. 14

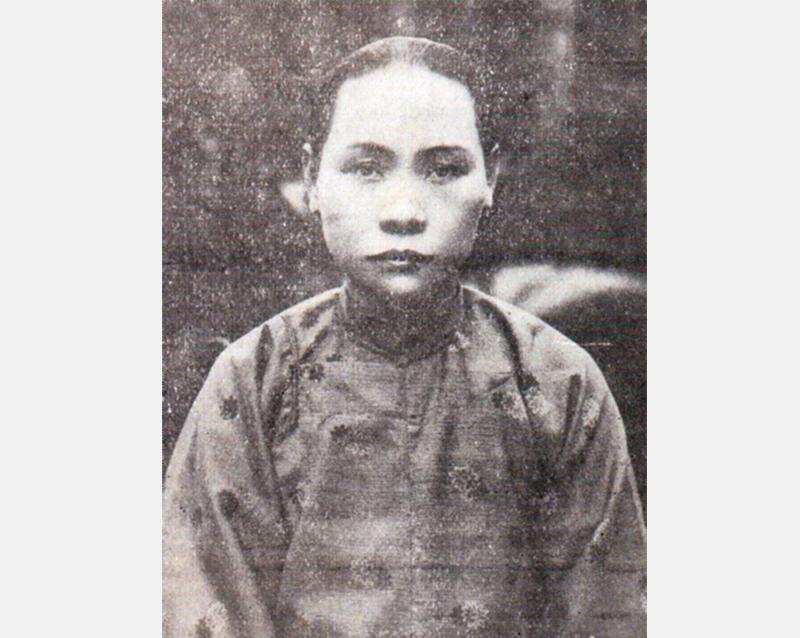

Chang-Lee Te-ho (張李德和) had her father’s words etched into stone as her personal motto: “Even as a woman, you should master at least one art.”

She went on to excel in seven — classical poetry, lyrical poetry, calligraphy, painting, music, chess and embroidery — and was also a respected educator, charity organizer and provincial assemblywoman. Among her many monikers was “Poetry Mother” (詩媽).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

While her father Lee Chao-yuan’s (李昭元) phrasing reflected the social norms of the 1890s, it was relatively progressive for the time. He personally taught Chang-Lee the Chinese classics until she entered public school at age 11.

Chang-Lee’s marriage into a prominent family at the age of 20 did not stifle her talent, as it did for the gifted poet Huang Chin-chuan (黃金川, see “Taiwan in Time: Bound talent: The lament of a female poet,” Nov. 2, 2025). Instead, the couple’s home became a gathering place for poets, writers and artists.

Chang-Lee offered the same support to her seven daughters. Before her eldest daughter left to study in Japan, she wrote: “Ride the wind with a resolve no less than any man’s, cut through the waves with the pride of a gifted woman. Your future is boundless, but carry yourself with dignity, so you may one day bring honor back to your hometown.”

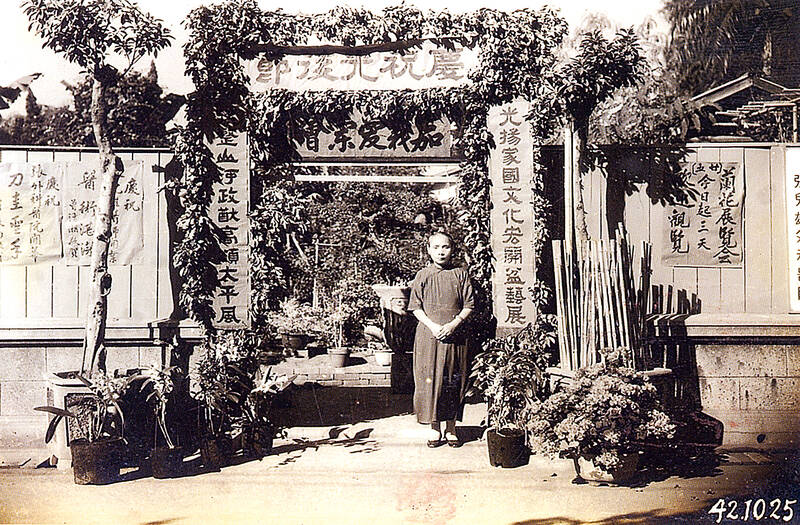

Photo courtesy of Chiayi City Cultural Affairs Bureau

EARLY EDUCATION

The Lee family rose to prominence during the 1800s in Siluo (西螺), Yunlin County, by helping the Qing Dynasty quell local unrest. Chang-Lee was born in 1893, and her father became an educator after the Japanese took over Taiwan in 1895.

Chang-Lee recalls that family gatherings often featured arts and culture: “Men and women, young and old, each practiced an art — from wooden clappers to bamboo strings. We playfully mimicked the movements as if we were part of a performance troupe.”

Photo courtesy of Chiayi City Cultural Affairs Bureau

An influential female figure was her father’s cousin Liu Huo-yuan (劉活源), who ran a private academy for relatives in her home — itself unusual for a woman at that time, writes Lee Hsin-hsin (李馨心) in “An exceptional woman across eras: A study of Chang-Lee Te-ho,” (跨時代的女性菁英: 張李德和研究). There, Chang-Lee studied classical literature, calligraphy and traditional morals.

At the age of 11, Chang-Lee entered Siluo Public School. Her class had 193 boys and just six girls, and Liu was also her teacher there. In 1907, she headed to Taipei to attend the Second Affiliated Girls’ School of the Governor-General’s Office, the only secondary education available for Taiwanese female students then. Out of the 41 students in her class, only seven graduated, Lee writes.

FOSTERING CULTURE

Photo courtesy of Chiayi City Cultural Affairs Bureau

The main purpose of secondary education for women at that time was to train them as public school teachers, as there was a shortage across Taiwan. Chang-Lee began her career in Douliu (斗六), Yunlin County, teaching there for two years before transferring back to her hometown.

She joined her first of many poetry associations at the age of 20. That same year, she married Chang Chin-tsan (張錦燦), the son of a prominent Chiayi family that also involved in the arts. It was a long-distance union at first, as she continued teaching in Siluo while he finished medical school in Taipei. Chang-Lee wrote poems expressing her longing during this period, and later transferred to Chiayi to care for her in-laws.

Her father-in-law was initially worried that her talents might get in the way of her domestic duties, but Chang-Lee proved she could balance both, demonstrating tact in handling family relationships. They exchanged poems, tended the garden and reportedly got along well.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Cultural Memory Bank

In 1914, Chang opened Zhufeng Clinic (諸峰醫院) in what is now Houbi District (後壁), Tainan. Chang-Lee quit teaching to help him run it, and in 1916 they moved back to Chiayi. In 1921, they built a new clinic and residence. They later expanded it with a classical Chinese garden called Yiyuan (逸園), and named the home Linlang Mountain Pavilion (琳瑯山閣), collecting stones and cultivating plants together. Their friends visited frequently, and ink and paper were always on hand for guests to paint or write calligraphy. In 1926, she started her own poetry association and frequently organized events.

When Huxian Preschool (壺仙幼稚園) opened in 1926, Chang-Lee served as director for five years and remained on the board for the rest of her life. In 1931, the clinic began offering midwife training. Chang-Lee helped out and taught the women Chinese, calligraphy, painting, self-cultivation and other topics.

Chang-Lee began studying contemporary painting under Lin Yu-shan (林玉山) in 1930, and just three years later she was selected for the prestigious Taiwan Art Exhibition. In 1939, both she and her daughter Chang Li-tzu (張麗子) were honored.

Photo courtesy of National Changhua Living Art Center

POST-WAR ENDEAVORS

The family changed their last name to Nagashima under the colonial government’s kominka assimilation policy. Chang-Lee’s eldest son Er-hsiung (張兒雄) joined the Japanese Army as a medic, and she went years without hearing from him, developing an eye condition as a result of her worry.

The Linglang Mountain Pavilion was destroyed during US bombings in 1945. The couple rebuilt it in the autumn of 1947, and once again it became a buzzing cultural gathering spot.

Chang-Lee became increasingly involved in public affairs, serving as chairwoman of the Chiayi Relief Association, which aided the needy, and on another charitable board. She earned widespread local respect for her work, and in 1951, she was elected to the provincial assembly, where she championed women’s education and welfare, abolishing the foster daughter system and comprehensive childcare facilities. She also advocated for gender equality in the workplace, increasing the female quota in the government and improving infrastructure and public health in Chiayi.

She remained dedicated to Taiwan’s poetry scene, serving as deputy chairwoman during the 1956 National Poet’s Gathering involving more than 80 associations. She left behind more than 1,000 poems. Beyond landscapes, family matters and personal reflections, many consisted of dedications to individuals or groups, as well as her concerns toward local affairs and public issues, writes Ou Tsung-chih (歐宗治) in “Preliminary explorations of Linlang Mountain Pavilion master Chang-Lee Te-ho’s Chinese poems” (琳瑯山閣主人張李德和漢詩初探). Many poems also show the family’s closeness to both Japanese and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) authorities, Ou added.

The couple lived at the pavilion until 1965, when they were compelled to sell it — along with many valuables — after their son-in-law’s coal business collapsed due to the advent of petroleum. They moved to Taipei to stay with their fifth daughter, and despite financial constraints, they remained culturally active.

In 1970, Chang died. Chang-Lee moved to Japan to stay with Er-hsiung, passing away two years later on Dec. 11, 1972.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not