Ai Weiwei Absent (艾未未‧缺席), the appropriately titled exhibition currently on view at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM), is the best show of the Chinese artist’s work you are likely see in Taipei for at least the next few years. Unfortunately, the displayed works reveal little about why he has become one of the world’s most important and respected artists.

The target of a renewed crackdown on dissent, Ai’s vocal critique of the Chinese Communist Party over the past few years has been met with surveillance, harassment, beatings, detentions and the destruction of his studio in Shanghai. Arrested in April on what human rights activists say were trumped up charges of tax evasion, he was released on bail in June, reportedly with the caveat that he doesn’t speak about his detention or leave Beijing. Hence the “absent” of TFAM’s title.

There is, however, a less noticeable but perhaps more sinister absence in this show. Ai’s social sculptures and virtual performance works, both of which seek to abolish the line separating his personal and public lives and engage the public in his work through social media (blogs, Twitter), are nowhere to be found.

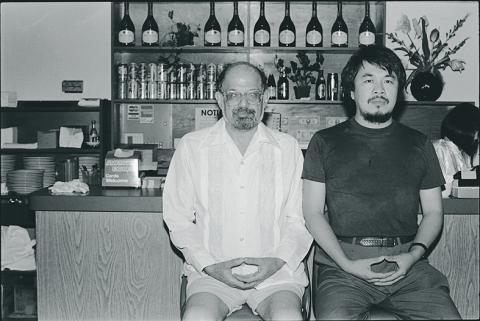

Photo courtesy of TFAM

It’s an interesting omission because these are the very projects that have gotten Ai in the most trouble with Chinese authorities. Oddly, staff at TFAM say that Ai chose the works on display himself, with the majority coming from his Beijing studio. Has an icon for the merging of art with activism, aesthetics and politics been muzzled? Almost certainly not. But if the TFAM show is anything to go by, he has been muted.

The retrospective covers photography from his early period in New York and Beijing’s East Village, as well as recent sculptures, installations and video work. Though there is no overriding theme, it does offer a worthwhile, albeit neutered, survey of his oeuvre.

The two sections on Ai’s photography — 100 photos, amounting to almost half the exhibition — deserve the closest scrutiny, because they foreshadow his later work.

Photo courtesy of TFAM

The 50 black-and-white images collected in Ai’s New York Period (紐約時期, 1983 to 1993), reveal the young artist to be an intrepid and sympathetic documenter of street scenes in the tradition of early Robert Frank. Images of homeless people living underground are placed alongside photos of protesters getting bashed around by police. Other photos draw attention to Ai’s early artistic influences. In one he stands beside a picture of Andy Warhol. Another shows him staring at a work by Marcel Duchamp, while a third depicts Ai’s Profile of Duchamp, Sunflower Seeds (1983), an early sculpture that is both a bow to the master of the readymade and a progenitor of Ai’s Sunflower Seeds (2010), a massive carpet of 100 million hand-painted porcelain sunflower seeds he created for Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in London.

Ai maintained his passion for documentation after he returned to Beijing in 1993, settling in what came to be known as Beijing East Village (北京東村), a collaborative of hard-hitting avant-garde performance artists, painters, sculptors and photographers that he records in the second series of photographs on display.

The community’s raucous atmosphere is aptly summarized by the photos Ai took of Zhang Huan’s 65 Kilograms, a performance art piece for which the artist strapped himself to a ceiling naked and bled onto a mattress below. It is perhaps inevitable that in the radical atmosphere of the collective’s performance art — Ma Liuming (馬六明) walking naked along the Great Wall or, later, Zhu Yu (朱昱) cooking and eating what he said was a human fetus — Ai developed an antagonistic and combative style.

Photo courtesy of TFAM

This is nicely expressed in Study of Perspective: Tiananmen Square (透視覺‧天安門), a largish photo of Ai giving the finger to Beijing’s iconic square. The photo was included in the Fuck Off (不合作的方式) exhibit he co-curated with art critic Feng Boyi (馮博一) in 2000, which was timed to coincide with (and give the figurative finger to) the state-sanctioned Shanghai Biennale. Police shut down the exhibition before its closing date.

It was at this time that Ai developed an interest in ancient Chinese art, as seen at TFAM with Coca-Cola Vase (可口可樂罐子, 2010), an urn emblazoned with the cola maker’s logo that echoes his Han Dynasty Urn With Coca-Cola Design (1994, not displayed), adding Chinese characteristics to Warhol’s pop aesthetic. The three-part photograph Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (失手, 1995) is both a statement about Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) destruction of artifacts and a suggestion that cultural renewal can only come through shattering outmoded ideas.

Helmet (安全帽, 2010), a marble sculpture of a safety helmet, suggests the perennial hazards at China’s worksites, as well as a head-bashing Ai received at the hands of police in Sichuan. Surveillance Camera (盟視攝像頭, 2010) reminds me of the Chinese Communist Party’s surveillance of its citizens.

Photo courtesy of TFAM

Yet none of the displayed works capture Ai’s current art practice. In an interview with the BBC, he said: “I don’t have this concept to separate my art from my daily life. I think they are one thing to me.”

It is for this reason that ArtReview magazine named Ai the most powerful person in the art world last month.

“Ai Weiwei’s number one ranking is the direct result of his efforts to expand the territory and audience for contemporary art practice by breaking down the barriers between art and life,” the magazine said.

Photo courtesy of TFAM

Indeed, from blogs inviting 1,001 Chinese citizens to participate in the 2007 Documenta 12 (an art fair in Kassel, Germany) to his 2008 Sichuan Earthquake Names Project (a blog that sought to collect the names of students killed in the earthquake), to the endless tweets about daily life in China that his followers can comment on, Ai has consistently sought to expand the borders of how we engage in and perceive art.

As ArtReview wrote: “Ai has promoted the notion that art’s real context is not simply ‘the market’ or ‘the institution,’ but what’s happening now, around us, in the real world.”

By its very title, Ai Weiwei Absent raises a profound question about how contemporary artists engage the public. In the end, however, the exhibit fails to adequately examine the parameters of the question it is asking.

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful