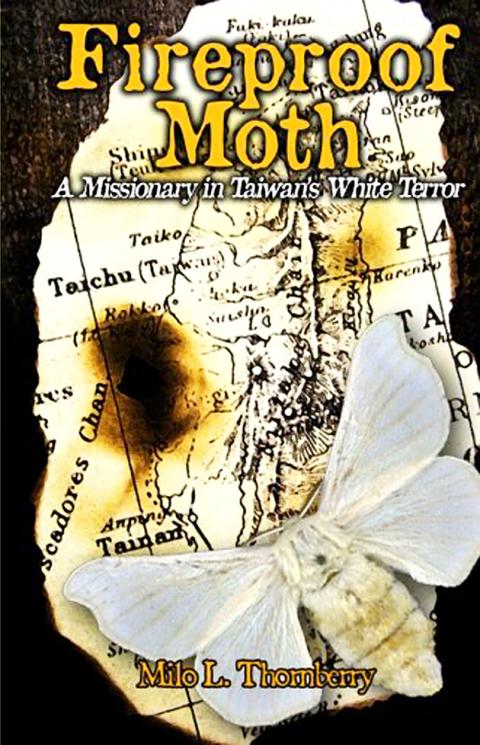

Fireproof Moth is an autobiographical account of a Methodist missionary’s stay in Taiwan in the late 1960s, but it reads like a thriller.

Author Milo L. Thornberry first describes his personal journey to becoming a minister in the mid 1950s. In 1965, the Methodist Church decided to send Thornberry and his wife Judith to Taiwan, and the couple went through preparatory sessions at Drew University and Stony Point Missionary Orientation Center north of New York. During this time he read some critical works such as George Kerr’s Formosa Betrayed and Mark Mancall’s Formosa Today.

Upon arrival in Taipei on New Year’s Eve 1966 the couple settled down, started language school, and gradually came to experience the suffocating hold that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) regime of Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) had on society in Taiwan. They also got to know Peng Ming-min (彭明敏), a professor who was under house arrest at the time for publishing a document titled A Manifesto for Self-Salvation in 1964.

The couple started to help channel support from overseas to families of political prisoners, with the help of Peng’s two courageous students, Hsieh Tsung-min (謝聰敏) and Wei Ting-chao (魏廷朝). They also began producing mimeographed information sheets to inform visiting friends and colleagues overseas about the repressive political atmosphere in the country.

Together with other foreign friends in Taiwan they approached American and European reporters and supplied background information on developments in Taiwan. Fox Butterfield of the New York Times and Selig Harrison of the Washington Post were among the reporters they communicated with.

When in September 1968 Peng told the couple that he had received indications from the Investigation Bureau of the Ministry of Justice, one of the main secret police organizations at the time, that he might have an “accident,” a plan was devised to smuggle him out of Taiwan. After more than a year of preparation the plan became a reality, and on Jan. 3, 1970, Peng left Taiwan using a doctored Japanese passport and disguised as a Japanese musician.

He made it safely to Sweden, where he received political asylum. Eventually Peng made it to the US, where he became a senior research scholar and visiting professor at the University of Michigan.

Oddly, the KMT authorities never discovered the role played by Thornberry and his wife in Peng’s escape. They surmised that he had been helped by the CIA. The matter even came up in the February 1972 discussions between then-US national security adviser Henry Kissinger and president Richard Nixon with Chinese premier Zhou Enlai (周恩來). Zhou accused the Americans of aiding Peng in his escape, but Nixon responded with indignation: “We had nothing to do with it.”

However, Taiwan’s secret police agencies kept an ever tightening watch over Milo and Judith, and on March 2, 1971 — more than a year after Peng’s escape — they were arrested and expelled from Taiwan. Selig Harrison visited them in their home while they were under house arrest and wrote a front-page article about it in the Washington Post (“Taiwan expels US missionary,” March 4, 1971).

It wasn’t until December 2003, at a reunion of human rights and democracy activists organized by the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy, that Milo and Judith — as well as the Japanese counterparts who also played a crucial role — disclosed their involvement in Peng’s escape.

The book reads like a spy thriller and fills a key void in the written history of Taiwan’s very recent transition to democracy. It is highly recommended.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name

There is no question that Tyrannosaurus rex got big. In fact, this fearsome dinosaur may have been Earth’s most massive land predator of all time. But the question of how quickly T. rex achieved its maximum size has been a matter of debate. A new study examining bone tissue microstructure in the leg bones of 17 fossil specimens concludes that Tyrannosaurus took about 40 years to reach its maximum size of roughly 8 tons, some 15 years more than previously estimated. As part of the study, the researchers identified previously unknown growth marks in these bones that could be seen only