In the five-story building that houses Wang Film Production (

Wang Film is behind many major animation productions such as Mulan, The Lion King, Tarzan, Lilo & Stitch and The Little Mermaid. But as an OEM contractor to Disney, its name is not listed among the credits.

Wang Film, set up 22 years ago by James Wang (

Many employees of Wang Film see the company as the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp (TSMC) of the animation field. Like TSMC, Wang Film has been quietly earning foreign exchange for Taiwan over the last two decades -- but as yet, it doesn't have its own brand.

A senior animation artist surnamed Ho recalls:

"I remember back in the 1980s, the animators' union in the US had a dispute with their employers. The dispute became a stalemate and lasted a long time. It was at this time that US firms decided to shift production to Taiwan. At that time we had 800 animation artists, and we were all excited and exhausted. Every night we stayed up late working. Mr. Wang would order late-night snacks for everyone -- there was food for so many people it took a truck to deliver. It was an unforgettable time."

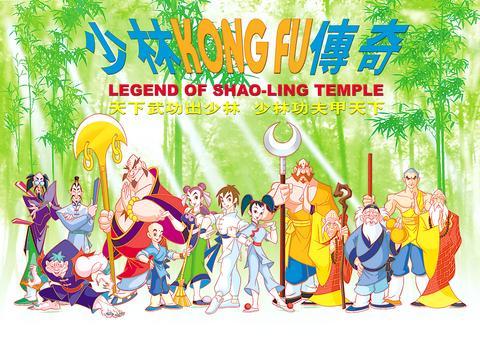

PHOTO COURTESY OF HONG YING UNIVERSE

It was a time when animation artists commanded high salaries, and, with all the overtime, they were able to take home NT$100,000 a month. These days, take-home pay is around NT$30,000 to NT$40,000 a month.

Although there is still plenty of work for Taiwan's animation artists, local firms working as an OEM manufacturer for the big US studios, see themselves as cut off from the big money.

To take the animation film The Lion King as an example, it is all too easy to see the unequal cut given to the manufacturer, as opposed to the copyright owner. The international box office for The Lion King was US$760 million, and the video revenue was US$780 million. Related merchandise rights were worth US$6 billion. In other words, The Lion King made Disney around US$7.5 billion, from which Wang Film, who did most of the production, was paid only US$67 million, just 0.9 percent of Disney's revenues from the film.

PHOTO COURTESY OF WANG FILM

Reflecting on this situation, James Wang said, "We've been carrying the sedan chair for others a long time now. It's time we set up our own brand." He said this during a meeting last year with premier Yu Shi-kun, who is behind an initiative to strengthen the animation industry in Taiwan.

Setting up their own brands has become a priority for many animation manufacturers in Taiwan. But this is not an easy task, for R&D is both capital and labor-intensive.

Hong Ying Universe (

Hsieh said the move to China was due to lower labor costs and the vast potential market.

"China's 380 million children have less money to spend on toys and entertainment than in many other parts of the world, but if this expenditure is brought up to the international average, US$34 a year, this would represent 30 percent of the world market," said Hsieh.

But can Taiwan take the lead in the China market? Both Wang and Hsieh agreed that there are problems. They pointed out that until the present time, Chinese cartoons have not produced a popular star like Donald Duck, Micky Mouse or Hello Kitty.

Hsieh of Hong Ying Universe sees the reason in the position that Taiwan still occupies in the production chain.

The production process of an animation film can be divided into pre-production, manufacturing and post-production. "What we've been doing is the middle part," she said. The characters have been designed, the shooting script has been written, and even the motion sequence has been roughly sketched out. "What we do is the composition, creating the backgrounds, making the animations [refining the motion] and articulating all these elements. Sometimes we do the rough cut. When all this is done, the product is sent back to the US for post-production, including dubbing, sound effects and visual effects.

"We are weakest in pre-production, designing characters and writing scripts for them," she said. This is a problem shared by Taiwan's conventional film industry. Wang Tung (

Within the animation industry, the problem is not confined to traditional animation -- painting on celluloid -- it also extends to computerized 3D animation.

Taiwan-based CG Computer Graphics (

It was not until last year that the company developed its own product with Master Q (

"For the character development and the script for the film, we need to rely on help from our partners in Japan and Europe," said Peggy Liou, marketing manager of CG.

So far, the biggest home-made animation project is Wang Film's Marco Polo, which is currently under development. The film is similar in scale to Disney's Mulan, with a budget estimated at US$40 million. "We will invest US$3 million purely in pre-production, developing the story and characters," said director Wang Tung. Although home grown, Wang Film plans to hire Tony Bancroft, director of Mulan and Toy Story 2 to direct the film.

Marco Polo, which takes place in China, is a clear attempt to cash in on the "Asian fever" of the last few years and it is hardly surprising that it has a very similar look to Mulan.

Still, local firms continue to seek a local style for future animations. Hong Ying Universe is currently involved on a project with the working title of The Legend of Panda (

Other projects include The Legend of Shaolin Temple, produced by Central Motion Picture Corp (CMPC) and manufactured by Hong Ying Universe, and The Monkey King (

Recently, the animation industry has also benefited from government support. Last year premier Yu Hsi-ku announced the expansion of subsidy and guidance programs for the digital content industry (ie software, animation and games industry), worth a total of NT$1.9 billion over the next six years.

As part of this move, the Industry Development Bureau of the Ministry of Economic Affairs (

"We appreciate the government's recognition of our efforts," said Wang Tung. "But we need more new talent. We need the kind of rapid policy-making and efficiency that has made Korea's software industry take off in the last three years," Wang said.

Facing strong competition from animation firms in the US and Japan, and the newly powerful Korea, Taiwan's animation firms recognize that they have a tough battle ahead.

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

We have reached the point where, on any given day, it has become shocking if nothing shocking is happening in the news. This is especially true of Taiwan, which is in the crosshairs of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), uniquely vulnerable to events happening in the US and Japan and where domestic politics has turned toxic and self-destructive. There are big forces at play far beyond our ability to control them. Feelings of helplessness are no joke and can lead to serious health issues. It should come as no surprise that a Strategic Market Research report is predicting a Compound