They walk the walk. They talk the talk. But they don't think the think. In the wake of the huge support given to US President George W. Bush two weeks ago, it's time we realized how different America's majority culture is, and changed our policies accordingly.

What Americans share with Europeans are not values, but institutions. The distinction is crucial. Like us, they have a separation of powers between executive and legislature, an independent judiciary, and the rule of law. But the American majority's social and moral values differ enormously from those which guide most Europeans.

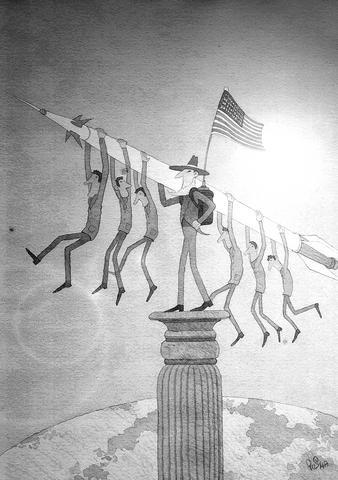

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

Its dangerous ignorance of the world, a mixture of intellectual isolationism and imperial intervention abroad, is equally alien. In the US more people have guns than have passports. Is there one European nation of which the same is true?

Of course, millions of US citizens do share "European" values. But to believe that this minority amounts to 48 percent and that America is deeply polarized is incorrect. It encourages the illusion that things may improve when Bush is gone. In fact, most voters for Senator John Kerry are as conservative as the Bush majority on the issues which worry Europeans. Kerry never came out for US even-handedness on the Israel- Palestine conflict, or for a withdrawal from Iraq.

Many commentators now argue for Europe to distance itself. But vague pleas for greater European coherence or for British Prime Minister Tony Blair to end his close links with the White House are not enough. The call should not be for "more" independence. Europe needs full independence.

We must go all the way, up to the termination of NATO. An alliance which should have wound up when the Soviet Union collapsed now serves almost entirely as a device for giving the US an unfair and unreciprocated droit de regard over European foreign policy.

As long as we are officially embedded as America's allies, the default option is that we have to support America and respect its "leadership." This makes it harder for European governments to break ranks, for fear of being attacked as disloyal. The default option should be that we, like they, have our interests. Sometimes they will coincide. Sometimes they will differ. But that is normal.

In other parts of the world, a handful of countries have bilateral defense treaties with the US. Some in Europe might want the same if NATO didn't exist. In contrast, a few members of the EU who chose to take the considerable risk of staying neutral during the cold war -- such as Austria, Finland, Ireland and Sweden -- see no need to join NATO in the much safer world we live in today.

So it makes no sense that the largest and most powerful European states, those who are most able to defend themselves, should cling to outdated anxiety and the notion that their ultimate security depends on the US. Do we really need American nuclear weapons to protect us against terrorists or so-called rogue states? The last time Europe was in dire straits, as Nazi tanks swept across the continent in 1939 and 1940, the US stayed on the sidelines until Pearl Harbor.

There is a school of thought which says that NATO is virtually defunct, so there is no need to worry about it. That view is sometimes heard even in Russia, where the so-called "realists" argue that Russia cannot oppose its old enemy, in spite of Washington's undisguised efforts to encircle it with bases in the Caucasus and central Asia. The more Moscow tries, they say, the more it seems to justify US claims that Russia is expansionist -- however odd that sounds, coming from a far more expansionist Washington.

It is true that NATO is unlikely ever again to function with the unanimity it showed during the cold war. The lesson from Iraq is that the alliance has become no more than a "coalition of the reluctant," with key members like France and Germany opting out of joint action.

But it is wrong to be complacent about NATO's alleged impotence or irrelevance. NATO gives the US a significant instrument for moral and political pressure. Europe is automatically expected to tag along in going to war, or in the post-conflict phase, as in Afghanistan or Iraq. Who knows whether Iran and Syria will come next? Bush has four more years in power and there is little likelihood that his successors in the White House will be any less interventionist.

NATO, in short, has become a threat to Europe. Its existence also acts as a continual drag on Europe's efforts to build its own security institutions. Certain member countries, particularly Britain, constantly look over their shoulders for fear of upsetting big brother. This has an inhibiting effect on every initiative.

France's more robust stance is pilloried by the Atlanticists as nostalgia for unilateral grandeur instead of being seen as part of France's pro-European search for a security project that will help us all.

Paradoxically, one argument for voting no in the referendum on the European constitution is based on this. Paul Quiles, a French socialist former defense minister, points out that Britain forced a change in the constitution's text so that Europe's common security policy, even as it tries to gather strength, is required to give primacy to NATO. Without control over its own defense, he argues, greater European integration makes little sense.

The immediate priority on the road to European independence is to abandon support for Bush's disastrous Iraq policy and get behind the majority of Iraqis who want the US to stop attacking their cities and leave the country. They feel US forces only provoke more insecurity and death.

Since Bush's victory two NATO members, Hungary and the Netherlands (which has a rightwing government), have said they will pull their troops out in March next year. Their moves show the falsity of the "old Europe, new Europe" split. In the post-communist countries, as much as in western Europe, majorities consistently opposed Bush's Iraq adventure, whatever their more timid governments said. Wanting to withdraw support for US foreign policy is not a left or right issue.

Ending NATO would not mean that Europe rejects good relations with the US. Nor does it rule out police and intelligence collaboration on issues of concern, such as the way to protect our countries against terrorism. Europe could still join the US in war, if there was an international consensus and the electorates of individual countries supported it.

But Europeans must reach their decisions from a position of genuine independence. The US has always based its approach to Europe on a calculation of interest rather than from sentimental motives.

Europe should do no less. We can and, for the most part, should be America's friends. Allies, no longer.

Jan. 1 marks a decade since China repealed its one-child policy. Just 10 days before, Peng Peiyun (彭珮雲), who long oversaw the often-brutal enforcement of China’s family-planning rules, died at the age of 96, having never been held accountable for her actions. Obituaries praised Peng for being “reform-minded,” even though, in practice, she only perpetuated an utterly inhumane policy, whose consequences have barely begun to materialize. It was Vice Premier Chen Muhua (陳慕華) who first proposed the one-child policy in 1979, with the endorsement of China’s then-top leaders, Chen Yun (陳雲) and Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平), as a means of avoiding the

The last foreign delegation Nicolas Maduro met before he went to bed Friday night (January 2) was led by China’s top Latin America diplomat. “I had a pleasant meeting with Qiu Xiaoqi (邱小琪), Special Envoy of President Xi Jinping (習近平),” Venezuela’s soon-to-be ex-president tweeted on Telegram, “and we reaffirmed our commitment to the strategic relationship that is progressing and strengthening in various areas for building a multipolar world of development and peace.” Judging by how minutely the Central Intelligence Agency was monitoring Maduro’s every move on Friday, President Trump himself was certainly aware of Maduro’s felicitations to his Chinese guest. Just

A recent piece of international news has drawn surprisingly little attention, yet it deserves far closer scrutiny. German industrial heavyweight Siemens Mobility has reportedly outmaneuvered long-entrenched Chinese competitors in Southeast Asian infrastructure to secure a strategic partnership with Vietnam’s largest private conglomerate, Vingroup. The agreement positions Siemens to participate in the construction of a high-speed rail link between Hanoi and Ha Long Bay. German media were blunt in their assessment: This was not merely a commercial win, but has symbolic significance in “reshaping geopolitical influence.” At first glance, this might look like a routine outcome of corporate bidding. However, placed in

China often describes itself as the natural leader of the global south: a power that respects sovereignty, rejects coercion and offers developing countries an alternative to Western pressure. For years, Venezuela was held up — implicitly and sometimes explicitly — as proof that this model worked. Today, Venezuela is exposing the limits of that claim. Beijing’s response to the latest crisis in Venezuela has been striking not only for its content, but for its tone. Chinese officials have abandoned their usual restrained diplomatic phrasing and adopted language that is unusually direct by Beijing’s standards. The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs described the