Oct. 27 to Nov. 2

Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire.

It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan Wen-yuan (潘文淵).

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Taiwan was at a crossroads then. Having withdrawn from the UN, its international standing was in decline, and the 1973 oil crisis had pushed the economy into a downturn. Lacking natural resources but with a dense, well-educated population, the government saw technological development as the key to future growth.

Premier Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國), who had just launched the Ten Major Construction Projects to modernize the nation’s infrastructure, asked Fei to come up with a critical technology initiative, writes Chang Ju-hsin (張如心) in Silicon Taiwan: The Legend of Taiwan’s Semiconductory Industry (矽說台灣:台灣半導體產業傳奇).

“The bigger the better,” Chiang reportedly said.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

This led to the breakfast shop meeting, where Pan proposed that they move from labor-intensive industries to tech-driven industries — namely integrated circuits (IC), which he believed would offer the greatest added-value for Taiwan’s electronics sector. Pan told Sun that the project would take four years and named the price. Sun, a staunch proponent of technological self reliance, nodded in approval.

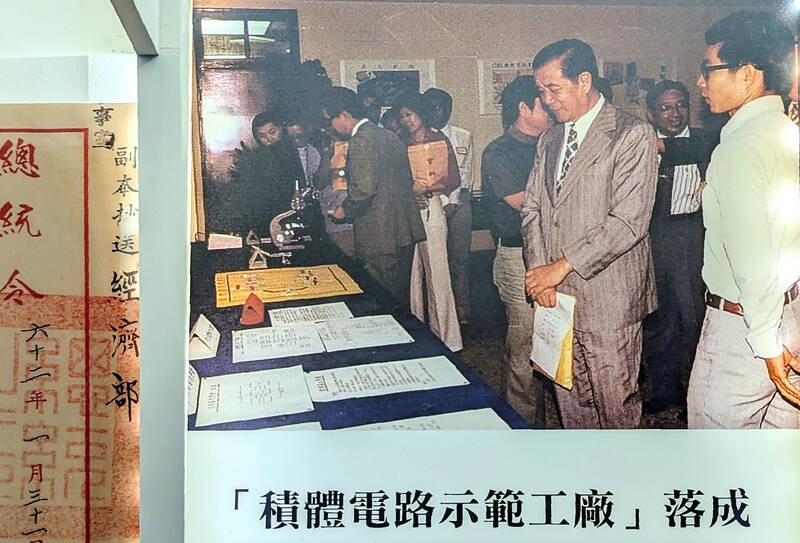

Pan then secluded himself in the Grand Hotel for 10 days to draft the proposal. Two years later, a contract was signed between ITRI and RCA to transfer IC technology to Taiwan, and 19 young engineers headed to the US to train. On Oct. 29, 1977, the nation’s first IC demonstration factory was inaugurated, producing three-inch silicon wafers — and history was born.

PATRIOTIC VISIONARY

Photo courtesy of Industrial Technology Research Institute

Most biographies note that Pan “never studied in Taiwan, never received a Taiwanese salary and never settled in Taiwan.” Born in Suzhou in 1912, Pan headed to the US to study electrical engineering in 1937. He opted to remain there after graduation, joining RCA where he spent most of his career.

In 1966, Fei recruited him to help launch the Modern Engineering and Technology Seminar, which aimed to bring the latest American technical expertise and industry trends to Taiwan’s engineers. In 1968, Pan began advising the Directorate General of Telecommunications.

Taiwan already had the capability to package ICs for foreign companies. But Pan realized that if Taiwan continued to rely on labor-intensive work, it would soon be replaced by Southeast Asia.

Photo courtesy of Industrial Technology Research Institute

His proposal to develop a homegrown IC industry was approved in August 1974. The following month he took early retirement from his post at RCA but refused any official position or salary from the government, only accepting travel and lodging expenses. Each year, he returned to Taiwan three times, staying for about two months on each visit.

Pan’s decision took a toll on his family finances, as his wife Shen Wen-tsan (沈文燦) also left her teaching job to accompany him. But Shen wrote in a 1978 article that it was Pan’s lifelong wish to do something for his motherland — which had become Taiwan due to the Chinese Civil War — before he grew too old.

“It was hard for me to agree with his passionate idealism at first, but after we had more discussions, I finally came to agree that the nation comes first, personal happiness second,” Shen wrote.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

STRONG OPPOSITION

The newly-formed, semi-official ITRI was chosen to oversee the project, carried out by the Electronics Research and Service Organization (ERSO). Pan established the Technology Advisory Council, a group of Chinese and Taiwanese-American scientists and engineers, to guide the technology transfer.

Researcher Huang Ling-ming (黃令名) writes in “A short history of semiconductor technology in Taiwan during the 1970s and the 1980s” that Pan hoped to use the technology to “produce specific IC products, rather than merely further scientific research.”

The team identified digital watches as a potential target, and focused on acquiring CMOS (Complementary Metal Oxide Semiconductor) technology. It was a relatively new technology, but it was adaptable, power efficient and suitable for a wide range of consumer electronics. The plan was a full transfer of manufacturing capabilities, including the construction of a demo factory capable of producing market-ready IC products for export.

This project faced strong opposition by both tech officials and overseas experts. Some argued it was too risky and challenging — even Western firms struggled with the technology — while others believed the government should prioritize fostering innovation over manufacturing and sales.

Chang writes that Sun ultimately decided to push the project through, sending Pan a Christmas card in 1975 that read: “Under the great help of you and your colleagues, this project will only succeed! There will inevitably be external resistance, but pay it no mind.”

AN INDUSTRY IS BORN

Pan convinced RCA to sell its outdated seven- micron CMOS technology to ITRI at a favorable price. In 1976, ITRI sent its first batch of 19 young engineers to the US for intensive training. According to ITRI records, they were divided into four teams, each heading to a different state to learn a specific aspect of IC development.

Many of these engineers would later become noted leaders in the semiconductor field, including Hu Ting-hua (胡定華), Shih Chin-tay (史欽泰) and Robert Tsao (曹興誠).

They returned home and helped set up the demo factory in Hsinchu County’s Zhudong Township (竹東). On inauguration day, Oct. 29, 1977, the plant forgot to let visitors wear protective clothing into the clean room. It took them two months to remove the resulting dust particles.

Within six months, however, it achieved a 70 percent yield rate — surpassing that of the original RCA plant.

The plant produced the first batch of made-in-Taiwan electronic watches the following year, transforming the nation into the world’s third-largest electronic watch exporter.

In 1980, ITRI spun off United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC) at the newly inaugurated Hsinchu Science Park, building a plant for the more advanced four-inch wafers. The government and state banks supplied much of the startup funds as few private investors were willing to join, but later they sold their shares, making UMC Taiwan’s first commercial semiconductor company.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name