Politics throughout most of the world are viewed through a left/right lens. People from outside Taiwan regularly try to understand politics here through that lens, especially those with strong personal identifications with the left or right in their home countries.

It is not helpful. It both misleads and distracts.

Taiwan’s politics needs to be understood on its own terms.

Photo: Chen Yi-kuan, Taipei Times

RISE OF THE DEVELOPMENTAL STATE

Arguably, both of the main parties originally leaned left-wing.

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) brought together radicals, dissidents and revolutionaries devoted to overthrowing their foreign Manchurian Qing overlords to establish a Chinese republic. Their leader, Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙), was within the context of the era left-wing, and the KMT organized itself along Leninist lines.

Photo: Liu Hsin-de, Taipei Times

They brought to Taiwan many of their social movements, and their socialist-leaning ideology easily absorbed the Japanese colonial state-run monopolies in key economic sectors. They ensured that the primary means of production were owned or controlled by the state, only liberalizing in the late twentieth century.

Even today, those state-owned enterprises remain major players in key industries like steel, petroleum, aviation, salt, telecommunications, fertilizer, alcohol and tobacco, though they no longer hold monopolies.

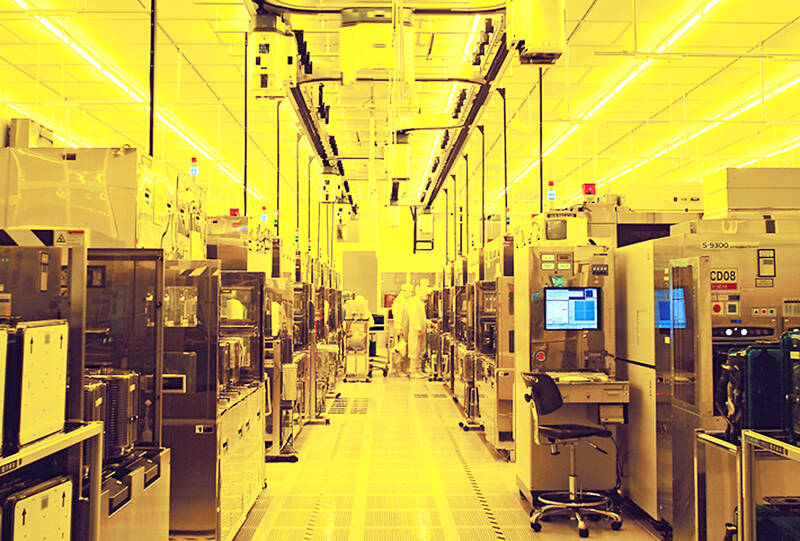

Much economic development is still directed and guided by the government, using financial infusions and laws to encourage favored industries, to a much higher degree than is the case in countries like the US. Some of their successes — like the science parks and investments that led to companies like Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) — are legendary, but their many failures are long forgotten.

Photo taken from Facebook

In the early years in Taiwan, the KMT was a left-wing dictatorship economically, and very corrupt. Labor unions, women’s groups and other nominally left-wing concepts were introduced, but were tightly controlled and loyal to the KMT. Welfare programs were set up, but only benefited those loyal to the regime.

Several factors saved Taiwan from turning into what Venezuela is today.

One factor was land reform. Having lost to the communists in China, and not beholden to landlords in Taiwan, they redistributed land to the peasants. This was popular, but also long-term meant that landholding was widespread, which as the economy boomed meant that many previously poor families became wealthy through their property and could invest on it — and have enough cash to bribe officials to ignore their labor safety and environmental lapses.

Many started factories, while others near cities made fortunes selling to developers, spreading capital more widely to an emerging class of Taiwanese entrepreneurs who would go on to fuel Taiwan’s economic miracle.

Another factor was the Americans. They provided significant development aid and a capitalistic ideology, both of which suited the government’s anti-Communist stance. American aid helped found some key industries, with the massive Formosa Plastics being a prime example. Japan’s booming economy also provided an influential model.

The KMT also invested heavily in educating their children, including sending many abroad, though native Taiwanese were usually blocked from the same opportunities until the 1980s. This investment gave the government a large pool of well-educated technocrats loyal to the KMT to draw on.

By the 1970s and 1980s, Taiwan was booming. This coincided with the rise of Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國), first as premier, then as president after his father’s passing.

Chiang was more practical and realistic than his father, and realized that “reclaiming the mainland” was a pipe dream. He saw that he needed more popular support, and where his father ruled with an iron fist, Chiang did the same, but disguised with a velvet glove and a softer touch.

He also invested heavily, including his famed Ten Major Construction Projects (十大建設) that laid out much of the critical infrastructure still used today. These included the Sun Yat-sen Freeway (National Freeway One), Chiang Kai-shek International Airport (renamed Taoyuan International Airport) and the ports in Taichung and Taoyuan.

He packed out the ministries in the Executive Yuan with technocrats. The older ones having fled China, while the younger ones were returning children of KMT families educated abroad.

THE DPP’S MODEL: THE KMT

The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was formed in this environment. Originally, they were a broad tent ideologically, but fundamentally, they all agreed on ending the KMT’s dictatorship and moving towards democracy.

Though I suspect that whoever came up with the English version of the party’s name was more left-wing and chose it hoping to suggest the party had “progressive” ideology, that is not what the name refers to. The name means progressing the cause of democracy, not a nod to the American progressive movement.

KMT president Lee Tung-hui’s (李登輝) shift to democracy in the early 1990s was very popular, and the KMT’s overseas education programs for their children gave them a solid base of educated, articulate and technocratic politicians with experience in democratic countries.

The KMT’s economic management was also popular and was widely credited for the booming economy.

Earlier, more idealistic efforts to promote more left-wing ideologies by the DPP soon fell by the wayside. They absorbed what was popular, including the KMT’s economic thinking, while campaigning on issues where the KMT was unpopular.

The DPP campaigned on democracy, fighting corruption and crime, and Taiwanese nationalism.

Aside from the Taiwanese nationalism, the KMT also ran on the same issues, often successfully. Over time, the issues the parties disagreed on polarized around issues of Chinese versus Taiwanese identity, sovereignty, defense and language, none of which are on the left-right spectrum.

The DPP absorbed much of what the KMT stood for, and even copied many of the examples set by the KMT as a party. Like the KMT, the party chair is a powerful position, and traditionally is the president or presidential candidate.

Regardless of which party is in power, the Executive Yuan largely writes the laws, rules and regulations — just as they did during Chiang Ching-kuo’s era. The center of power on most issues is not with the political parties, but with those technocratic bureaucrats.

This is why labor unions remain weak, the economy favors property developers and average wages remain lower than Japan’s and South Korea’s despite similar GDP per capita. Proposals to tackle these issues all come from inside the Executive Yuan, which is why they never change significantly.

WHATEVER WORKS ELECTORALLY

When the administration changes from one party to another, the policies of the previous administration are usually held over, though often tinkered with and re-branded to make it look like the new team is doing something different.

Both the major parties have championed issues traditionally considered left or right. Sometimes, the KMT and their allies took the lead on environmentalism, women’s rights and immigration; at other times, the DPP takes the lead.

Usually, it comes down to having a wedge issue for the opposition to leverage against the ruling party. It is easier for the opposition to pick up new ideas, and harder for the ruling party to act.

For example, recently the Constitutional Court ruled that the death penalty must be used more sparingly. Both parties are pro-death penalty, but the ruling party has to enforce the law, and the opposition used that to paint the ruling party as “soft on crime.”

The one social issue that some will suggest that the DPP is more left-leaning than the KMT is the fight over marriage equality. In this case, there is some evidence to back that and some hints of a more pronounced left/right split between the DPP and KMT since the late 2010s, but far less than people assume — which we will examine in an upcoming column.

While each party will adapt and adopt whatever left or right-wing issue that will benefit them electorally, it is on Taiwanese versus Chinese identity and nationalism where the two sides remain far apart.

And with China’s massive military buildup, those questions are increasingly existential.

Donovan’s Deep Dives is a regular column by Courtney Donovan Smith (石東文) who writes in-depth analysis on everything about Taiwan’s political scene and geopolitics. Donovan is also the central Taiwan correspondent at ICRT FM100 Radio News, co-publisher of Compass Magazine, co-founder Taiwan Report (report.tw) and former chair of the Taichung American Chamber of Commerce. Follow him on X: @donovan_smith.

It is a soulful folk song, filled with feeling and history: A love-stricken young man tells God about his hopes and dreams of happiness. Generations of Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang region, have played it at parties and weddings. But today, if they download it, play it or share it online, they risk ending up in prison. Besh pede, a popular Uighur folk ballad, is among dozens of Uighur-language songs that have been deemed “problematic” by Xinjiang authorities, according to a recording of a meeting held by police and other local officials in the historic city of Kashgar in

The Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS) told legislators last week that because the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) are continuing to block next year’s budget from passing, the nation could lose 1.5 percent of its GDP growth next year. According to the DGBAS report, officials presented to the legislature, the 2026 budget proposal includes NT$299.2 billion in funding for new projects and funding increases for various government functions. This funding only becomes available when the legislature approves it. The DGBAS estimates that every NT$10 billion in government money not spent shaves 0.05 percent off

Dec. 29 to Jan. 4 Like the Taoist Baode Temple (保德宮) featured in last week’s column, there’s little at first glance to suggest that Taipei’s Independence Presbyterian Church in Xinbeitou (自立長老會新北投教會) has Indigenous roots. One hint is a small sign on the facade reading “Ketagalan Presbyterian Mission Association” — Ketagalan being an collective term for the Pingpu (plains Indigenous) groups who once inhabited much of northern Taiwan. Inside, a display on the back wall introduces the congregation’s founder Pan Shui-tu (潘水土), a member of the Pingpu settlement of Kipatauw, and provides information about the Ketagalan and their early involvement with Christianity. Most

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) was out in force in the Taiwan Strait this week, threatening Taiwan with live-fire exercises, aircraft incursions and tedious claims to ownership. The reaction to the PRC’s blockade and decapitation strike exercises offer numerous lessons, if only we are willing to be taught. Reading the commentary on PRC behavior is like reading Bible interpretation across a range of Christian denominations: the text is recast to mean what the interpreter wants it to mean. Many PRC believers contended that the drills, obviously scheduled in advance, were aimed at the recent arms offer to Taiwan by the