NOV. 24 to NOV. 30

It wasn’t famine, disaster or war that drove the people of Soansai to flee their homeland, but a blanket-stealing demon.

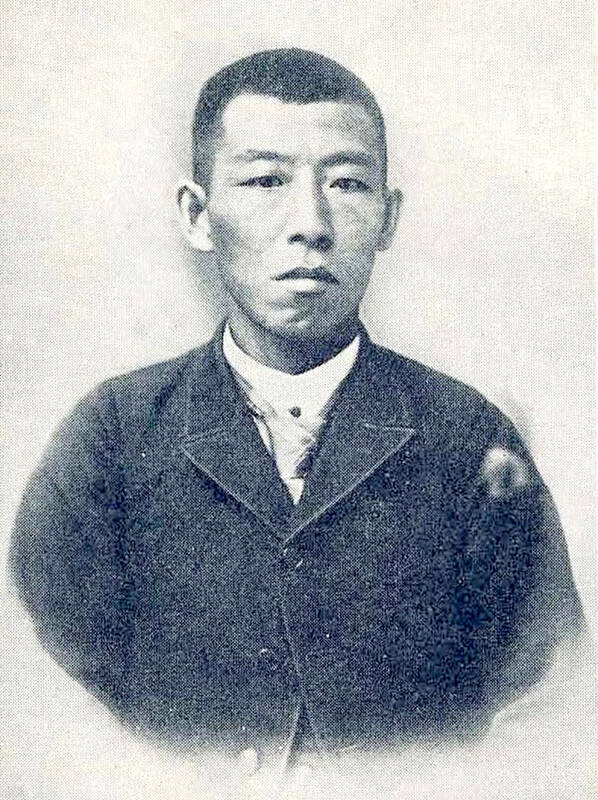

At least that’s how Poan Yu-pie (潘有秘), a resident of the Indigenous settlement of Kipatauw in what is today Taipei’s Beitou District (北投), told it to Japanese anthropologist Kanori Ino in 1897.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Cultural Memory Bank

Unable to sleep out of fear, the villagers built a raft large enough to fit everyone and set sail. They drifted for days before arriving at what is now Shenao Port (深奧) on Taiwan’s north coast, where they first settled before later dispersing.

Poan’s version appears to be the only recorded one involving a blanket-stealing monster, but Indigenous communities along the north and east coast down to Taitung share similar migration legends. Ino had initially come to Beitou to soak in the hot springs, which was a budding tourist area with the 1896 opening of the first inn, Tengu-an.

Last week’s feature detailed Kipatauw’s encounters with European colonizers, Qing authorities and Han settlers, starting with the Spanish in 1632. Like many other Pingpu (plains) Indigenous groups, the community gradually lost most of their land and fully adopted Han customs and language. Yet, as Ino observed, a “clear line of distinction” remained between them and their Han neighbors.

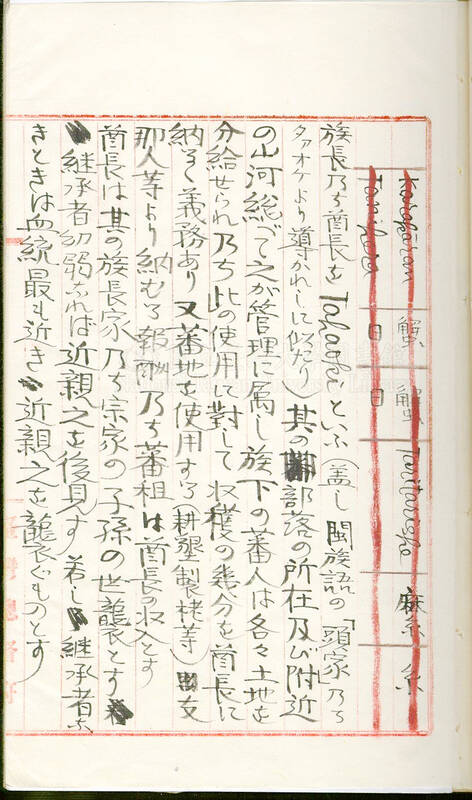

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Ino arrived in Taiwan with the colonial goal of “civilizing” the Indigenous through education, but his systematic studies — especially of the northern Pingpu — were the first of their kind, providing a foundation for future ethnographic studies.

COLONIAL MISSION

Born in 1867, Ino studied under Japan’s “father of anthropology,” Shogoro Tsuboi. Shortly after the Qing Empire ceded Taiwan to Japan, he applied to work in the new colony, arriving in November 1895.

Photo courtesy of National Taiwan University Department of Anthropology

Before departing for Taiwan, Ino wrote: “It is our duty to govern and civilize the [Indigenous peoples] … Education should be provided to enlighten them in knowledge and virtue, and they should be trained in productive skills. Therefore, one must first conduct detailed anthropological research … and then apply the results.”

There was still much unrest in Taiwan when Ino first arrived as locals continued to resist Japanese rule. He worked clerically for the Governor-General’s Office in Taipei, helping catalog Qing-era material on Indigenous peoples and studying Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), Atayal and Malay. He also cofounded the Anthropological Society of Taiwan.

By February 1896, things had calmed down in the Taipei area. Ino noted that the plains and hills south of Datun Mountain (大屯山) were once dotted with Indigenous settlements, but only two remained: Kipatauw and Kimassauw in today’s Shilin District (士林). Both were surrounded by Han villages.

Photo courtesy of National Taiwan University Library

Ino’s first destination was Kipatauw, 16km from Taipei, visiting on July 2 and 12. He noted that much of their traditional land had fallen into the hands of the Han settlers from Beitou.

Liang Ting-yu (梁廷毓) surmises in “History of Kipatauw: An examination and reflection on Indigenous–Han relations” (北投社史: 一個原、漢關係的考察與反思) that Ino likely visited Kipatauw’s upper settlement (頂社) in today’s Guizikeng (貴子坑) area, which preserved more of its strength presumably due to its mountainous location.

A FADING CULTURE

Ino detailed his early findings in a series of articles titled “Taiwan Correspondence,” published in the Journal of the Anthropological Society of Tokyo between 1896 and 1899.

In Kipatauw, Ino learned that out of the population of 117, only elders over 60 remembered past customs and fragments of the language. Poan was one of them, although in another version of the migration legend he said that his ancestors came from Shanxi (pronounced Soansai in Taiwanese) in China 200 years ago. Scholars such as Chan Su-chuan (詹素娟) attribute this to the effects of deep assimilation into Han culture.

Ino was greeted by 54-year-old village chief Lim O-pon (林烏凸), who paused his rice harvest work to guide him through the village. Each household welcomed him with tea and pastries. Most were Christians and attended the Beitou Presbyterian Church, established by Canadian missionary George Leslie Mackay in 1876. Ino noted that the dwellings, although similar to Han ones, were neater and cleaner.

Lim did not know much about their original traditions, but he claimed descent from the founders of Kipatauw. Ino recorded that Lim’s wife had deep eyes, high cheekbones and remembered much of their language, whereas younger generations appeared more Han. The couple presented him with an old wicker basket and a chest ornament made of beads and jade.

While the men braided their hair like the Han, women in Kipatauw still wore their hair the traditional way — parted in the front and wrapped with black cloth at the back. They did not bind their feet. By contrast, in Kimassauw, younger women wore Han-style hair and some practiced foot binding.

Older Kipatauw residents preserved many traditional clothes, weapons and household objects, and still knew their traditional names. Ino recorded a list of words, including numbers which he observed were similar to Malay.

ETHNIC CLASSIFICATION

Lim referred to himself as a “Pingpufan,” (平埔番) a Han term for the plains Indigenous. The character fan (番, or hoan in Taiwanese) implies that they were uncivilized or savage, and is considered derogatory today — but Ino observes other Pingpu communities using the word for themselves as well. The Japanese continued its usage, pronouncing it ban.

Ino quickly noticed that the Qing system for categorizing Taiwan’s Indigenous peoples into “cooked” (熟) and “raw” (生) based on their assimilation to Han culture and payment of taxes, was overly simplistic.

On May 23, 1897, the colonial authorities sent him on a 192-day expedition across Taiwan to produce a report guiding the government’s Indigenous educational policy. It was a perilous journey into uncharted land, probably the type of adventure he imagined when he left Japan.

He published the detailed Taiwan Indigenous Affairs, grouping the people he visited into eight categories corresponding to modern-day Atayal, Bunun, Tsou, Rukai, Paiwan, Puyuma, Amis and Pingpu. He further divided the Pingpu into 10 groups, with Kipatauw falling under the “Ketanganan,” living in 19 settlements stretching from northern Taoyuan to the northeast coast.

Ino was the first to use this term; previously the Pingpu were only referred to by individual settlement or geographical area. Although the accuracy of this classification is debated, the term (now commonly spelled Ketagalan) is still used today.

Ino hoped to continue studying Pingpu, but the opportunity never came. Considered “civilized” and administered the same as the Han, they also lost their rent-collecting privileges in 1905 — just another blow to Kipatauw, with much more upheaval in the decades to come.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Seven hundred job applications. One interview. Marco Mascaro arrived in Taiwan last year with a PhD in engineering physics and years of experience at a European research center. He thought his Gold Card would guarantee him a foothold in Taiwan’s job market. “It’s marketed as if Taiwan really needs you,” the 33-year-old Italian says. “The reality is that companies here don’t really need us.” The Employment Gold Card was designed to fix Taiwan’s labor shortage by offering foreign professionals a combined resident visa and open work permit valid for three years. But for many, like Mascaro, the welcome mat ends at the door. A

Last week gave us the droll little comedy of People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) consul general in Osaka posting a threat on X in response to Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi saying to the Diet that a Chinese attack on Taiwan may be an “existential threat” to Japan. That would allow Japanese Self Defence Forces to respond militarily. The PRC representative then said that if a “filthy neck sticks itself in uninvited, we will cut it off without a moment’s hesitation. Are you prepared for that?” This was widely, and probably deliberately, construed as a threat to behead Takaichi, though it

If China attacks, will Taiwanese be willing to fight? Analysts of certain types obsess over questions like this, especially military analysts and those with an ax to grind as to whether Taiwan is worth defending, or should be cut loose to appease Beijing. Fellow columnist Michael Turton in “Notes from Central Taiwan: Willing to fight for the homeland” (Nov. 6, page 12) provides a superb analysis of this topic, how it is used and manipulated to political ends and what the underlying data shows. The problem is that most analysis is centered around polling data, which as Turton observes, “many of these

Since Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) was elected Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair on Oct. 18, she has become a polarizing figure. Her supporters see her as a firebrand critic of the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), while others, including some in her own party, have charged that she is Chinese President Xi Jinping’s (習近平) preferred candidate and that her election was possibly supported by the Chinese Communist Party’s (CPP) unit for political warfare and international influence, the “united front.” Indeed, Xi quickly congratulated Cheng upon her election. The 55-year-old former lawmaker and ex-talk show host, who was sworn in on Nov.