When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct.

Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.”

As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders as a result of the summer’s havoc.

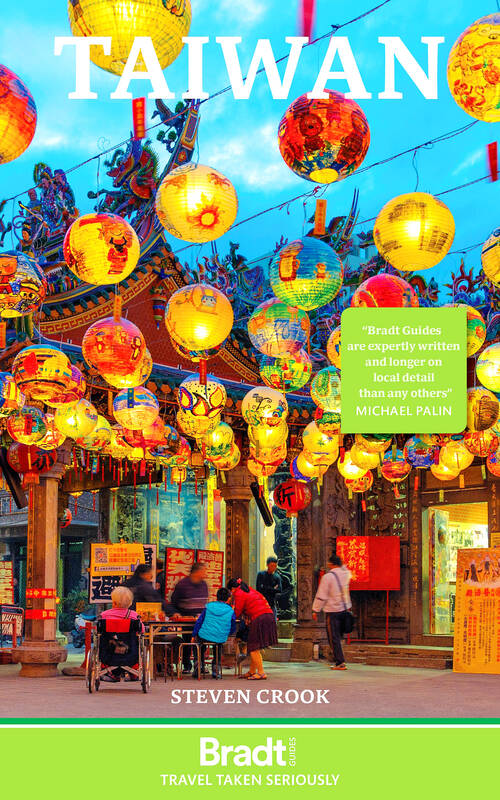

Photo: Steven Crook

When you write a guidebook, you have to accept that some of your work will immediately become obsolete. Where there are known unknowns, like the status of the trails and landmarks around Taroko Gorge (太魯閣), hedging language is a necessity.

There’s also the reality that you’re unlikely to make a lot of money. Despite that, when UK-based Bradt Guides (which calls itself “the world’s leading independent travel publisher”) approached me last year, I didn’t hesitate to say yes.

Since the third edition of my Taiwan guidebook appeared back in mid-2019, I’d been gathering snippets of information in the hope I’d get to do an update. (Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide came out at the start of 2011; the second edition reached bookstores in mid-2014.)

Photo: Steven Crook

I was thrilled to get the request, and also somewhat surprised. Since the end of the pandemic, Taiwan hasn’t exactly been inundated by foreign tourists. The picture looks a bit brighter now than it did at the start of this year, but 2025’s total isn’t likely to be much above 9.5 million, compared to 2019’s 11.86 million.

But that wasn’t the only reason. When I told an old acquaintance that I’d signed the updating contract, he was taken aback. “Next, I suppose, you’ll try to invent a better fax machine,” he quipped.

As far as many travelers are concerned, the kind of books that made Lonely Planet famous throughout the English-speaking world have gone the way of the fax machine. In this age of dynamic information resources like Google Maps, they do seem quaint. Guidebooks can’t tell you if a road like the Southern Cross-Island Highway is open today, and you can be sure much of the price information will be out of date. Even so, there’s still meaningful demand for them. Between now and the end of next year, Bradt plans to publish 45 titles, including brand-new guides to Afghanistan and Mauritania.

Photo courtesy of Bradt Guides

KEEPING THE FORMAT ALIVE

I make near-daily use of online travel information, and when going to unfamiliar places I don’t always carry a guidebook. But I don’t want them to disappear, so when I see tourists carrying old-school physical guidebooks, I try to find out why the format appeals to them, in the hope I’ll learn something that can be applied to my own book.

Some say they use guidebooks not so much for their hotel and restaurant listings as for the culture, fauna/flora and politics backgrounders. I like to think that, for most people visiting Taiwan, the history segment in my own book (from the island’s prehistory to the fizzle of this year’s recall campaign in just over 7,300 words) is both sufficient and engrossing.

An encouraging answer came from a thirty-something man toting The Rough Guide to Taiwan. He told me that just as he avoids overwhelming restaurant menus — preferring to walk out if there are 50-plus options — he doesn’t want to sift through blogs, social media posts, videos and official Web sites. He’d rather outsource that work.

Overhauling a guidebook is much easier than writing one from scratch, but a few numbers should give you an idea of how extensively I’ve revised mine. In terms of word count, it’s almost exactly the same — but 69 percent of the places to stay and 57 percent of the places to eat/drink didn’t appear in the previous edition. I’ve asked Bradt’s cartographer to make 489 changes to the book’s 32 maps.

Some of the businesses I’ve kept from previous editions have been rebranded under new ownership. One restaurant in the north hasn’t changed hands, yet the word “Beijing” is now conspicuously absent from its signage and menu. All the staff could tell me was that the boss decided to make this change a couple of years ago.

While updating the listings, I also noticed that many public facilities and private businesses now operate for fewer hours per week, compared to before the pandemic. I’d like to think this is because Taiwanese value their work-life balance more than they used to, but everyone tells me it’s actually a consequence of labor shortages. At the same time, it was interesting to note that high-speed train fares haven’t budged, and the cost of bus travel has hardly risen.

SOME IN, SOME OUT

At the outset, the publisher instructed me to make the fourth edition neither longer nor shorter than its predecessor (176,000 words, give or take). Adding 60-plus new attractions therefore meant excising some which appeared in the first, second and third editions.

My wife alerted me to Chan Jishan Xianfo Temple (禪機山仙佛寺) in Nantou County. I was hesitant to add yet another place of worship, but the Japanese character of this “forest shrine” is quite irresistible, and it makes for a good detour if driving from Taichung to Sun Moon Lake. Another excellent (and newly added) journey breaker is the very short trail up Dashibi Hill (大石鼻山), right beside the Hualien-Taitung coast road.

As for places good to visit when the weather is bad, the new edition includes the Railway Department Park (鐵道部園區) and Taiwan Hakka Museum (臺灣客家文化館). I wrote about the former for the March 19, 2021 issue of this newspaper (“A celebration of railway history in the heart of Taipei”). The latter is in Miaoli County’s Tongluo Township (銅鑼).

I hope every foreign visitor can see the country’s south and east, but I’m aware that many lack the time or inclination to travel far from Taipei. So I could expand coverage of Xinbeitou (新北投) and Tamsui (淡水), I dropped any mention of the excellent but inconveniently located museums at Academia Sinica.

One loyal reader insisted that I find space for the Jing-Mei White Terror Memorial Park (白色恐怖景美紀念園區). I did that, and also wrote a paragraph about the Taiwan New Cultural Movement Memorial Museum (臺灣新文化運動紀念館). The latter doesn’t make as deep an impression as the Jing-Mei site (or the National Human Rights Museum’s other outpost on Green Island) but if you’re walking from a metro station to Dihua Street (迪化街), you might as well take a look.

For a small number of timeless attractions, such as Longshan Temple (龍山寺) in Lukang (鹿港), it wasn’t necessary to change a single word when updating the guidebook. That’s more than can be said for the shrine’s Google Maps listing, which shows its name in Dutch (Lukang Drakenbergtempel) rather than English. This must have left a few tourists scratching their heads.

I’m not saying my book is going to be flawless. Defects will become obvious as soon as it hits the shelves in late spring, I’m sure. Fans of Taiwanese tea won’t find much in it. Readers will notice that I’m far more interested in architecture, industrial heritage, religious culture and trains than I am in oolong. Being a guidebook author is akin to being a museum curator: You’re selecting, rejecting and interpreting — and praying that others find the results fascinating.

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not