Microplastics have been found in the placentas of unborn babies, the depths of the Mariana Trench, the summit of Everest and the organs of Antarctic penguins. But how do they travel through the world, and what do they do to the creatures that carry them? Here is the story of how plastic contaminates entire ecosystems — and even the food we eat.

THE BEGINNING

The story starts with a single thread of polyester, dislodged from the weave of a cheap, pink acrylic jumper as it spins around a washing machine. This load of washing will shed hundreds of thousands of tiny plastic fragments and threads — up to 700,000 in this one washing machine cycle.

Photo: AFP

Along with billions of other microscopic, synthetic fibers, our thread travels through household wastewater pipes. Often, it ends up as sewage sludge, being spread on a farmer’s field to help crops grow. Sludge is used as organic fertilizer across the US and Europe, inadvertently turning the soil into a huge global reservoir of microplastics. One wastewater treatment plant in Wales found 1 percent of the weight of sewage sludge was plastic.

From here, it works its way up the food chain through insects, birds, mammals and even humans. Perhaps our jumper’s life as a garment will end soon, lasting only a few outings before it emerges from the wash shrunken and bobbling, to be discarded. But our thread’s life will be long. It might have only been part of a jumper for a few weeks, but it could voyage around the natural world for centuries.

INTO THE SOIL

Spread on the fields as water or sludge, our tiny fiber weaves its way into the fabric of soil ecosystems. A worm living under a wheat field burrows its way through the soil, mistaking the thread for a bit of old leaf or root. The worm consumes it — but cannot process it like ordinary organic matter.

The worm joins nearly one in three earthworms that contain plastic, according to a study published in April, as well as a quarter of slugs and snails that ingest plastic as they graze across soil. Caterpillars of peacock, powder blue and red admiral butterflies all contain plastic too, perhaps from feeding on leaves contaminated with it, research shows.

With the plastic in its gut, the burrowing earthworm will find it more difficult to digest nutrients, and is likely to start shedding weight. The damage might not be visible but for insects, eating plastic has been linked to stunted growth, reduced fertility and problems with the liver, kidney and stomach. Even some of the tiniest lifeforms in our soil, such as mites and nematodes — which help maintain the fertility of land — are negatively affected by plastic.

Plastic pollution in the marine environment has been widely documented, but a UN report found soil contains more microplastic pollution than the oceans. This matters not only for the health of soils, but because creepy crawlies such as beetles, slugs and snails form the building blocks of food chains. Our worm is now enabling this plastic fiber to become an international traveler.

UP THE FOOD CHAIN

In a suburban garden, a hedgehog snuffles through a dozen invertebrates in a night, consuming plastic fibers within them as it goes. One of them is our worm.

A study that looked at the feces of seven hedgehogs, found four of them contained plastics, one of which contained 12 fibers of polyester, some of which were pink. If hedgehogs don’t live in your country, substitute another small, scurrying mammal or bird: the same study found mice, voles and rats were also eating plastic, either directly or via contaminated prey.

Birds that eat insects such as swifts, thrushes and blackbirds are also ingesting plastic via their prey. A study earlier this year found for the first time that birds have microplastics in their lungs because they are inhaling them too. “Microplastics are now ubiquitous at every level of the food web,” says Prof Fiona Mathews, environmental biologist at the University of Sussex. The meat, milk and blood of farm animals also contain microplastics.

At the top of the food chain, humans consume at least 50,000 microplastic particles a year. They are in our food, water, and the air we breathe. Fragments of plastic have been found in blood, semen, lungs, breast milk, bone marrow, placenta, testicles and the brain.

INFILTRATING PLANTS

With the passage of time, our plastic thread has still not rotted, but has broken into fragments, leaving tiny pieces of itself in the air, water and soil. Over the course of years, it could become so small that it infiltrates the root cell wall of a plant as it sucks up nutrients from the soil. Nanoplastics have been found in the leaves and fruits of plants and, once inside, they can affect the plant’s ability to photosynthesize, research suggests. Here, inside the microscopic systems of the plant, the bits of our pink fiber cause all kinds of havoc — blocking nutrient and water channels, harming cells and releasing toxic chemicals. Staples such as wheat, rice and lettuce have been shown to contain plastic, which is one way they enter the human food chain.

TOO MUCH PLASTIC

Since the 1950s, humans have produced in excess of 8.3 billion tons of plastic — equivalent to the weight of one billion elephants. It finds its way into packaging, textiles, agricultural materials and consumer goods. Opting to live without it is almost impossible.

Fast fashion companies, drinks giants, supermarket chains and big agricultural companies have failed to take responsibility for the damage this has caused, says Emily Thrift, who researches plastic in the environment at the University of Sussex. She says individual consumers can reduce their consumption but should not feel that this is entirely their responsibility.

“If you do make this level of waste, there needs to be some form of penalization for doing it,” she says. “I truly believe until there is policy and ways to hold big corporations accountable, I don’t see it changing much.”

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

Last week the story of the giant illegal crater dug in Kaohsiung’s Meinong District (美濃) emerged into the public consciousness. The site was used for sand and gravel extraction, and then filled with construction waste. Locals referred to it sardonically as the “Meinong Grand Canyon,” according to media reports, because it was 2 hectares in length and 10 meters deep. The land involved included both state-owned and local farm land. Local media said that the site had generated NT$300 million in profits, against fines of a few million and the loss of some excavators. OFFICIAL CORRUPTION? The site had been seized

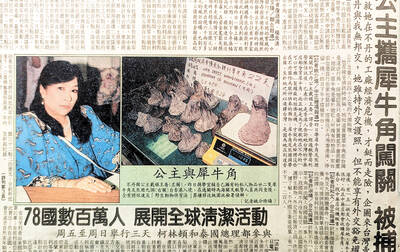

Sept. 15 to Sept. 21 A Bhutanese princess caught at Taoyuan Airport with 22 rhino horns — worth about NT$31 million today — might have been just another curious front-page story. But the Sept. 17, 1993 incident came at a sensitive moment. Taiwan, dubbed “Die-wan” by the British conservationist group Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), was under international fire for being a major hub for rhino horn. Just 10 days earlier, US secretary of the interior Bruce Babbitt had recommended sanctions against Taiwan for its “failure to end its participation in rhinoceros horn trade.” Even though Taiwan had restricted imports since 1985 and enacted

Enter the Dragon 13 will bring Taiwan’s first taste of Dirty Boxing Sunday at Taipei Gymnasium, one highlight of a mixed-rules card blending new formats with traditional MMA. The undercard starts at 10:30am, with the main card beginning at 4pm. Tickets are NT$1,200. Dirty Boxing is a US-born ruleset popularized by fighters Mike Perry and Jon Jones as an alternative to boxing. The format has gained traction overseas, with its inaugural championship streamed free to millions on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. Taiwan’s version allows punches and elbows with clinch striking, but bans kicks, knees and takedowns. The rules are stricter than the