Sept. 15 to Sept. 21

A Bhutanese princess caught at Taoyuan Airport with 22 rhino horns — worth about NT$31 million today — might have been just another curious front-page story.

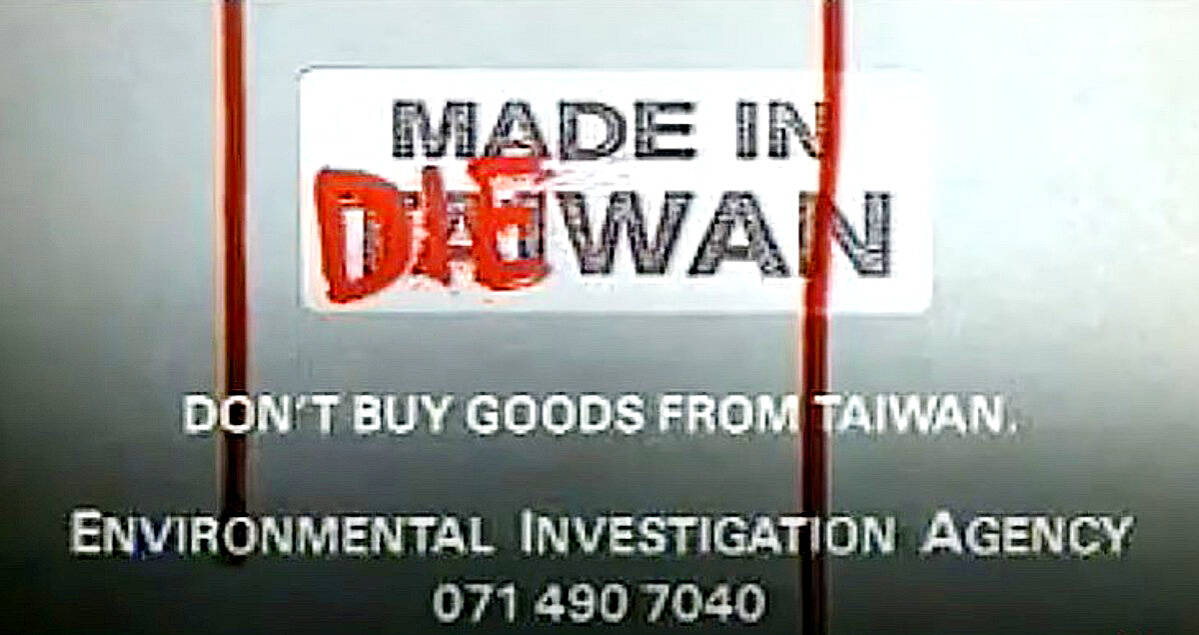

But the Sept. 17, 1993 incident came at a sensitive moment. Taiwan, dubbed “Die-wan” by the British conservationist group Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), was under international fire for being a major hub for rhino horn. Just 10 days earlier, US secretary of the interior Bruce Babbitt had recommended sanctions against Taiwan for its “failure to end its participation in rhinoceros horn trade.”

Photo: Screengrab

Even though Taiwan had restricted imports since 1985 and enacted the Wildlife Conservation Act in 1989, smuggling persisted. On Nov. 16, 1992, the EIA launched the infamous Die-wan ad, which opened with a “Made in Taiwan” TV displaying images of white rhinos. Blood starts spewing out of the vents, followed by gunshots and animal screams. “One country continues to trade in poached rhino horn,” the narrator stated, urging consumers to boycott Taiwanese goods.

While the government quickly prohibited the sale and use of rhino horn powder and added penalties, conservation groups pressed harder, and many Taiwanese felt the nation was unfairly singled out and the reports exaggerated.

Against this backdrop, the high profile arrest of Dekiy Wangchuck — with reportedly Taiwan’s largest ever rhino horn seizure — caused an international stir. As Taiwan and Bhutan did not have diplomatic relations, she had no immunity and was sentenced to 10 months in jail, a relatively harsh punishment.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

TRADITIONAL REMEDY

As Taiwan’s economy boomed in the 1970s, it became a major importer of rhino horn, valued in traditional medicine. The most coveted “fire horn” was obtained from the Asian rhino, which was the type Wangchuck carried. Due to the collapse in Asian rhino populations, most horns entering Taiwan were African, and by the time of her arrest, the Asian horn fetched about 16 times the price of African horn, according to a United Daily News report.

A 1994 Taiwan Today article states that during the 60s and 70s, rhino horn was a common item in family medicine cabinets. Most rural families had little access to Western-trained doctors, and rhino horn was effective in reducing high fever and bringing people out of a fever-induced coma.

Photo: Screengrab

“Twenty years ago, if a child had encephalitis — which is always accompanied by a high fever — the parents would ask for rhino horn,” the article stated.

At that time, rhino horn was still affordable. But prices shot up after the government restricted imports in 1985, leading to decline in popular usage. In 1986, officials stopped registering or renewing medicines containing rhino horn, and the 1989 Wildlife Conservation Act further tightened controls on rhino horn and ivory.

Many traditional pharmacies turned to accepted substitutes such as water buffalo horn, while younger generations gravitated toward Western medicine. But some doctors maintained that rhino horn was irreplaceable, as a 1991 article in Changchun (長春) magazine implored officials to allow limited usage for serious cases.

“Despite new laws and changing attitudes, there is no doubt that rhino horn is still being bought and sold,” the article stated. “Some people continue to believe that it contains some unknown, magic substance and that it can be taken, like vitamins, as a general health and energy booster,” wrote Taiwan Today.

The exorbitant prices smugglers and traditional pharmacies could fetch for rhino horn proved too tempting. As their value grew, wealthy people also collected them as status symbols. The prevailing attitude was that they didn’t kill the animals, so why were they to blame?

INTERNATIONAL PRESSURE

Trade in rhino horn was banned in 1976 under the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), but demand in Asia encouraged continued rampant poaching.

Scrutiny on Taiwan grew during the 1980s, and a 1989 report by rhino conservationist Esmond Bradley Martin called Taiwan “The greatest threat to the survival of Africa’s rhinos.”

In 1992, TRAFFIC International released a report titled “Horns of Dilemma: the Market for Rhino Horn in Taiwan,” which noted that rhino horn was still available in about two-thirds of surveyed pharmacies, and estimated that there was still between 3,863 and 9,321kg of horn stock in the nation — much higher than the government tally of 1,464kg. The report described Taiwan as a major transit hub, with Taiwanese traders shipping African horns via South Africa, then rerouting them to Hong Kong and China.

Although local experts disputed the numbers and methods, the report shocked international conservationists and placed Taiwan in the spotlight, writes Lee Pei-ying (李沛英) in “The Influence of the Pelly Amendment to Taiwan’s Conservation Policies” (美國培利修正案制裁對台灣保育政策的影響). Groups began calling for boycotts of Taiwanese products.

About a week after the Die-wan ad, the EIA held a scathing press conference in Taiwan, demanding stricter enforcement, collection and destruction of existing rhino horns, and compensation to source countries. Officials, environmentalists and traditional pharmacists balked at the accusations, arguing that the reports were exaggerated, biased and ignored Taiwan’s conservation progress. They maintained that much of what was sold as rhino horn was actually water buffalo horn, and that few could afford the real deal.

In February 1993, four US conservation groups urged the government and businesses to pressure Taiwan economically. Under the Pelly Amendment, the US could sanction countries that failed to enforce wildlife conservation regulations. While other nations had been threatened before, none were actually sanctioned.

In 1993, a US Fish and Wildlife Service investigation reported that Taiwan was the largest consumer nation of rhino horn and tiger bone, with rampant smuggling and weak enforcement. The other nations facing sanctions were China, South Korea and Yemen.

SANCTIONS HIT

Presumably, there was still a lucrative market in Taiwan for Wangchuck to take the risk. According to news reports, she had run into financial trouble, so she obtained seven rhino horns from the royal collection, purchased 15 more and headed to Hong Kong. While shopping for buyers there, a local businessman told her that the horns could fetch a much higher price in Taiwan.

Taiwan’s media praised the bust, with the United Daily News noting that it would greatly help reverse Taiwan’s reputation for leniency toward smuggling. Although Bhutan requested diplomatic immunity for Wangchuck, Taiwan declined.

By November 1993, only Taiwan faced sanctions. At a UN Environment Program meeting, officials acknowledged China and South Korea’s efforts, noting that while Taiwan had shown improvement, it was still lacking in enforcement. Then-US president Bill Clinton gave Taiwan four months to set up a wildlife protection agency, boost officer training and roll out a coordinated law enforcement and public education plan.

Despite progress, Taiwan was still sanctioned in April 1994 — the only nation ever punished under the Pelly Amendment. Effective that August, this covered wildlife imports including reptile leather goods, coral, shell and bone jewelry, aquarium fish and feathers. It cost Taiwan about NT$66 million per year, but more damage was done to its international reputation.

In response, Taiwan significantly increased its conservation resources and expanded its scope, and actively participated in international conservation programs. After eight months, the US deemed Taiwan to have met its requirements, and on Sept. 11, 1996, the sanctions were lifted.

Regardless of whether the sanctions were fair, Lin concludes that they had a significant impact on the development of Taiwan’s conservation system.

Unfortunately, smuggling persists. Just last August, a traditional medicine store was charged with selling NT$4.8 million worth of rhino horn to a cancer patient. The remedy did not work.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

As I finally slid into the warm embrace of the hot, clifftop pool, it was a serene moment of reflection. The sound of the river reflected off the cave walls, the white of our camping lights reflected off the dark, shimmering surface of the water, and I reflected on how fortunate I was to be here. After all, the beautiful walk through narrow canyons that had brought us here had been inaccessible for five years — and will be again soon. The day had started at the Huisun Forest Area (惠蓀林場), at the end of Nantou County Route 80, north and east

Specialty sandwiches loaded with the contents of an entire charcuterie board, overflowing with sauces, creams and all manner of creative add-ons, is perhaps one of the biggest global food trends of this year. From London to New York, lines form down the block for mortadella, burrata, pistachio and more stuffed between slices of fresh sourdough, rye or focaccia. To try the trend in Taipei, Munchies Mafia is for sure the spot — could this be the best sandwich in town? Carlos from Spain and Sergio from Mexico opened this spot just seven months ago. The two met working in the