It took years for Zehra Murguz to be able to testify about what happened to her and other Muslim women in the “rape camps” run by Serb forces during the war in Bosnia.

One of the awful memories that drove her to give evidence was of seeing a girl of 12 “with a doll in her arms” dragged into one of them.

Murguz felt she was also speaking “in the name of all the others, of that girl of 12 who will never talk... who was never found.”

Photo: AFP

The horror began for her in the summer of 1992 when Serb forces took the mountain town of Foca and Murguz was taken to the Partizan gym, one of several notorious rape camps the Serbs ran.

For months, dozens of Muslim women and girls were gang raped and forced into sexual slavery there. Others were sold or killed.

At least 20,000 people suffered sexual violence across Bosnia as Yugoslavia collapsed into the worst war Europe had then seen since 1945.

Photo: AFP

Most victims were Bosnian Muslims, but Serbs and Croat women also suffered.

In 2001, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia became the first court in Europe to recognize rape as a crime against humanity in a historic verdict against three Bosnian Serb army officers from Foca.

While a handful of survivors driven by a thirst for justice continue to collect thousands of testimonies, many remain locked in silence more than three decades on.

TRIPLE MURDER AND RAPE

Murguz, 61, began her judicial journey when she returned to Bosnia in 2011 — after years living in exile in Montenegro, Serbia and Croatia — to bring her neighbor to book for raping her during the war.

“If I don’t speak, it will be as if the crime never happened,” she told herself. He was still living in Foca and “wasn’t hiding,” she said.

He was arrested and tried in the local court in 2012. Going there was “like going back to 1992,” to the “agony” of that time, Murguz said. “I came face to face with him, we looked each other in the eye, and justice won out,” she said.

The man was jailed for 14 years, a “light sentence,” said Murguz “for the murder of three people and a rape.”

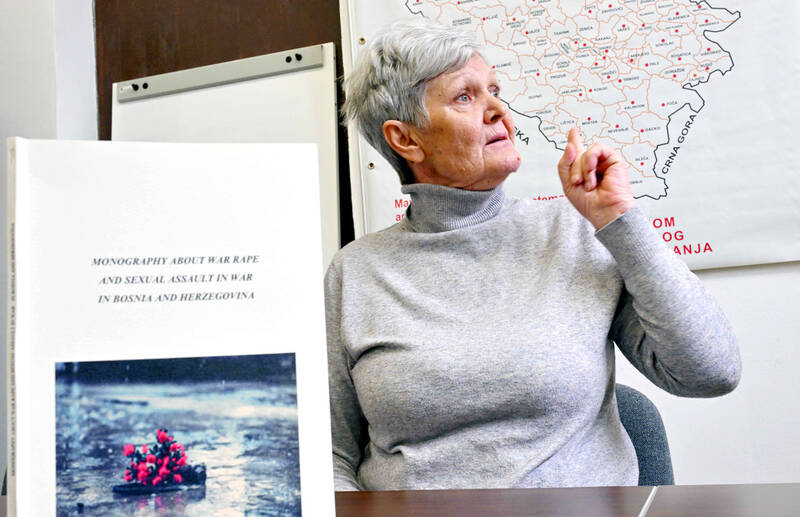

But the conviction at last “stamped him with his true identity — war criminal,” she said, sitting in a sewing workshop in Sarajevo run by the Victims of the War Foca 1992-1995 group.

Around her, other survivors wove fabric together, a form of collective therapy.

“To this day, only 18 verdicts have been delivered for crimes of sexual violence committed in Foca,” the group’s president, Midheta Kaloper, 52, said.

“Three trials are ongoing. A lot of time has passed, and witnesses are exhausted.”

She herself was a victim of “an unspeakable, inexplicable crime” in Gorazde, the “worst torture a girl can endure,” she said.

She still hopes the suspect will be tried in Bosnia, not in Serbia where he now lives.

But Kaloper warned that things have “stagnated” over the last five years, with 258 cases involving 2,046 suspects still needing to be judged, according to figures from the High Council of Magistrates.

Bosnian judges had tried 773 war crime cases by the end of last year — over a quarter involving sexual violence — according to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) monitoring mission.

It said there had been “significant delays” in hundreds of others where the suspects have yet to be identified.

“What kills us most is the excessive length of these proceedings,” said Kaloper.

TIMEBOMB

“We have been fighting for 30 years, and our only real success has been obtaining the law on civilian war victims,” under which survivors can be given a pension worth about US$400 a month, she said.

However, the law only covers the Muslim-Croat half of Bosnia and those living there, and not those living in the self-governing Serb Republika Srpska (RS) and the small mixed Brcko District in the northeast, which have different judicial systems.

Around 1,000 survivors have obtained war victim status in the Muslim-Croat federation and some 100 more in the RS and Brcko, said Ajna Mahmic, of the Swiss legal NGO Trial International. Rape, she said, still carries a particular stigma. “Unfortunately, as a society we still put the blame and shame on the victims rather than the perpetrators.

“Many of the survivors do not feel secure... some of the perpetrators are still living freely and some are working in public institutions,” some in positions of authority.

Not to mention the continued glorification “of war criminals [in the Balkans] and the minimization of the suffering we have endured,” Kaloper added.

Nearly half of ongoing cases are held up because the accused are abroad, an OSCE report said in January.

Another “worrying trend is the widespread failure of courts to grant victims compensation” in criminal cases, the OSCE added.

While witnesses could testify anonymously in The Hague, there is nothing to protect their identity in civil compensation proceedings in Bosnia.

“Even today it is very difficult for victims to speak,” said Bakira Hasecic, 71, head of the Women Victims of War group, and they keep the “weight of this tragedy in their hearts.”

Many follow what their former torturers are up to on social networks.

It is an emotional “timebomb that can explode at any moment and drives some to call us,” she said.

Though over 30 years have passed, 15 more victims stepped forward needing to talk in the last few months alone, Hasecic said.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)

Today Taiwanese accept as legitimate government control of many aspects of land use. That legitimacy hides in plain sight the way the system of authoritarian land grabs that favored big firms in the developmentalist era has given way to a government land grab system that favors big developers in the modern democratic era. Articles 142 and 143 of the Republic of China (ROC) Constitution form the basis of that control. They incorporate the thinking of Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙) in considering the problems of land in China. Article 143 states: “All land within the territory of the Republic of China shall