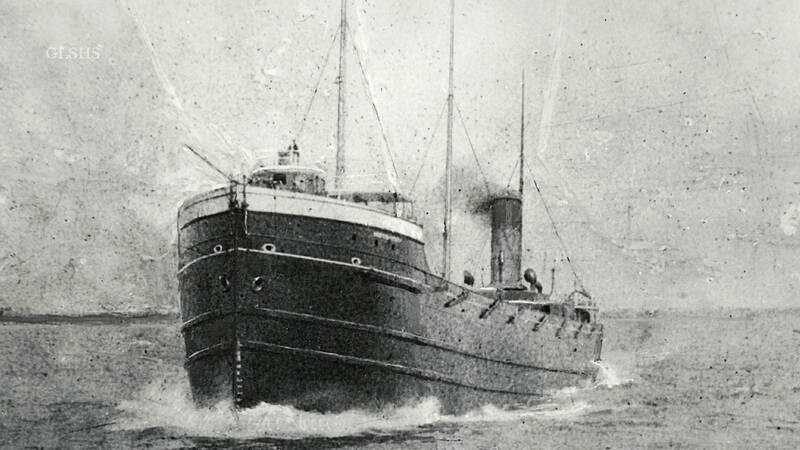

Twenty years before the Titanic changed maritime history, another ship touted as the next great technological feat set sail on the Great Lakes.

The Western Reserve was one of the first all-steel cargo ships to traverse the lakes. Built to break speed records, the 91.4-meter freighter dubbed “the inland greyhound” by newspapers was supposed to be one of the safest ships afloat. Owner Peter Minch was so proud of her that he brought his wife and young children aboard for a summer joyride in August 1892.

As the ship entered Lake Superior’s Whitefish Bay between Michigan and Canada on Aug. 30, a gale came up. With no cargo aboard, the ship was floating high in the water. The storm battered it until it cracked in half. Twenty-seven people perished, including the Minch family. The only survivor was wheelsman Harry W. Stewart, who swam 1.6 kilometers to shore after his lifeboat capsized.

Photo: AP

For almost 132 years the lake hid the wreckage. In July, explorers from the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society pinpointed the Western Reserve off Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The society announced the discovery Saturday at the annual Ghost Ships Festival in Manitowoc, Wisconsin.

“There’s a number of concurrent stories that make this important,” the society’s executive director, Bruce Lynn, said in a telephone interview. “Most ships were still wooden. It was a technologically advanced ship. They were kind of a famous family at the time. You have this new ship, considered one of the safest on the lake, new tech, a big, big ship. (The discovery) is another way for us to keep this history alive.”

TWO-YEAR SEARCH

Photo: AP

Darryl Ertel, the society’s marine operations director, and his brother, Dan Ertel, spent more than two years looking for the Western Reserve. On July 22 they set out on the David Boyd, the society’s research vessel. Heavy ship traffic that day forced them to alter their course, though, and search an area adjacent to their original search grid, Lynn said.

The brothers towed a side-scanning sonar array behind their ship. Side sonar scans starboard and port, providing a more expansive picture of the bottom than sonar mounted beneath a ship. About 97 kilometers northwest of Whitefish Point on the Upper Peninsula, they picked up a line with a shadow behind it in 182 meters of water. They dialed up the resolution and spotted a large ship broken in two with the bow resting on the stern.

CONFIRMATION DAY

Eight days later, the brothers returned to the site along with Lynn and other researchers. They deployed a submersible drone that returned clear images of a portside running light that matched a Western Reserve’s starboard running light that had washed ashore in Canada after the ship went down. That light was the only artifact recovered from the ship.

“That was confirmation day,” said Lynn, the society’s executive director.

Darryl Ertel said that discovery gave him chills — and not in a good way. “Knowing how the 300-foot Western Reserve was caught in a storm this far from shore made a uneasy feeling in the back of my neck,” he said in a society news release. “A squall can come up unexpectedly…anywhere, and anytime.”

Lynn said that the ship was “pretty torn up” but the wreckage appeared well-preserved in the frigid fresh water.

DANGEROUS GREAT LAKES

The Great Lakes have claimed thousands of ships since the 1700s. Perhaps the most famous is the Edmund Fitzgerald, an ore carrier that got caught in a storm in November 1975 and went down off Whitefish Point within 100 miles of the Western Reserve. All hands were killed. The incident was immortalized in the Gordon Lightfoot song, “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.”Assistant Wisconsin State Climatologist Ed Hopkins said that storm season on the lakes begins in November, when warm water meets cold air and winds blow unimpeded across open water, generating waves as high as 9.1 meters. The lakes at that time can be more dangerous than the oceans because they’re smaller, making it harder for ships to out-maneuver the storms, he said.

Brittle steel may have played a role in sinking

But it’s rare to see such gales form in August, Hopkins said. A National Weather Service report called the storm that sank the Western Reserve a “relatively minor gale,” he noted.

A Wisconsin Marine Historical Society summary of the Western Reserve sinking noted that the maritime steel age had just begun and the Western Reserve’s hull might have been weak and couldn’t handle the bending and twisting in the storm. The steel also becomes brittle in low temperatures like those of Great Lakes waters. The average water temperature in Lake Superior in late August is about 16 degrees Celsius, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The summary notes the Titanic used the same type of steel as the Western Reserve and that it may have played a role in speeding up the luxury liner’s sinking.

Seven hundred job applications. One interview. Marco Mascaro arrived in Taiwan last year with a PhD in engineering physics and years of experience at a European research center. He thought his Gold Card would guarantee him a foothold in Taiwan’s job market. “It’s marketed as if Taiwan really needs you,” the 33-year-old Italian says. “The reality is that companies here don’t really need us.” The Employment Gold Card was designed to fix Taiwan’s labor shortage by offering foreign professionals a combined resident visa and open work permit valid for three years. But for many, like Mascaro, the welcome mat ends at the door. A

Last week gave us the droll little comedy of People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) consul general in Osaka posting a threat on X in response to Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi saying to the Diet that a Chinese attack on Taiwan may be an “existential threat” to Japan. That would allow Japanese Self Defence Forces to respond militarily. The PRC representative then said that if a “filthy neck sticks itself in uninvited, we will cut it off without a moment’s hesitation. Are you prepared for that?” This was widely, and probably deliberately, construed as a threat to behead Takaichi, though it

If China attacks, will Taiwanese be willing to fight? Analysts of certain types obsess over questions like this, especially military analysts and those with an ax to grind as to whether Taiwan is worth defending, or should be cut loose to appease Beijing. Fellow columnist Michael Turton in “Notes from Central Taiwan: Willing to fight for the homeland” (Nov. 6, page 12) provides a superb analysis of this topic, how it is used and manipulated to political ends and what the underlying data shows. The problem is that most analysis is centered around polling data, which as Turton observes, “many of these

Since Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) was elected Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair on Oct. 18, she has become a polarizing figure. Her supporters see her as a firebrand critic of the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), while others, including some in her own party, have charged that she is Chinese President Xi Jinping’s (習近平) preferred candidate and that her election was possibly supported by the Chinese Communist Party’s (CPP) unit for political warfare and international influence, the “united front.” Indeed, Xi quickly congratulated Cheng upon her election. The 55-year-old former lawmaker and ex-talk show host, who was sworn in on Nov.