June 19 to June 25

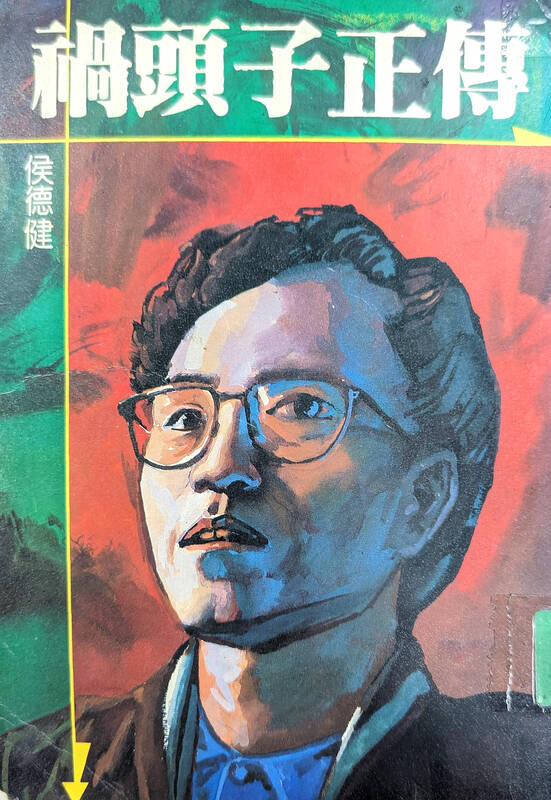

The nation was shocked when promising songwriter Hou Dejian (侯德健) illegally moved to Beijing in 1983. Hou was allegedly unhappy that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was trying to alter his lyrics and pressure him to write propaganda songs, but he writes in his autobiography, True Story of a Troublemaker (禍頭子正傳), that he really just wanted to see the place where his parents were born, and felt that he would find more creative inspiration there. His family, including his wife and young son, didn’t know about his plans.

“I felt like I couldn’t find satisfaction or surpass myself in Taiwan’s music scene,” he said in October 1988 during his first interview with the Taiwanese media since his departure. “I wanted to discover a new path.”

Photo courtesy of Taipei Public Library

Hou had his ups and downs in China, but he managed to release two acclaimed albums and was invited to perform in the 1989 CCTV New Year’s Gala. Things were finally looking up, he told the media.

But less than a year later, Hou found himself as one of the “Four Gentlemen (四君子) of Tiananmen Square” who led a hunger strike during the final days of the student demonstrations. He was eventually deported (or in his words, half-coerced and half-tricked by the authorities into smuggling himself) back to Taiwan.

His return on June 20, 1990, was just as unexpected as his departure. After paying a fine for illegal entry, he released his autobiography and an album before emigrating to New Zealand, saying that he felt unwelcome in Taiwan due to negative media attention.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Most Taiwanese are probably familiar with at least one of the few hits Hou penned before taking his talents to China, especially Any Empty Bottles for Sale? (酒矸倘賣無) sung by Su Rui (蘇芮).

ETERNAL GUEST

Hou grew up in a military dependents village in Kaohsiung’s Gangshan District (岡山) to parents from Sichuan and Hunan provinces. He writes that he felt like a guest no matter where he went.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute

“When people asked about my background, I always said I’m Sichuanese. But when they asked where my home was, I said without hesitation, Chiyuan Village (致遠) in Gangshan,” he writes, adding that he never felt any contradiction between the two.

Attending school with mostly Taiwanese kids, he writes that although there was discrimination, he mostly got along with them and was one of the few Mainlander students fluent in Hoklo (more commonly known as Taiwanese). But he felt deeply hurt during one incident while visiting a friend in Kaohsiung. After enjoying a fun afternoon in the fields, the conversation turned political — and his pal suddenly turned against Hou, calling him a “Mainlander pig” and telling his friends not to speak to him.

In China, however, Hou was still an outsider as a “Taiwanese compatriot,” and even at the Tiananmen Square protests, he recalls being ostracized by some. During the hunger strikes and negotiations with the military, Hou says he just did what he was told to do — as a guest, he did not feel the right to be too proactive and opinionated.

Hou was part of the “campus folk” movement of the 1970s, and the first song he sold, Catch the Loach (捉泥鰍), is still a children’s classic. The 1978 Descendents of the Dragon (龍的傳人), which expressed pride in being Chinese, was a huge hit in both Taiwan and later China. He wrote it in response to the US severing relations with Taiwan, and intended for it to lament the plight of the Chinese and express his hope for them to be strong again. It was one of the songs sung in unison during the Tiananmen Square demonstrations, and it gained newfound popularity when Wang Leehom (王力宏) covered it in 2000.

That song is not as popular today due to the shift in the political climate and rise in Taiwanese identity, but most people can probably recite the chorus to Any Empty Bottles for Sale?, which was the theme song for the 1983 movie Papa, Can You Hear Me Sing? (搭錯車). It was remade into a musical in 2018, most recently shown in Taipei last November.

MOTIVES FOR LEAVING

Hou writes that former Government Information Office head James Soong (宋楚瑜) added a few propaganda lines to his song during a speech to military recruits, and his office later pressured the record company to re-record it with the new words. Hou refused.

“It wasn’t that I didn’t like Mr. Soong’s lyrics, or that I didn’t agree with them … I just didn’t want to become a propaganda tool,” Hou writes.

This led to some public backlash against his song in an era where patriotism was top priority.

Hou was later invited to pen a song for the Alliance for China’s Reunification under the Three Principles of the People (三民主義統一中國大同盟), and his friends urged him to accept the offer for the sake of his future. Hou writes that he was struggling financially at that time as he was notoriously difficult to work with.

“I didn’t have the courage to directly refuse them, but I decided to temporarily leave Taiwan,” he writes. “This was not the root cause of why I went to China, but why I began considering leaving.”

In May 1983, Hou headed to Hong Kong to promote his first album, which wasn’t selling well. By early June, he was in Beijing. He was branded a traitor and his songs were banned in Taiwan until martial law was lifted in 1987.

Some question the true motives behind his decision, as censorship and government bureaucracy in China was even worse there. Hou eventually ran afoul of a high-ranking official, who caused him much headache for the next few years; he was even undocumented for a while and was unable to earn any money.

THE PROTESTS

Hou watched the Tiananmen Square demonstrations unfold in 1989. To him, he writes, they were less about democracy, more about “speaking out against one’s dissatisfactions, resisting oppression and breaking free of all shackles.”

Shortly after returning from performing at the Concert For Democracy In China in Hong Kong, Hou was invited by Liu Xiaobo (劉曉波), Gao Xin (高新) and Zhou Duo (周舵) to join their hunger strike on June 2. The situation began worsening the following day, and when the news of troops killing demonstrators around Tiananmen made it to the monument where they sat by June 4, the four decided to evacuate the square.

As a celebrity, Hou helped negotiate with the troops to let the students leave in peace, and writes that he tried hard to convince the students to save their own lives. He watched the last group leave and later sought refuge at the Australian embassy. In August, he told an international documentary crew that he did not personally see anybody get killed within the square. He is often vilified for his comment, but insists that he was just telling the truth.

Gao corroborates this claim in a testament published in 1990 by the Washington Post: “Just as no one needs to exaggerate, or try to alter the fact that there had been huge, bloody confrontations outside the square in other parts of Beijing, it is also a fact that there was no one killed in the square.”

Hou remained in Beijing until May 1990, when he, Gao and Zhou wrote an open letter to the government, calling for the release of Liu and other protestors. The day before the letter was presented, Hou was arrested and given the choice of either going to jail or returning to Taiwan.

The authorities assured him that they would handle all technical issues on the Taiwan side, and several days later escorted him home to pack up. On the morning of June 18, Hou was put on a coast guard boat, which transferred him to a Taiwanese fishing vessel that night. Only then did he find out that the Taiwanese authorities knew nothing about his arrival, and that he was about to face charges of entering illegally.

After going home to see his family, Hou turned himself in. His return received widespread media coverage, much of the opinion of him unfavorable. He eventually left for New Zealand, but in 2011 he surprised the public again by appearing in Beijing and singing Descendants of the Dragon at the Bird’s Nest.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades