Danny Wen (溫士凱) had an eye-opening homecoming experience. First it was the township chief who went to school with his uncle. Then it was the trail builder who knew his mother. There was even a connection with an indigenous Saisiyat elder, who spoke Wen’s Hakka dialect fluently and once stayed at his grandfather’s hotel in Hsinchu County’s Jhudong Township (竹東).

“That hotel closed in the 1970s and I can’t even find old photos of it,” Wen says. “I felt goosebumps all over when he told me that.”

The travel writer and television host didn’t expect his journey through the 270km Raknus Selu trail, which runs through Hakka country from Taoyuan to Taichung, to end up like this. His role as co-host was as a cultural guide and interpreter for British photographer Chris Stowers in AXN channel’s latest documentary, Secrets of the Raknus Selu Trail, but he says he ended up learning just as much.

Photo courtesy of AXN

Stowers is based in Taiwan and has traveled the island extensively, but he knew little about Hakka culture besides dishes commonly found in restaurants.

Stowers is also not used to being in front of the camera, and he’s never narrated a film before. But the production team’s casual, unscripted shooting style quickly put him and Wen at ease. For 20 days, the two bantered and discussed local culture, met up with locals with different expertise along the trail and encountered many unexpected adventures.

The documentary premiered yesterday and will be shown on the channel until the middle of next month, and it can be seen on YouTube starting today. Stowers’ photographs have been made into a book, and they also recorded a four-part podcast that’s available on Spotify and other platforms.

Photo courtesy of AXN

INDUSTRY ROADS

Raknus means camphor in the indigenous Atayal language, while Selu means small road in Hakka. It is the modern name for the roughly 400km network of historic paths dating back to the Qing Dynasty that were once used to transport camphor, tea and other commodities. For the past few years, the Thousand Miles Trail Association (千里步道協會) has been painstakingly restoring and mapping the trails and promoting them to tourists.

“Interestingly, if you ask the people who live along the trail if they know they’re living along the Raknus Selu, they might not know,” Stowers says. “They might say, ‘When I was growing up, it was just a road, we never went further than 20km in any direction.’ But now there’s a growing understanding that they’re part of a bigger picture.”

Photo courtesy of AXN

The same applied to Wen, who’d heard of the trail but never connected it to his past.

“I found out that I knew some of these old paths well,” Wen says. “When I was young, these were industry paths that adults used, and we played on them. After Provincial Highway 3 was built, they fell into disuse. I had no idea I was connected this closely to Raknus Selu.”

Stowers, who is represented by Panos Pictures, is usually busy traveling the world covering news and features, and only because of the COVID-19 pandemic did he have time to embark on this journey. He was still taking photos while being filmed, albeit with a fraction of his usual gear.

Photo courtesy of AXN

“We were seriously walking on the trails, and the objective was to try to do the job with as little equipment as possible. It’s a good mental exercise as a photographer to get back to the basics,” he says.

Wen, who is also a photographer, has traveled extensively during his career.

“From my position, I wanted to know what he saw as a foreigner,” Wen says. “When he took a photo of [trail builder] Grandpa Fan’s hands, he said it reminded him of his father, who also works with his hands. I was moved, because that connection doesn’t just belong to Hakka or indigenous, even if you’re a foreigner, there’s a common emotional language that we can exchange with.”

They developed a quick rapport, forgetting that the camera was there.

“Most of the shooting was done on the first take,” Stowers says. “There was no one telling us what we had to say; some people knew we were coming, and some we just met.”

ON THE TRAIL

Stowers says the trail stands out to him due to its variety.

“Every section is slightly different in topography, vegetation and sights to see,” he says.

The terrain isn’t too difficult, since it runs mostly along the foothills and was built for practical purposes.

“You always have to keep in mind that the whole reason the trail is here is not for fun, it’s for survival and living,” he says.

The weather was fortunately great, and the Tung blossoms started falling shortly after they arrived. Some sections were tougher, as they almost got lost at one point and at another part had to follow a guide hacking through the undergrowth.

“There’s no way I could have done that,” Stowers says. “Without him, I’d still be there now.”

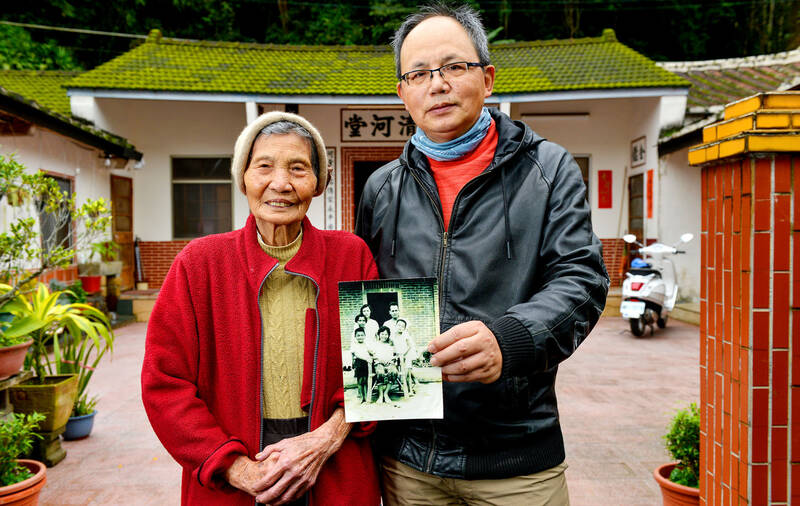

Memorable moments include spending an hour searching for a tea green leafhopper, whose bite changes the leaf into the Oriental Beauty variety, and unexpectedly joining a family feast for their daughter who was moving to Vietnam for a new job. There were three to four generations of the family making signature Hakka glutinous rice balls in the courtyard.

INTRODUCING HISTORY

It’s a daunting task to introduce the tangled history of this land — that even many Taiwanese aren’t clear about — to a foreigner, Wen says, even after more than two decades of studying Hakka culture.

“It’s very hard to just sit there and explain the characteristics of the Hakka,” he says. “But through the people we met and spoke to along the road, we could feel the hospitality and the importance they pay to family history.”

Stowers noticed that most people he met could tell him how many generations they’ve been in Taiwan and where they originated from. Wen is no exception; his family can trace its ancestry back to the Tang Dynasty.

“This is something we’ve been lazy about or lost in the West,” he says. “I guess it’s because my family has never had to move on from where they’ve been. The Hakka are more desperate to keep a hold of something, and even though they’ve settled here for many years and adapted, there’s still some mental link back to the past.”

Having lived abroad for 35 years, Stowers can relate it to his parents’ house in England.

“In the back of my mind, if all goes wrong I can go there, and that’s the one thing I’ll hold on to,” he says. “I tried to think of that, but multiply [my experience] by many generations.”

When they met the indigenous people in Miaoli and Taichung, they realized that the historic tale of encroachment and conflict between the two peoples wasn’t always that clear-cut. There was also intermarriage and cooperation in order to survive in this tough terrain.

Atayal writer and activist Walis Nokan has a photo of an old woman who has indigenous facial tattoos but is dressed in Hakka clothing. That was his grandmother, who received the markings after she married into an indigenous family. They also followed a half-Hakka, half-Saisiyat woman who was digitally documenting her ancestors’ migration routes.

“Not all history is as absolute as you think,” Wen says.

Stowers hopes to come back with his full equipment and take more photos of the locals he met — usually he doesn’t even know the names of his subjects, but due to Wen’s connections and the time spent filming, he developed more of a relationship with them.

“Usually you shoot and move on, but this is different,” he says. “Now I can put a name to a face and know where they live.”

For more information, visit: www.axn-taiwan.com/SecretsoftheRaknusSeluTrail

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)