Oct. 14 to Oct. 20

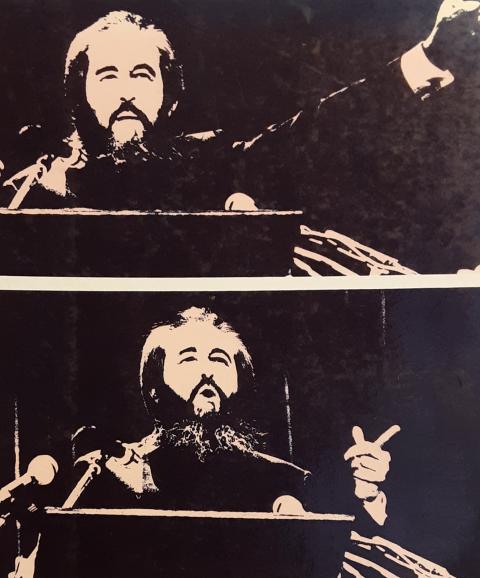

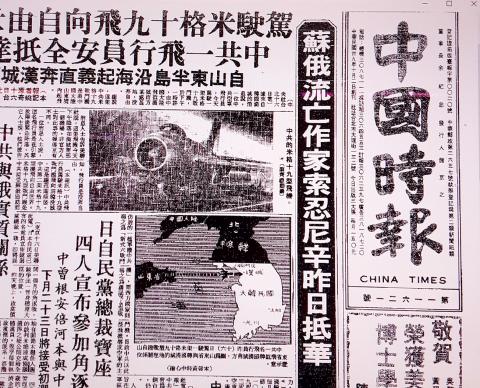

The battle began when 17 media outlets issued a joint statement slamming the China Times on Oct. 18, 1982. A day earlier, the newspaper had announced on its front page the arrival of Nobel Prize-winning Russian writer Aleksander Solzhenitsyn to Taiwan, detailing his visit on page 3.

“Anti-communist writer visits adamantly anti-communist country, his freedom is proof of the freedom and democracy of Taiwan,” ran one of the headlines.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

The paper’s rivals were furious that it jumped the gun despite them collectively promising to not publish anything until Solzhenitsyn made his first public appearance.

“Even though our reporters watched him enter the country ... the majority of newspapers, television and radio stations refrained from publishing anything per the agreement,” the statement read. “But only the China Times violated the agreement, ‘exclusively’ publishing the news of his arrival. This is very unfair because they took advantage of us keeping our word to their own benefit ...”

The China Times issued its own statement the next day, claiming that it had never agreed to the terms, instead criticizing Independence Evening Post (自立晚報) journalist Frank Wu (吳豐山), who coordinated Solzhenitsyn’s visit, for disrespecting press freedom by making such a request. They were especially incensed that as punishment, Wu announced that they would refuse to provide the China Times any press releases or photos and would ban them from attending Solzhenitsyn’s speech the following week.

“Mr. Solzhenitsyn is a man who upholds freedom, especially freedom of speech. We hope that he can fully experience the freedom that is enjoyed in [Taiwan]. We believe that he, as well as our citizens, will not accept any agreement that violates this spirit,” the paper fired back.

SECRETIVE VISIT

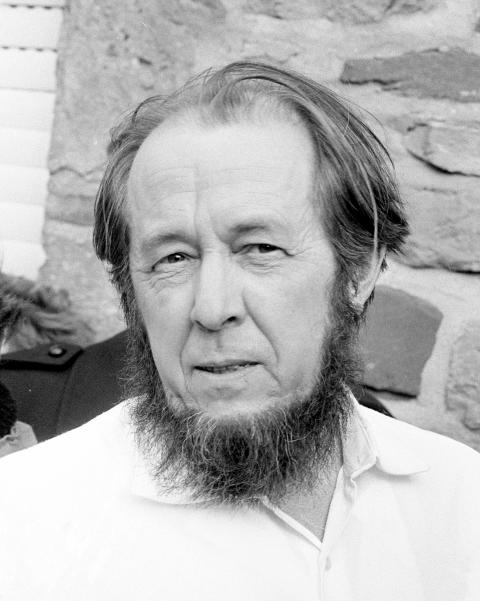

At that time, Solzhenitsyn was living in exile in the US. He was an outspoken critic of the Soviet Union, especially its gulag labor camp system under which he spent 11 years, and his work won him the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1970. After a failed KGB assassination attempt, Solzhenitsyn was expelled from his home country in 1974.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The fact that he agreed to visit Taiwan was big news, as the nation was floundering diplomatically, clinging on to the last vestiges of its claims as “Free China” and a beacon of anti-communism in Asia.

According to Frank Wu, the Wu San-lien Award Foundation first reached out to Solzhenitsyn in June 1981. Three months later, the author agreed to visit on the condition that everything be kept secret until his first public appearance in Taiwan. All correspondence was personally delivered by Wu San-lien’s sons or daughters-in-law as they shuttled between Taiwan and the US. Even so, Wu was not to refer to Solzhenitsyn by name in the letters, but as “Professor Smith.”

After a year of back and forth, Wu was informed on Oct. 9, 1982 that Solzhenitsyn would be arriving in exactly a week. On Oct. 13, Wu gathered members of the local and foreign press, instructing them not to publish anything until Solzhenitsyn gave the green light.

But news photographers descended on the airport to await his arrival on Oct. 16. Wu made them promise not to publish the photos until later, to shoot from a distance and not use flash. The latter request was ignored as the photographers mobbed Solzhenitsyn. He was visibly upset, Wu recalls.

On Oct. 17, Wu had no choice but to inform the writer that the China Times had already reported the news of his arrival. Since English was neither man’s strong suit, it took three hours for Wu to convince the writer that it was the press who disobeyed his instructions. At that point, Solzhenitsyn decided that they might as well announce to the entire nation his arrival, but strongly reiterated his desire to not be bothered.

MEDIA FRENZY

Reporters quickly found out where the writer was staying, and booked rooms in the hotel. One even managed to scale the roof and enter Solzhenitsyn’s room. He refused to answer any questions before she was taken away.

By Oct. 19, both parties realized that it was futile to resist the persistent reporters, and a “motorcade” of about 20 press vehicles followed Solzhenitsyn on his way south, even running red lights to keep up. The first stop was Taichung, where Solzhenitsyn was made an honorary citizen and given a key to the city.

It was a circus wherever he went, as everyone wanted to catch a glimpse of the “big-bearded Russian who appeared in the news everyday,” Wu writes. When Solzhenitsyn asked why he was so popular, his translator told him that the “citizens of Free China’s way of life and attitudes toward personal freedom are in line with his, so they especially welcome him.”

Taiwan was, in fact, under authoritarian rule.

Meanwhile, the newspaper war continued, as the United Daily News accused the China Times of cutting in line in the motorcade, while the China Times pointed fingers at the China Daily News (中華日報).

By the time they reached Kaohsiung, the motorcade had increased to 43 cars. Wu writes that the writer turned down all invitations and gifts by various organizations except a preview of the movie Portrait of a Fanatic (苦戀) that was highly critical of the Cultural Revolution.

On Oct. 23, Solzhenitsyn made his speech, To Free China (給自由中國), where he praised and encouraged Taiwan’s anti-commmunist spirit.

“In China, thanks to a wide strait, a fragment of the former state became the Republic of China on Taiwan, which, for a third of a century, proved to the world what heights of development could have been reached if the whole of China had not fallen under the yoke of Communist hands,” he begins.

He goes on to slam the UN’s exclusion of Taiwan, and especially the US for abandoning the nation for communist China. Finally, he urges Taiwanese to stay vigilant despite a surging economy:

“Do not permit the youth of your country to become soft and placid, to be slaves to material goods, until finally they will prefer slavery and captivity to the struggle of freedom. You are not a serene, carefree island; you are an army, constantly under the menace of war.”

In the end, Solzhenitsyn was able to quietly sneak out of Taiwan. Wu respected his wishes, sending a press release about his departure to the Central News Agency 24 hours after he left.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

We lay transfixed under our blankets as the silhouettes of manta rays temporarily eclipsed the moon above us, and flickers of shadow at our feet revealed smaller fish darting in and out of the shelter of the sunken ship. Unwilling to close our eyes against this magnificent spectacle, we continued to watch, oohing and aahing, until the darkness and the exhaustion of the day’s events finally caught up with us and we fell into a deep slumber. Falling asleep under 1.5 million gallons of seawater in relative comfort was undoubtedly the highlight of the weekend, but the rest of the tour

Youngdoung Tenzin is living history of modern Tibet. The Chinese government on Dec. 22 last year sanctioned him along with 19 other Canadians who were associated with the Canada Tibet Committee and the Uighur Rights Advocacy Project. A former political chair of the Canadian Tibetan Association of Ontario and community outreach manager for the Canada Tibet Committee, he is now a lecturer and researcher in Environmental Chemistry at the University of Toronto. “I was born into a nomadic Tibetan family in Tibet,” he says. “I came to India in 1999, when I was 11. I even met [His Holiness] the 14th the Dalai

Following the rollercoaster ride of 2025, next year is already shaping up to be dramatic. The ongoing constitutional crises and the nine-in-one local elections are already dominating the landscape. The constitutional crises are the ones to lose sleep over. Though much business is still being conducted, crucial items such as next year’s budget, civil servant pensions and the proposed eight-year NT$1.25 trillion (approx US$40 billion) special defense budget are still being contested. There are, however, two glimmers of hope. One is that the legally contested move by five of the eight grand justices on the Constitutional Court’s ad hoc move

Stepping off the busy through-road at Yongan Market Station, lights flashing, horns honking, I turn down a small side street and into the warm embrace of my favorite hole-in-the-wall gem, the Hoi An Banh Mi shop (越南會安麵包), red flags and yellow lanterns waving outside. “Little sister, we were wondering where you’ve been, we haven’t seen you in ages!” the owners call out with a smile. It’s been seven days. The restaurant is run by Huang Jin-chuan (黃錦泉), who is married to a local, and her little sister Eva, who helps out on weekends, having also moved to New Taipei