In 1986, “Anne,” a data entry clerk, watches an IBM PC land on her desk. Within a year, her job is gone. Four decades later, “Natalie,” a social-media manager, looks on as ChatGPT drafts the posts she once wrote. However, her exit might come even faster than Anne’s.

In July, a new report from Microsoft researchers made headlines by listing the 40 occupations most at risk of being replaced by artificial intelligence (AI). It included sales reps, translators, proofreaders and other knowledge jobs, pointing to a looming white-collar employment apocalypse.

However, the report’s authors, and the subsequent news coverage, seem to have overlooked something crucial: The coming disruption would not be gender-neutral. Women comprise most workers in about 60 percent of the occupations listed, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

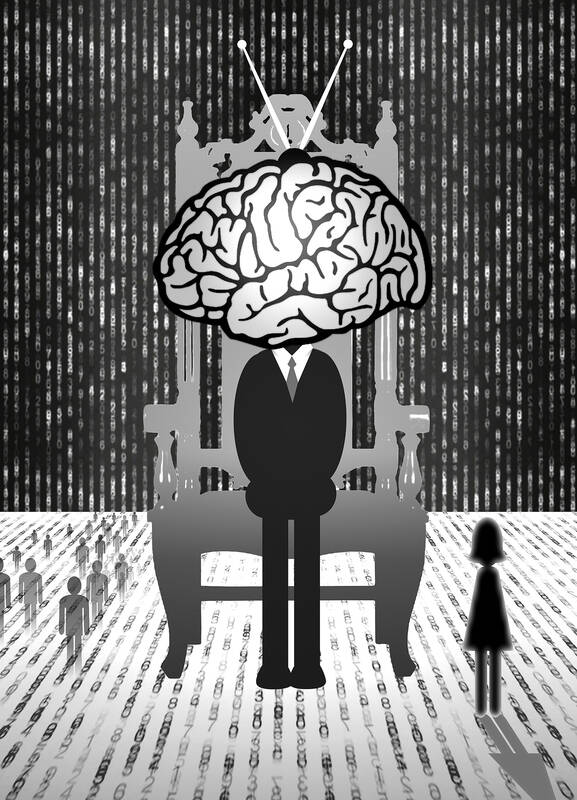

Illustration: Yusha

While AI is out to eat everyone’s lunch, it is women’s lunches the technology looks likely to gobble up first and fastest. Just as the advent of computers in the 1980s displaced legions of secretaries and data-entry clerks — positions held mainly by women — so, too, is this latest wave of automation likely to have a disproportionate impact on female workers. Women’s jobs in high-income countries are about three times more likely to be automated than men’s, a research by the International Labour Organization showed.

The computer revolution serves as a cautionary tale. Many of the women who lost their jobs in the 1980s because of it never recovered, either finding lower-paid work (primarily in the service and care sectors) after protracted periods of unemployment or leaving the workforce altogether. When the BLS tracked the outcomes of workers who were displaced during this period, the findings were stark: Women were more than twice as likely as men to have subsequently dropped out of the labor market.

Given that women are already at an economic disadvantage relative to men — they earn less, own less and retire with less — policymakers need to prepare for AI hitting women’s jobs the hardest and put in place policies to mitigate the impact.

When crafting their response, they would do well to note too that not all secretaries, data-entry clerks and typists fared equally badly in the 1980s: The women who managed to adapt to the technology and acquire relevant new skills had better outcomes.

Set aside, for now, the question of whether the concept of “upskilling” is redundant in an era in which AI is expected to surpass human intelligence, and instead assume that there would be a transitional phase in which workers with AI-related skills do better than those without them. PwC’s 2025 Global AI Jobs Barometer found that workers with AI skills command a 56 percent wage premium, a dramatic increase from the 25 percent wage premium reported the year before.

What this suggests is that if we are to prevent female workers from becoming AI’s most immediate collateral damage, we must ensure that they are fully up to speed on the new technology — or at least as much as their male counterparts.

However, while roughly equal numbers of women and men now use ChatGPT for personal tasks, a clear gender divide has emerged in the workplace. A recent survey of US workers revealed that while 36 percent of men use generative AI daily on the job, only 25 percent of women do. It also reports that 47 percent of men say they are confident using the technology at work, compared with 39 percent of women.

This gap likely reflects the fact that women are more concerned about the increasing use of AI than men — a healthy skepticism people should retain. However, another reason is that companies are investing more in AI upskilling their male employees than they are their female ones. In a global survey of 12,000 professionals conducted this year by Randstad, 41 percent of men said they had been provided with AI access by their employer, compared with 35 percent of women, while 38 percent of men said they had been offered opportunities to build AI skills, compared with 33 percent of women.

Using the technology less — and being given fewer chances to use it — is a toxic combination for female employees, especially as firms increasingly cite “AI fluency” when deciding who to retain and promote.

Failure to address this problem could also expose their employers to legal risk. In the UK, workplace policies that systematically disadvantage women — and offering fewer opportunities for AI upskilling might well fall into this category — could constitute indirect sex discrimination under the Equality Act 2010. This is true even if a firm did not set out to discriminate. Under this law — and similar legislation in other countries — what matters is impact, not intent.

Business leaders should thus be asking themselves basic questions. Who is getting access to AI tools? Who is invited to participate in AI pilots and initiatives? Who is receiving AI training?

Governments around the world seem wholly unprepared for the potential jobs Armageddon that AI could trigger, especially as it affects women. As policymakers develop AI risk-mitigation strategies, it is imperative that gender concerns be firmly on the agenda — and not just for ethical reasons.

At a time when political polarization is increasing and traditional parties are losing ground, winning over female voters is pivotal. As such, ensuring that women do not bear the brunt of AI-induced job displacement, and addressing other AI-related gender disparities as well, is not only the right thing for governments to do. It is also highly pragmatic. After all, there are a lot of Natalies out there.

Noreena Hertz is an honorary professor at the University College London Policy Lab, where she leads research on AI.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

President William Lai (賴清德) attended a dinner held by the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) when representatives from the group visited Taiwan in October. In a speech at the event, Lai highlighted similarities in the geopolitical challenges faced by Israel and Taiwan, saying that the two countries “stand on the front line against authoritarianism.” Lai noted how Taiwan had “immediately condemned” the Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel by Hamas and had provided humanitarian aid. Lai was heavily criticized from some quarters for standing with AIPAC and Israel. On Nov. 4, the Taipei Times published an opinion article (“Speak out on the

Eighty-seven percent of Taiwan’s energy supply this year came from burning fossil fuels, with more than 47 percent of that from gas-fired power generation. The figures attracted international attention since they were in October published in a Reuters report, which highlighted the fragility and structural challenges of Taiwan’s energy sector, accumulated through long-standing policy choices. The nation’s overreliance on natural gas is proving unstable and inadequate. The rising use of natural gas does not project an image of a Taiwan committed to a green energy transition; rather, it seems that Taiwan is attempting to patch up structural gaps in lieu of

News about expanding security cooperation between Israel and Taiwan, including the visits of Deputy Minister of National Defense Po Horng-huei (柏鴻輝) in September and Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) this month, as well as growing ties in areas such as missile defense and cybersecurity, should not be viewed as isolated events. The emphasis on missile defense, including Taiwan’s newly introduced T-Dome project, is simply the most visible sign of a deeper trend that has been taking shape quietly over the past two to three years. Taipei is seeking to expand security and defense cooperation with Israel, something officials

“Can you tell me where the time and motivation will come from to get students to improve their English proficiency in four years of university?” The teacher’s question — not accusatory, just slightly exasperated — was directed at the panelists at the end of a recent conference on English language learning at Taiwanese universities. Perhaps thankfully for the professors on stage, her question was too big for the five minutes remaining. However, it hung over the venue like an ominous cloud on an otherwise sunny-skies day of research into English as a medium of instruction and the government’s Bilingual Nation 2030