Across Botswana the lines of people outside government clinics are lengthening, construction companies dependent on state jobs are firing workers and university students are threatening to boycott lectures after not receiving the allowance increases they were promised.

The economic slowdown is a sharp reversal from just a few years ago when the world’s richest diamond deposits allowed the sparsely populated desert nation of 2.5 million people to invest in free and efficient healthcare, and plow money into funding tertiary education for students at home and abroad. Its robust finances allowed it to provide for its citizens in a way that made it the envy of southern Africa.

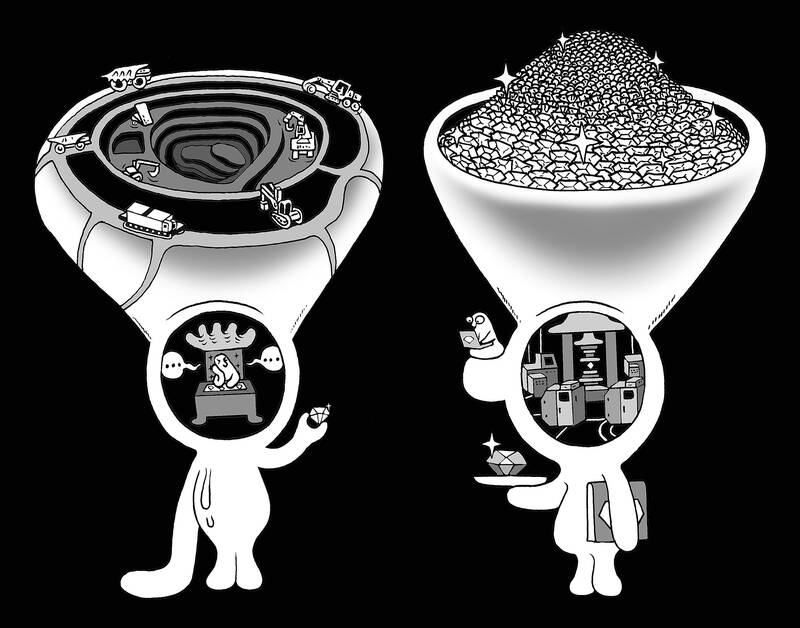

The discovery of gems in 1967 transformed what was a rural backwater with, at the time of independence from the UK a year earlier, only a few kilometers of tarred road into the richest nation per capita on the sub-Saharan African mainland. Six decades later a diamond-market crisis has turned that find into an affliction and a cautionary tale of what can happen to an economy that becomes overly reliant on one commodity.

Illustration: Mountain People

“For decades, we have leaned and relied heavily on diamonds. While they served us well, we know painfully today that this model has reached its limits,” Botswanan President Duma Boko, 55, said in a speech last month. “This is no longer an economic challenge alone; it is a national social existential threat.”

The market for natural diamonds is in crisis, with cut-price lab-grown equivalents hitting demand particularly hard in the US, the biggest market for the gems. They accounted for almost half of engagement ring purchases last year, compared with 5 percent in 2019, according to jewelry insurer BriteCo Inc. The collapse of the luxury retail sector in China and the effects US tariffs have had on trade have also hurt the industry.

While lab gems can be produced in weeks or months, the formation of natural diamonds, made of crystallized carbon formed under extreme pressure and heat deep beneath the Earth’s surface, can take billions of years before volcanic eruptions propel them upward to depths where they can be mined or found on ocean or river beds. They also cost many times as much as their synthetic rivals.

Their increasing popularity is creating the biggest disruption in the market since abundant alluvial diamonds were discovered on Namibia’s beaches early last century, causing prices to plunge, mining historian Duncan Money said.

It is choking off the revenue that accounts for 80 percent of Botswana’s exports and one-third of government income. After repeated write-downs of its value Anglo American PLC is looking to sell De Beers, the world’s biggest diamond company that mines almost all of Botswana’s gems in a venture with the government.

Boko’s administration, which in October last year displaced a political party that had ruled since independence, is scrambling.

In July, the government engaged Malaysia’s PEMANDU Associates to advise on accelerating economic diversification and on Aug. 21, Boko took to Facebook to announce a plan for a little-known Qatari group, Al Mansour Holdings, to invest US$12 billion.

There was scant information about how the capital would be deployed and the same group has in the past few weeks promised more than US$100 billion in investment across six African countries, raising questions about the credibility of the pledge.

The president on Monday last week declared a public health emergency, and implored pension funds and insurers to help fund the response.

The government has frozen recruitment and there are shortages of medication, medical supplies and equipment, Botswana Doctors’ Union president Kefilwe Selema said.

“The situation is very bad,” said Galeemiswe Mosheti, a 42-year-old man with diabetes who arrived at a government clinic in the capital, Gaborone, at 8am and could wait as long as eight hours for his medicine, compared with just an hour a year ago.

“We’re spending long periods in the queue and our jobs suffer,” said the taxi driver who loses income every time he has to wait to be attended to.

For construction companies dependent on government work the situation is no better.

“Most of our members have had to retrench workers,” said Tshotlego Kagiso, chairman of the Tshipidi Badiri Builders Association, the country’s largest building contractors organization, which before the current downturn had more than 800 members, some of whom can no longer afford their membership fees.

“The majority have suspended operations and many have closed altogether due to slower government spending,” he said, adding that thousands of workers have lost their jobs, without being able to be more specific.

The country’s economic statistics tell a story of rapid decline and belie De Beers’ marketing catchphrase: “A diamond is forever.”

The IMF forecast Botswana’s fiscal deficit this year to climb to 11 percent of GDP. That is the largest budget gap since the global financial crisis in 2009, and the biggest in sub-Saharan Africa this year.

Government debt would rocket to 43 percent of GDP this year, about doubling the ratio in just two years, data from the Washington-based lender showed, exceeding a legislative limit.

In June, the Botswanan Ministry of Finance abandoned a forecast of 3.3 percent growth for this year and instead said the economy could contract 0.4 percent. Foreign reserves have slumped 27 percent over the past year and Citigroup Inc in July forecast that Botswana would need to keep devaluing its managed currency, the pula.

A first ever mid-term budget review is planned for as early as next month and Debswana, the country’s joint venture with De Beers, is operating at about 60 percent of capacity.

Botswana is “experiencing a significant decline in revenue inflows resulting in massive liquidity challenges that threaten financial stability and sustainability of government business operations,” Ministry of Finance Permanent Secretary Tshokologo Kganetsano told a parliamentary committee in June.

Already, after years of limited borrowing, the country is turning to debt. It secured US$304 million from the African Development Bank in May and US$200 million from the OPEC fund in July, and had planned a domestic bond roadshow for investors on Tuesday. Its investment grade credit rating, the highest in Africa, is under threat with both Moody’s and S&P Global Ratings this year cutting its outlook to negative.

“The diamond sector is under severe pressure — both prices and volumes,” S&P Global Ratings director and lead analyst Ravi Bhatia said in an interview. “They’re doing a combination of trying to diversify, fiscal consolidation and also austerity.”

While Botswana’s governments have been talking about economic diversification since the country’s first president, Seretse Khama, set up Botswana Development Corp in 1970 to develop copper mining and beef production, little progress has been made.

Tourism, focused on luxury safaris in the country’s Okavango Delta wetlands and a wilderness that boasts the world’s largest elephant population, is the second-biggest contributor after diamonds, accounting for just 12 percent of GDP. Some copper mines are being developed while huge coal deposits, barely exploited, can no longer attract the funding needed for extraction.

That has left more than two-fifths of the population under the age of 24 unemployed, according to the International Labour Organization, with the diamond mines only employing a few thousand people, and reliant on government largesse.

That is a situation Boko described as “a huge risk,” in a January interview with Bloomberg.

“We must now focus on job creation,” Boko said, as he laid out ambitious plans for investment in renewable energy, technology and agriculture.

What he had not bargained for was that there would be no money to pay for it.

While many other countries are reliant on a single commodity for the bulk of their earnings and go through cyclical downturns — for example oil-reliant Nigeria and Angola — for Botswana the outlook is bleaker.

“The difference with the oil cycle is that diamond prices are unlikely to ever come back,” said Charlie Robertson, author of The Time Travelling Economist, a book on how developing economies industrialize. “Its economic model is likely to cease being one of the shining lights on the African continent.”

With assistance from Gordon Bell and Thomas Biesheuvel.

President William Lai (賴清德) attended a dinner held by the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) when representatives from the group visited Taiwan in October. In a speech at the event, Lai highlighted similarities in the geopolitical challenges faced by Israel and Taiwan, saying that the two countries “stand on the front line against authoritarianism.” Lai noted how Taiwan had “immediately condemned” the Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel by Hamas and had provided humanitarian aid. Lai was heavily criticized from some quarters for standing with AIPAC and Israel. On Nov. 4, the Taipei Times published an opinion article (“Speak out on the

Eighty-seven percent of Taiwan’s energy supply this year came from burning fossil fuels, with more than 47 percent of that from gas-fired power generation. The figures attracted international attention since they were in October published in a Reuters report, which highlighted the fragility and structural challenges of Taiwan’s energy sector, accumulated through long-standing policy choices. The nation’s overreliance on natural gas is proving unstable and inadequate. The rising use of natural gas does not project an image of a Taiwan committed to a green energy transition; rather, it seems that Taiwan is attempting to patch up structural gaps in lieu of

News about expanding security cooperation between Israel and Taiwan, including the visits of Deputy Minister of National Defense Po Horng-huei (柏鴻輝) in September and Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) this month, as well as growing ties in areas such as missile defense and cybersecurity, should not be viewed as isolated events. The emphasis on missile defense, including Taiwan’s newly introduced T-Dome project, is simply the most visible sign of a deeper trend that has been taking shape quietly over the past two to three years. Taipei is seeking to expand security and defense cooperation with Israel, something officials

“Can you tell me where the time and motivation will come from to get students to improve their English proficiency in four years of university?” The teacher’s question — not accusatory, just slightly exasperated — was directed at the panelists at the end of a recent conference on English language learning at Taiwanese universities. Perhaps thankfully for the professors on stage, her question was too big for the five minutes remaining. However, it hung over the venue like an ominous cloud on an otherwise sunny-skies day of research into English as a medium of instruction and the government’s Bilingual Nation 2030