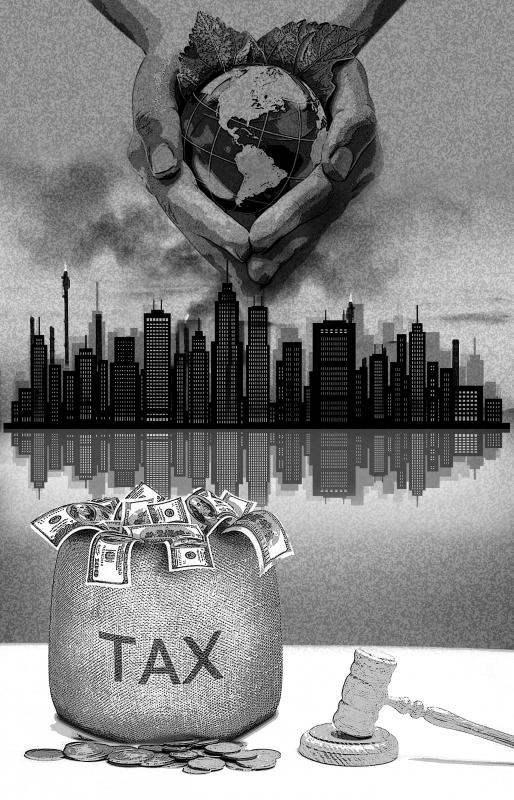

Environmental tariffs might be humanity’s last hope for mitigating climate change, which is on course to become increasingly devastating if we do not curb our greenhouse gas emissions.

The most straightforward way to confront this unprecedented global threat is through a multilateral agreement that locks in a “green transition” in all (or most) countries. The key is to boost renewable-energy production while significantly reducing fossil-fuel consumption, a process that calls for coordinated policies on three fronts: regulation, subsidies for cleaner technologies (including renewables) and carbon taxes.

Unfortunately, this type of global agreement seems out of reach, because the fossil-fuel industry remains politically powerful, and because some of the world’s biggest emitters — including the US, China and India — are not adopting the necessary policies.

Although regulation and subsidies are essential to achieve an effective energy transition, the carbon tax is the bedrock, because that is what will increase the costs of emitting carbon dioxide, methane and other greenhouse gas emissions.

Several countries have already adopted such taxes, including Sweden, which has the world’s highest carbon tax (about US$117 per tonne). Many others, including the US and China, have not followed suit.

This lack of consistency gives rise to “carbon leakage.” High-emissions activities tend to move away from countries with carbon taxes to those without. While a country that unilaterally adopts a higher carbon tax benefits everyone (by reducing its own emissions), it also unwittingly encourages others to do less. As an economist would put it, one should expect that unilateral climate-mitigation policies function as “strategic substitutes” across countries: The higher a country’s carbon tax, the less other countries will do for mitigation.

A high carbon tax creates an opportunity for “carbon arbitrage.” As the steel industry emits 1.68 tonnes of carbon for every tonne of steel produced, Sweden’s carbon tax increases the cost of its steel production by about US$210 per tonne, which in turn makes Chinese steel imports much more attractive for steel users and their customers.

Worse, Chinese authorities have an incentive to maintain this arrangement. Without a Chinese carbon tax, Chinese steel exports would thrive, and that would help Chinese industry, workers and politicians (who can claim credit for generating an economic boom). Even if they recognize the need to combat climate change, Chinese authorities might end up doing less than they might have done without Sweden’s carbon tax.

Hence the need for environmental tariffs, which would reverse this logic by imposing a carbon tax on imports. Sweden would apply a border tax adjustment equivalent to the difference between its carbon tax and the carbon tax of the exporting country, multiplied by the tonnage of the carbon emissions generated in the production of the imported products.

An environmental tariff’s most obvious benefit is that it reduces carbon leakage. By nullifying the artificial cost advantage of imports from low-carbon-tax countries, it encourages steel consumption to shift toward cleaner domestic sources or less-polluting exporters.

An environmental tariff’s indirect effects might be even more important. A tariff makes climate-change mitigation policies “strategic complements” rather than strategic substitutes; this means that Swedish carbon taxes would encourage, rather than discourage, other countries to adopt similar policies of their own.

The logic is simple: Without environmental tariffs, Sweden’s carbon tax gives Chinese steel producers an arbitrage opportunity. Once more countries begin to apply border adjustments on imports, the Chinese authorities would want to help China’s steel exporters clean up their operations. Regardless of whether they do this through carbon taxes, regulations or subsidies for clean energy, Chinese carbon emissions would decline. Once Chinese producers start meaningfully reducing their emissions, China’s authorities would have an incentive to introduce environmental tariffs of their own.

For the most part, what is standing in the way of aggressive environmental tariffs are excuses and misleading arguments. The fossil-fuel industry and major polluters, including China, are dead set against environmental tariffs and have been campaigning aggressively to block them. This position is wholly selfish and should be disregarded.

A second argument is that environmental tariffs are protectionist measures, and that we should not “risk giving protectionists another opening,” as The Economist puts it. This claim does not hold water. Because carbon tariffs level the playing field, they do not function like traditional protectionist measures.

Moreover, the classic theory of trade does not imply that arbitraging domestic policies produces welfare gains — especially considering that such policies are essential for combating climate change.

A third objection is that environmental tariffs might not be legal under WTO rules. A straightforward reading of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) suggests that they are legal. Article III allows for environmental taxes, stating that imported products “shall not be subject, directly or indirectly, to internal taxes or other internal charges of any kind in excess of those applied, directly or indirectly, to like domestic products.” It follows that if a country has a domestic carbon tax on “like domestic products,” it is permitted to apply the same tax to imports through border adjustments.

This rule has long provided the basis for border adjustments on value-added taxes, and it was also the reasoning behind a GATT panel’s 1987 ruling (in “United States – Taxes on Petroleum and Certain Important Substances”) that border tax adjustments could be applied to chemicals.

Furthermore, Article XX of the GATT provides additional exemptions for trade restrictions “necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health,” and there is a strong scientific case that carbon taxes meet that criteria.

Some commentators worry that in a “liberal international order,” important global policy decisions should be pursued primarily through multilateral cooperation. That might well be true, but multilateral agreements are not going to work fast enough to keep the world anywhere close to the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C warming pathway. We cannot allow faith in multilateralism to become an alibi for inaction. Environmental tariffs could create a positive cascade of climate-mitigation policies around the world. There should be no delay in implementing them.

Daron Acemoglu is a professor of economics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and coauthor of Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty and The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

A foreign colleague of mine asked me recently, “What is a safe distance from potential People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Rocket Force’s (PLARF) Taiwan targets?” This article will answer this question and help people living in Taiwan have a deeper understanding of the threat. Why is it important to understand PLA/PLARF targeting strategy? According to RAND analysis, the PLA’s “systems destruction warfare” focuses on crippling an adversary’s operational system by targeting its networks, especially leadership, command and control (C2) nodes, sensors, and information hubs. Admiral Samuel Paparo, commander of US Indo-Pacific Command, noted in his 15 May 2025 Sedona Forum keynote speech that, as

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) last week announced that the KMT was launching “Operation Patriot” in response to an unprecedented massive campaign to recall 31 KMT legislators. However, his action has also raised questions and doubts: Are these so-called “patriots” pledging allegiance to the country or to the party? While all KMT-proposed campaigns to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmakers have failed, and a growing number of local KMT chapter personnel have been indicted for allegedly forging petition signatures, media reports said that at least 26 recall motions against KMT legislators have passed the second signature threshold

The Central Election Commission (CEC) on Friday announced that recall motions targeting 24 Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers and Hsinchu Mayor Ann Kao (高虹安) have been approved, and that a recall vote would take place on July 26. Of the recall motions against 35 KMT legislators, 31 were reviewed by the CEC after they exceeded the second-phase signature thresholds. Twenty-four were approved, five were asked to submit additional signatures to make up for invalid ones and two are still being reviewed. The mass recall vote targeting so many lawmakers at once is unprecedented in Taiwan’s political history. If the KMT loses more

In a world increasingly defined by unpredictability, two actors stand out as islands of stability: Europe and Taiwan. One, a sprawling union of democracies, but under immense pressure, grappling with a geopolitical reality it was not originally designed for. The other, a vibrant, resilient democracy thriving as a technological global leader, but living under a growing existential threat. In response to rising uncertainties, they are both seeking resilience and learning to better position themselves. It is now time they recognize each other not just as partners of convenience, but as strategic and indispensable lifelines. The US, long seen as the anchor