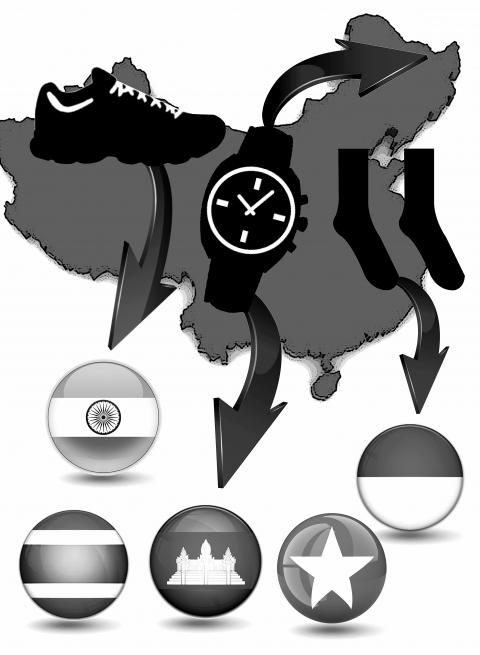

From socks and sneakers to washing machines and watches, Asian countries are hoping the US-China trade dispute will permanently boost manufacturing as brands dodge the row by choosing cheaper locations to make their goods.

Business has fanned out from China, often referred to as the “Factory of the World,” into Vietnam, Cambodia, India and Indonesia for years.

However, the shift has accelerated as the world’s two biggest economies slap tit-for-tat tariffs on each other. In the latest round of the bruising spat, US President Donald Trump last month raised tariffs to 25 percent on US$200 billion of Chinese goods, prompting Beijing to retaliate with higher duties on US$60 billion worth of American products.

Illustration: Constance Chou

That “really became a kicker to force people to move,” said Trent Davies, manager of international business at advisory and tax firm Dezan Shira & Associates in Vietnam.

A surge in relocations from China or plans to scale up production has strengthened the manufacturing hubs of Southeast Asia and beyond.

Casio said it was moving some of its watch production to Thailand and Japan to avoid the US penalties, while Japanese printer maker Ricoh said it was also shifting some of its work to Thailand. US shoe giant Steve Madden plans to boost production in Cambodia, and Brooks Running Co, Haier washing machines and sock maker Jasan — which sells to Adidas, Puma, New Balance and Fila — are all eyeing Vietnam.

The country is a logical move for manufacturers, wooed by low-cost labor, attractive tax incentives and close proximity to China’s unparalleled supply chains.

“It’s not just a result of the trade war, a lot of it is opportunity in Vietnam,” Davies said.

Some Vietnamese suppliers say the trade dispute has fast-tracked the trend as companies scramble to dodge fresh tariffs that could affect about 4,000 categories of exports to the US.

On a busy stretch of road in Hanoi, the bustling Garco 10 factory is churning out men’s shirts for American brands like Hollister, Bonobos and Express.

The company says exports to the US were up 7 percent last year, with an expected 10 percent jump this year.

“Thanks to the trade war ... several sectors of the Vietnam economy have gained, especially our garment sector,” Garco 10 director Than Duc Viet told reporters.

“We want to open more factories, we want to expand our capacity,” he said at one of his facilities where an army of workers made shirts destined for American shopping malls and department stores.

US imports from China during the first three months of this year reached nearly US$16 billion, up 40 percent from the same period last year, according to US trade data.

And that number could rise.

More than 40 percent of US companies in China are now considering moving or have already done so, mainly to Southeast Asia or Mexico, according to a poll this month by the American Chamber of Commerce in China.

However, the shift is not expected to be seamless. While Southeast Asia offers low-cost labor — monthly factory salaries are about US$290 in Vietnam and US$180 in Cambodia and Indonesia, compared with about US$540 in China — workers are less experienced.

“Labour costs are three times higher in China, but the efficiency is also three times higher,” said Frank Weiand, cochair of the manufacturing committee at the American Chamber of Commerce in Vietnam.

There is also a smaller labor pool to draw on.

Vietnam employs about 10 million people in the manufacturing sector compared with 166 million in China, according to data from the International Labour Organization. Indonesia employs 17.5 million and Cambodia 1.4 million.

Experts warn that companies might also face supply chain woes, infrastructure challenges and land shortages in less-developed markets without the capacity to absorb overspill from China.

This could be a problem for Indonesia, whose clunky bureaucracy has left it trailing some of its neighbors.

However, now the country is hoping to soak up foreign investment from the trade dispute.

“We’re trying to make it easier for investors by speeding up the process for getting business permits,” said Yuliot, a senior official at the Indonesian Investment Board, who goes by one name.

The country is also beefing up infrastructure and skills training while offering corporate tax breaks, he said.

With no end to the trade dispute in sight, analysts say the manufacturing shift out of China is likely to continue and could redefine long-entrenched global trade patterns.

“Certainly it will end China’s dominance as the ‘Factory for the US,’” Gary Hufbauer, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, told reporters.

US companies and consumers might also get the short end of the stick: higher tariffs on goods out of China means the average American will likely have to pay more for a pair of Nike sneakers or Levi’s jeans.

And if Trump was hoping to drive US manufacturers back home by imposing those tariffs as part of his “Make America Great Again” clarion call, he is not likely to get his wish.

US industries — and wages — are not set up for low-cost manufacturing on the scale of China. Instead, countries like Vietnam are likely to continue scooping up those jobs.

Le Thi Huong, who sews hems at Hanoi’s Garco 10 factory, said: “I hope there will be more orders ... so we have more jobs and more income.”

There is much evidence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is sending soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and is learning lessons for a future war against Taiwan. Until now, the CCP has claimed that they have not sent PLA personnel to support Russian aggression. On 18 April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelinskiy announced that the CCP is supplying war supplies such as gunpowder, artillery, and weapons subcomponents to Russia. When Zelinskiy announced on 9 April that the Ukrainian Army had captured two Chinese nationals fighting with Russians on the front line with details

Within Taiwan’s education system exists a long-standing and deep-rooted culture of falsification. In the past month, a large number of “ghost signatures” — signatures using the names of deceased people — appeared on recall petitions submitted by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) against Democratic Progressive Party legislators Rosalia Wu (吳思瑤) and Wu Pei-yi (吳沛憶). An investigation revealed a high degree of overlap between the deceased signatories and the KMT’s membership roster. It also showed that documents had been forged. However, that culture of cheating and fabrication did not just appear out of thin air — it is linked to the

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), joined by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), held a protest on Saturday on Ketagalan Boulevard in Taipei. They were essentially standing for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which is anxious about the mass recall campaign against KMT legislators. President William Lai (賴清德) said that if the opposition parties truly wanted to fight dictatorship, they should do so in Tiananmen Square — and at the very least, refrain from groveling to Chinese officials during their visits to China, alluding to meetings between KMT members and Chinese authorities. Now that China has been defined as a foreign hostile force,

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to