April 28 to May 4

During the Japanese colonial era, a city’s “first” high school typically served Japanese students, while Taiwanese attended the “second” high school. Only in Taichung was this reversed.

That’s because when Taichung First High School opened its doors on May 1, 1915 to serve Taiwanese students who were previously barred from secondary education, it was the only high school in town. Former principal Hideo Azukisawa threatened to quit when the government in 1922 attempted to transfer the “first” designation to a new local high school for Japanese students, leading to this unusual situation.

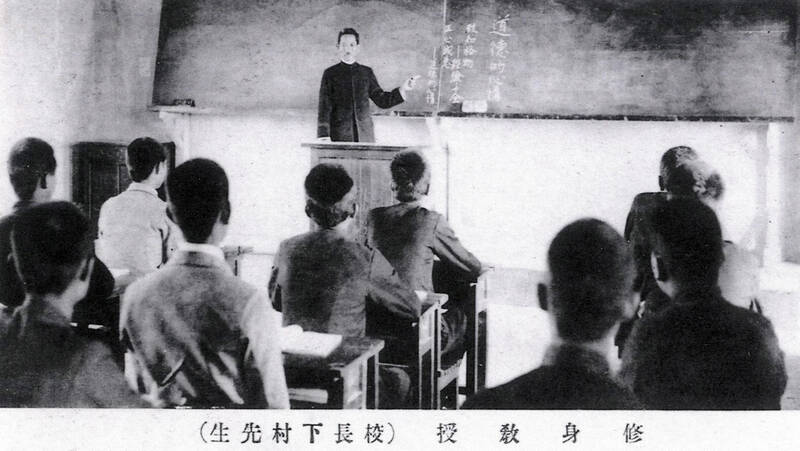

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Culture Memory Bank

Prior to the Taichung First High School’s establishment, there were only two secondary schools in Taiwan, both only accepting Japanese students. After finishing elementary school, Taiwanese could only attend certain vocational institutions or further their studies in Japan or China. In 1912, prominent locals in central Taiwan began petitioning the governor general to open a high school for Taiwanese students, finally getting their wish in 1914.

Although funded and built by Taiwanese, the four-year institution was run and almost exclusively staffed by Japanese. At first the curriculum differed from Japanese schools, and the system was designed so that its graduates could not continue their studies in Japan (there were no universities in Taiwan at the time).

With enrollment capped at 600 students, educational opportunities remained limited for Taiwanese and the school still mainly served well-off families. Only with the Taiwan Education Act of 1922 would this situation change.

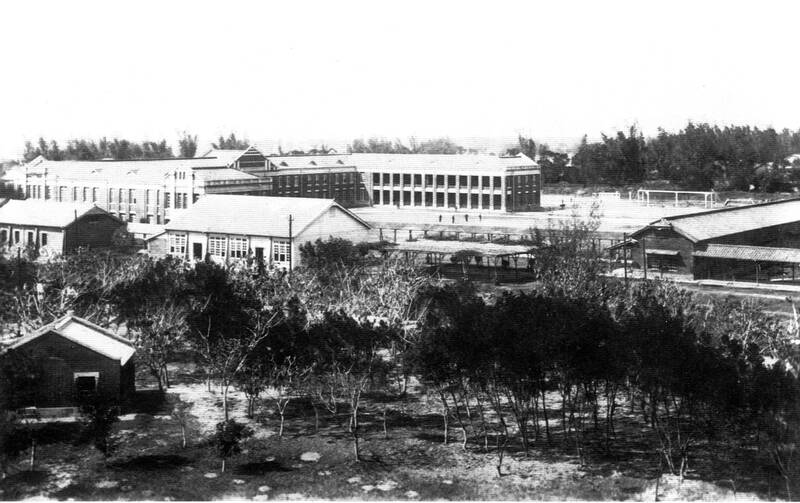

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

BARRED FROM SECONDARY SCHOOL

After taking over Taiwan in 1895, the colonial government’s primary educational goal for Taiwanese was to make them proficient in Japanese, opening up language institutions and later public elementary schools.

“The goal was not to raise the educational level of Taiwanese, so secondary institutions were not part of colonial policy unless necessary,” writes Chu Pei-chi (朱珮琪) in The Cradle for Taiwanese Elites: Taichung First High School (台籍菁英的搖籃: 台中一中).

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Culture Memory Bank

After graduating from elementary school, Japanese children could continue their studies through secondary programs in the same institution, while Taiwanese who had means moved on to vocational training or headed to Japan or China.

In response to the increasing number of Japanese families settling in Taiwan, the Governor General’s High School was established in Taipei in 1907, offering five and six year programs with additional one and two year options identical to the Japanese school system. This school became today’s Taipei Municipality Chien Kuo High School.

The issue of education for Taiwanese became a talking point at a 1912 gathering at the prominent Wufeng Lin (霧峰林家) family’s mansion. The Lin matriarch’s 80th birthday was coming up, and someone suggested that instead of throwing a lavish celebration, they should save the money as a scholarship fund for the students studying abroad. After much discussion, they decided to be even more proactive and start a private secondary school.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

A SCHOOL FOR TAIWANESE

In September 1913, a group led by Koo Hsien-jung (辜顯榮) brought the idea to governor general Samata Sakuma. Their petition stated that they were pouring a lot of money into supporting Taiwanese students studying in Japan, and if the government set up a secondary school for them in Taiwan, they could use these funds to instead build the school and cover other costs.

The Japanese Diet opposed the idea. For them, colonial education should focus on vocational training to develop a quality workforce; too much general, high-level education would expose Taiwanese to new ideas and make them hard to rule.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Nevertheless, Sakuma approved their request, with the condition that the petitioners would fund construction and supplies, and that the government would own the school and control the curriculum.

Chu cites several reasons why the Japanese authorities agreed to the school. They wanted the support of these wealthy Taiwanese elites, especially during a time when the government was draining its resources trying to subdue the remaining hostile indigenous communities. They also hoped to train a group of loyal, educated Taiwanese to help them develop the colony. And as many Taiwanese identified with China and resented Japanese rule, they were worried that the students sent to China would develop revolutionary ideals and cause trouble.

A committee was set up to bring this school to fruition, comprised of Koo, Lin Hsien-tang (林獻堂), Lin Lie-tang (林烈堂), Tsai Lien-fang (蔡蓮舫) and Lin Hsiung-cheng (林熊徵), who are today considered the school’s five founding fathers. The final donor list totaled 204 people, but the five founding fathers alone contributed 36 percent of the funds.

INFERIOR CURRICULUM

Classes started on May 1, 1915, but construction had yet to begin due to bidding issues. For the first year, they used the old campus of Taichung Elementary School, which was cramped and in disrepair.

Nevertheless, the opening ceremony was a grand affair, with the chief of home affairs Kakichi Uchida (the second highest colonial officer) as the guest of honor. Afterwards, a banquet was thrown with about 200 officials and prominent civilians in attendance.

The governor general appointed all the administrators and staff, including first principal Shinichu Tagawa, who had plenty of secondary school experience in Japan. Although Tawaga admitted to not knowing much about Taiwanese education and customs when he arrived, he put great effort into improving the school, and is remembered as a kind and gentle educator who did not discriminate against Taiwanese.

There were only two Taiwanese staff, both part-time instructors who taught Chinese and calligraphy. Lin Ching (林慶) was later promoted to full time and taught there for 22 years, and for most of his tenure he was the school’s only regular Taiwanese teacher.

Although this school shared the “high school” designation with its Taipei counterpart, the curriculum did not follow Japanese standards, Chu writes, something the founding committee didn’t learn about until the school was about to open. For starters, it was a four year program, just short of the five years required to continue up the educational ladder in Japan. There were much fewer English and science classes, making it hard for students to compete. All students were also required to board at the school.

This situation continued until 1922, when the government decided to grant Taiwanese the same educational privileges as part of its plan to assimilate them as patriotic Japanese citizens. Next week’s feature will look at how this act affected Taichung First High School, as well as the notable student strike and subsequent mass expulsion of 1927.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,