Nov. 3 to Nov. 9

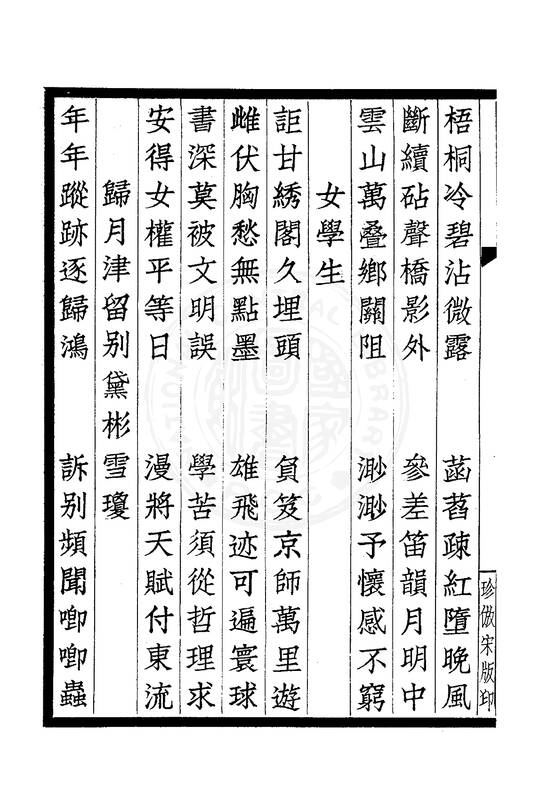

In 1925, 18-year-old Huang Chin-chuan (黃金川) penned the following words: “When will the day of women’s equal rights arrive, so that my talents won’t drift away in the eastern stream?”

These were the closing lines to her poem “Female Student” (女學生), which expressed her unwillingness to be confined to traditional female roles and her desire to study and explore the world.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Born to a wealthy family on Nov. 5, 1907, Huang was able to study in Japan — a rare privilege for women in her time — and even made a name for herself in the male-dominated classical poetry scene after returning to Taiwan.

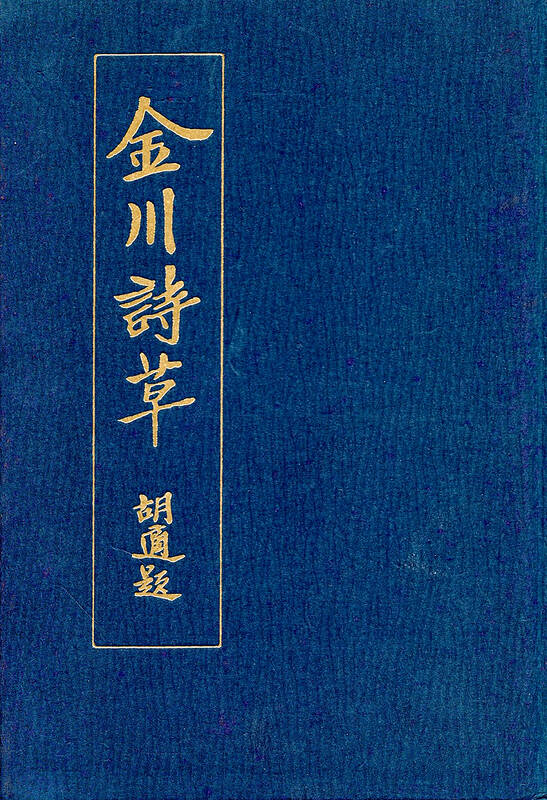

The poem was one of 240 works included in the 1930 Poetry of Chin-chuan (金川詩草), making Huang the first Taiwanese woman to have her own poetry collection.

Yet, as she once feared, she soon faded into domestic life as the daughter-in-law of Kaohsiung’s richest man, bearing eight children in a marriage that was neither of her choosing nor particularly happy.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Huang continued to write intermittently, though her verses became more melancholy. In several poems, she wondered if life might have been easier if she were not talented. After her death in 1990, her children added an additional 119 poems to her collection, revealing the contrast between the two phases of her life.

STRICT UPBRINGING

Historian Lin Tsui-feng (林翠鳳) details Huang’s early life in “Huang Chin-chuan’s poetic development and analysis of ‘Poetry of Chin-chuan’.”

Photo courtesy of The World of Dr Hu Shih

Huang’s grandfather made his fortune in the sugar industry, establishing the family as one of the most prominent in Tainan’s Yanshuei District (鹽水). Her father died when she was just a year old, but her mother Tsai Yin (蔡寅) stepped up, managing and expanding the family’s estates and businesses while raising her three children.

Once considered the most beautiful woman in Chiayi County’s Budai Township (布袋), Tsai received a traditional Chinese education, developing a love for literature and poetry. Despite having bound feet that made it difficult to walk, she was very hands-on and strict about her children’s education. With opportunities limited for Taiwanese in Taiwan (most resources went to Japanese students), she moved the family to Japan.

Huang enrolled in Seika Girls High School, where her mother closely supervised her studies. Huang’s daughter later recalled her mother doing the same, even sitting in on classes — the school had to place a chair at the back of the room for her.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Huang started writing poetry during this period. As the foreword to her collection states, she returned to Taiwan in 1924 with a “suitcase full of manuscripts.”

EMERGING TALENT

Huang joined Tsai Che-jen’s (蔡哲人) Moon Harbor Poetry Society (月津詩社), named for the curved shape of Yanshuei’s port. Her second-eldest brother Huang Chao-pi (黃朝碧) served as the group’s vice-president. The society aimed to promote classical poetry to preserve Han Taiwanese culture under Japanese rule. Such groups flourished during the 1920s, their popularization giving women more opportunities to participate. In 1930, the first all-women poetry association appeared.

Huang and her mother later moved to Tainan City, where she became the disciple of Shih Mei-chiao (施梅樵). Shih wrote in the foreword to Huang’s collection, “Her prose is clear and delightful. Within just a few months, her poetic inspiration flowed like a spring, and her name quickly spread through literary circles.”

Over the next few years, Huang published frequently and participated in poetry gatherings as far as Taoyuan’s Jhongli District (中壢), even hosting an even at her home once. She sought guidance from masters such as Wang Chu-hsiu (王竹修) and Chao Yun-shih (趙雲石), composing many verses dedicated to these groups.

She also toured Taiwan’s sights, “writing about every place she visited, bringing mountains, rivers and trees vividly to life,” Wang writes.

Locals called her the “imperial scholar without a comb” — a traditional term for gifted women barred from government examinations due to gender.

As the youngest and only daughter of an upper-class family with a gentle, soft-spoken nature, Huang’s social circle and activities were limited, spending much time at home alone — but she established lasting friendships with other female poets, and they dedicated poems to each other.

FIRST COLLECTION

At the age of 23, Huang married Chen Chi-ching (陳啟清), the eighth son of magnate Chen Chung-ho (陳中和). Chen Chi-ching was handsome and capable, but Huang seemed apprehensive — especially as he already had a son with his first wife who had died, writes Chen Chia-ying (陳嘉英) in “Female voices searching for a space — female poets Chang-Lee Te-he, Shih Chung-ying and Huang Chin-chuan as case studies” (尋找空間的女聲以台灣女詩人張李德和、石中英、黃金川為探究對象).

Nevertheless, Huang’s family considered it a suitable match, and her eldest brother, Huang Chao-chin (黃朝琴), offered a copy of the 1,000-volume Complete Library of the Four Treasuries (四庫全書) as part of the dowry. Chen later took concubines, as customary in those days, causing much family tension and adding to Huang’s sorrow.

A year later, Huang Chao-chin could not bear to see his sister’s work fade away. After studying in the US, he went to China and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), working as an agent for the Overseas Chinese Affairs Commission. He had the collection published through Shanghai’s Zhong Hua Book Company, with prominent scholars and politicians contributing calligraphy. They didn’t just admire her prose, it was a testament to colonized people striving to preserve Han culture. Noted academic Hu Shih (胡適) provided the cover text and wrote an inscription inside: “Lingering voice of the ancestral land” (宗國遺音).

This first collection contained a broad range of topics. Many poems were dedicated to her family, especially her mother, while others reflected her daily life, observations and emotions. She wrote about historical female figures such as Hua Mulan and Wang Zhaojun (王昭君), as well as scenery and changes in the seasons.

Several pieces describe the laborious lives of female silk worm farmers and the devastation caused by the 1927 Tainan earthquake.

Although she noted the hardships faced by these farmers, she admired their ability to provide for themselves, adding that they need not envy the lives of those who wore the silk they produced.

RESIGNING TO FATE

Although Huang worried about her future and often felt stifled and lonely, her early poems were upbeat, curious about the world and often focused on the beauty of spring and summer, Chen writes. The second collection was much more somber and narrow in scope, lamenting her unhappy home life and the restrictions placed upon her as a woman.

In one verse, she mourns that her talents were wasted and that she had become a mere puppet, questioning what she had sacrificed for. By all accounts, she remained a devoted wife and mother, even being named Exemplary Mother of Kaohsiung in 1963 — but it was not the life she had chosen.

“Alas, born in this useless woman’s body, I bear the age-old injustices and cannot fulfill my ambitions,” she laments in one poem.

In another: “If I had known I couldn’t use my talents, I would not have spent all my gold to buy books.”

And finally, “Reciting from the jade-bound book, I am on the verge of tears. What more could one seek when talent goes unrecognized? Ordinary people have since ancient times been considered more fortunate, if one learns to be ordinary, then one need not worry anymore.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global

Taiwan’s democracy is at risk. Be very alarmed. This is not a drill. The current constitutional crisis progressed slowly, then suddenly. Political tensions, partisan hostility and emotions are all running high right when cool heads and calm negotiation are most needed. Oxford defines brinkmanship as: “The art or practice of pursuing a dangerous policy to the limits of safety before stopping, especially in politics.” It says the term comes from a quote from a 1956 Cold War interview with then-American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, when he said: ‘The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is

Like much in the world today, theater has experienced major disruptions over the six years since COVID-19. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and social media have created a new normal of geopolitical and information uncertainty, and the performing arts are not immune to these effects. “Ten years ago people wanted to come to the theater to engage with important issues, but now the Internet allows them to engage with those issues powerfully and immediately,” said Faith Tan, programming director of the Esplanade in Singapore, speaking last week in Japan. “One reaction to unpredictability has been a renewed emphasis on