For much of the world, it is a niche product. In North Korea, where winter temperatures are frigid and which cannot produce enough cotton or wool for clothing, the synthetic fiber developed after nylon was glorified as a revolutionary invention.

Known outside North Korea as vinylon, it was christened “vinalon” by the nation’s founder, former North Korean leader Kim Il-sung. He ordered that it be developed to put clothes on people’s backs.

It is a story which reveals much about the history of North Korea.

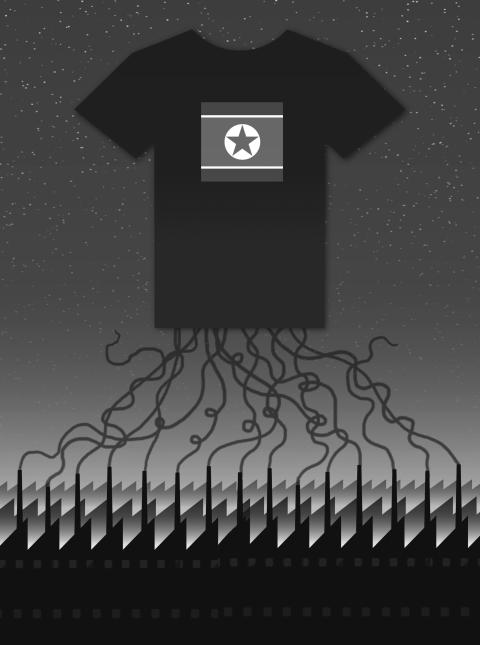

Illustration: Yusha

The state says the fiber symbolizes its self-reliance, but diplomatic records show that the project was less successful than Kim had hoped — Pyongyang was more dependent on others than it claimed.

The North Korean government does not provide foreign media with a point of contact in Pyongyang and the country’s delegation to the UN did not respond to a request for comment.

WONDER FABRIC

The global vinylon fiber industry was worth US$443 million in 2016 and is projected to reach US$539 million by 2022, according to Orbis Research.

Swedish outdoor clothing company Fjallraven uses a form of vinylon, Vinylon F from Japan, in products including the Kanken backpack.

Fjallraven does not source material from North Korea, a company spokesman said.

Companies in Japan and China make vinylon based on petroleum, but North Korea has no oil reserves. Instead it makes vinalon from two commodities it has in abundance: coal and limestone.

The process starts with workers mining anthracite and breaking limestones.

Vinalon dates back to 1939, two years after DuPont of the US introduced nylon — and with it affordable stockings, American glamor and movie stars.

At the time, North Korea was part of Japan and nylon was undercutting Japanese silk and cotton exports. A Korean scientist was on the team at Kyoto University that developed an alternative fiber. His name was Ri Sung-gi.

Ri’s invention starts out as hard, white crystals that look like sea salt. However, once drawn out and spun into a thread, it acquires a texture like cotton. It is stiff and hard to dye, but strong.

It was promising, but two wars interrupted Ri’s efforts to develop his fabric.

In 1948, after World War II, North Korea became a communist state.

The North Koreans invaded the South and in the ensuing three years, the US bombed Pyongyang.

About 2.5 million soldiers and civilians died on both sides, according to the South Korean Ministry of Defense.

In 1953, the Korean War paused with a truce.

Ri wanted to help rebuild. He offered to develop his fabric in South Korea. The South, which was allied with the US, was not interested.

At this time, all Soviet states were driving for technological prowess. The North was courting foreign scientists and it did what it could to keep hold of them.

Ri defected. North Korea likened him to Marie Curie, the French chemist who developed the theory of radioactivity.

“To bore a hole into the heart of US imperialism, I have been peering through microscopes and shaking my test tubes with determination,” Ri Sung-gi wrote in his memoirs.

JUCHE

The Soviet Union was forging ahead. On April 12, 1961, Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin beat the US to be the first man in space. Joseph Stalin sponsored Kim as founder of North Korea.

Under Japanese rule, the North had received more investment in heavy industry than the South and it had ample energy.

However, North Korea needed overcoats for its people, Kim told then-Soviet ambassador to North Korea A.M. Puzanov.

“If we do not solve the clothing problem, it will be hard to compete with the South,” he said, according to Puzanov’s journal.

The Soviet Union could not help supply cotton.

Ri had proven in lab tests that vinalon could be made. Kim saw the fiber as a political tool.

He created an ideology of self-reliance known as juche. The word translates literally as “subject,” but stands for the notion that man is the master of his own destiny.

Kim said vinalon was the “juche fiber.”

“The vinalon industry is the shining fruition that the juche idea of our Party was reflected in the field of chemical industry,” Kim said in 1967.

On May 6 1961, he held an opening ceremony for the February 8 Vinalon Plant in Hamhung, in the country’s South Hamgyong Province.

Kim was telling his allies that North Korea could produce 10,000 tonnes of vinalon a year and would soon be producing more than 300 million meters of textiles a year, documents in the Wilson Center archive show.

The factory, built by a division of the Korean People’s Army working on three shifts of 3,000 people, went up so quickly that the triumphal phrase “vinalon speed” emerged in state propaganda.

Looking at the first vinalon strands, Ri said they were “white as snow and lighter than a dandelion puff.”

Kim Sung-hee, a North Korean who defected to the South, said she attended the ribbon-cutting ceremony.

“Inside the factory I saw pink and red jackets. Even after 15 years, the vinalon jackets did not get frayed, although the colors could change a bit,” she said.

Defectors born before the 1980s have said they used to wear jackets, school uniforms and socks made of vinalon.

The fiber was part of an industrial drive like the one Mao Zedong (毛澤東) launched in China. North Korea’s effort was known as Chollima. Embodied by a flying horse, it galvanized workers into skipping breaks to boost productivity, helped by slogans such as “drink no soup.”

In 1961, Kim Il-sung met his comrade, then-Chinese politburo member Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平), and told him that North Korea had “already succeeded” in producing vinalon to ease the country’s clothing problem.

Deng said the process demanded electricity, but Kim was not worried.

“We will not need to use electricity in future. We can use oxygen,” Kim said.

PEOPLE’S ECONOMY

In the early 1960s, as an anti-communist coup in South Korea and the Cuban missile crisis sent North Korea down a path of military buildup, the economy was growing fast.

Cambridge University economist Joan Robinson visited in 1964 and wrote that “all the economic miracles of the postwar world are put into the shade” by what she saw, including vinalon.

She recorded the formula for making it.

The North grew faster than the South — a trend which continued into the 1970s, according to UN and CIA economic data.

In 1972, the CIA recorded figures from 1956 to 1971 that showed the North had produced 7 million more meters of textiles than the South. In the early years, the North’s output of fish products, coal, iron ore, steel, cement, chemical fertilizers and tractors also exceeded that of the South.

The CIA figures show that until the mid-1960s, the North consistently exported more than the South in dollar terms.

KING OF FIBERS

North Koreans called vinalon “the King of Fibers” and featured it in cartoons to teach children how independent and successful the country was.

A TV show from 1976 shows Vinalon Man win a race against Mr Nylon.

However, in reality, the fabric’s limits were emerging. It was not good at keeping people warm and power was becoming a problem in its production.

By now, oil was cheap in the West and the outside world was using it in abundance for energy, transportation and synthetic materials. North Korea had no oil reserves for making vinalon or powering its factories and Pyongyang depended on oil imports from the Soviet Union.

Even so, Kim Il-sung said North Korea must be independent.

“It may be cheaper and faster to produce the synthetic fiber using petro-chemistry ... But, constructing industries dependent on other countries’ raw materials is the same as having others grab you by the collar,” he said.

To help make its fabric of stone, the North wanted nuclear power. For years, it asked its Soviet allies to help with generation facilities. It only secured one nuclear power station.

In 1967, vinalon inventor Ri was made head of the Atomic Energy Research Institute in Yongbyon. Today, this houses the North’s light water nuclear reactor.

In 1973, Kim Dong-gyu, a high-ranking North Korean official, told Romanian leader Nicolai Ceaucescu that North Korea was producing “70 to 80 tonnes” of vinalon, and finding that hard to increase.

“Presently we are struggling to increase production in vinalon factories up to 50,000 tonnes per year,” he said.

The Hamhung facility was expanded so it could make more calcium carbide, the coal and limestone compound on which vinalon is based. Soviet economies were driven by targets laid down in plans rather than the laws of supply and demand.

Calcium carbide can be used to make many things. Defectors from Hamhung told reporters that it was thought to make chemical weapons — a claim others have also made and which is technically possible, but which no one has proven.

“Every factory in North Korea, whatever factory that would be ... had divisions for the Second Economy,” said Lee Min-bok, 60, who worked as a researcher at the Academy of Agricultural Science and visited the first vinalon factory. “People in North Korea call the war industry the Second Economy. The first economy is called the People’s Economy.”

More recently, Western arms experts at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies have suggested that the vinalon plant might be used to help produce rocket fuel for missile tests.

Scientists have said this is also technically possible, but unproven.

As North Korea built up its military, its debts increased. It eventually owed a total of US$11 billion to Moscow, most of which Russia was to write off in 2012. The North also accumulated debts in the West. They went unpaid year after year, totaling about US$770 million in the 1970s.

Soviet support was declining and China’s new paramount leader, Deng, was introducing market principles. He signed agreements on trade with North Korea in 1982.

North Korea started building a second vinalon factory in Sunchon in 1983 to achieve “a target 1.5 billion meters of cloth.”

The factory was to be the biggest chemical industrial complex in the country and to be controlled by the military. Kim Il-sung’s talk of running it on oxygen never materialized. Despite the reported US$10 billion investment, the complex was never fully completed.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, North Korea lost all its Soviet funding. Chinese imports entered ordinary North Koreans’ lives.

China has exported hundreds of thousands of tons of textiles and clothing to North Korea, customs data show.

“In the 1990s, North Koreans relied mostly on Chinese fabric for their clothes. Since then, enormous amounts of Chinese fabric have been imported into North Korea,” said Choi Goog-jin, a South Korean entrepreneur who tried to import North Korean vinalon in 2011.

CAPITALISM AT NIGHT

On July 8, 1994, Kim Il-sung died from a heart attack. His son Kim Jong-il took over, but within a year, Pyongyang was forced to ask international humanitarian agencies for aid.

Hamhung was hit by a flood and received no coal. It suspended fiber production. There was no work.

Residents from Hamhung said that vinalon became the basis of an exchange scheme to survive.

It was a similar story across the country.

Famine killed as many as 3 million North Koreans. North Koreans still call those years the “Arduous March,” a term introduced by the official media to stir the starving.

Defectors have said that people took machine parts, as well as pure nickel and copper from wires and pipes, to informal markets.

“People ripped machines into metal parts from the vinalon factory, smuggled and sold them ... some of them were publicly executed... Production lines stopped rolling ... workers starved to death,” said Jeong Jin-hwa, 53, who defected to the South in 1999.

By 1996, when Ri died, even party cadres loyal to the socialist system had turned to trading — a form of capitalist “self-reliance.”

In 2001, Choi created a company, Korea Vinylon Co, to import North Korean vinalon. After one year of sample tests and negotiations, the business failed.

“Vinalon does not have competitiveness in clothing,” Choi said. “If you look at vinalon suits in North Korea, they are rough and heavy.”

In 2002, in Onsong County, North Korea, a high-school student also called Choi said he had bought a fake Adidas T-shirt and short pants from a market. The blue clothes were made of vinalon.

“I wore that fake Adidas kit until I came here,” said Choi, now 30, who defected to the South in 2006. “The color did not change. It was quite sturdy.”

“We have this expression — socialism during the day and capitalism at night,” Choi said. “That is, politically and what is seen on surface is socialism, but beneath the surface, everything people do is capitalist.”

VINALON VICTORY

In 2010, Kim Jong-il reopened the February 8 Vinalon Complex.

“This is an extra-big event, as important as launching a new type A-bomb, and represents a great victory of socialism,” he said.

The next year, he died suddenly on his private train. His son Kim Jong-un took over as North Korean leader and in 2012 introduced economic changes, including turning a blind eye to the informal markets.

There was demand for vinalon — in those private markets.

Jung Min-woo, 29, served as a military officer before leaving North Korea in 2013. He said that some ranking military officers bought custom-made shiny vinalon uniforms from private markets to look cool.

“Many ranking officers wear them... but they are not good for war,” Jung said. “If war breaks out, lots of sparks and bullets go back and forth... Cotton tends to melt and vanish, but vinalon burns you because it sticks to your skin.”

Choi Goog-jin agreed.

“The uniforms made of vinalon are not suitable for combat,” he said. “When it rains, the uniforms soak up water and become very heavy, which inevitably makes it difficult for soldiers to move. After a while, the uniforms turn very stiff.”

By now, instead of producing vinalon, many North Koreans made clothes for China.

Kang Eung-chan, who defected in 2013, said he hired 40 local seamstresses and used imported fabrics — including nylon — to make jumpers for Chinese customers.

He paid locals US$40 to US$50 a month, he said.

“Who wears vinalon now? Almost no one,” Kang said.

Even so, North Korea has said it still produces the fiber. In last year’s New Year’s speech, Kim Jong-un laid out a plan to revamp the vinalon complex.

“This sector should revitalize production at the February 8 Vinalon Complex, expand the capacity of other major chemical factories and transform their technical processes in our own way,” he said.

If the new leader manages to drive North Korea’s vinalon output with as much vigor as its missile tests, the fabric made of stone might yet find a new lease of life.

Additional reporting by Yeom Seung-woo, Yang Heek-yong and Park Min-woo

The saga of Sarah Dzafce, the disgraced former Miss Finland, is far more significant than a mere beauty pageant controversy. It serves as a potent and painful contemporary lesson in global cultural ethics and the absolute necessity of racial respect. Her public career was instantly pulverized not by a lapse in judgement, but by a deliberate act of racial hostility, the flames of which swiftly encircled the globe. The offensive action was simple, yet profoundly provocative: a 15-second video in which Dzafce performed the infamous “slanted eyes” gesture — a crude, historically loaded caricature of East Asian features used in Western

Is a new foreign partner for Taiwan emerging in the Middle East? Last week, Taiwanese media reported that Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) secretly visited Israel, a country with whom Taiwan has long shared unofficial relations but which has approached those relations cautiously. In the wake of China’s implicit but clear support for Hamas and Iran in the wake of the October 2023 assault on Israel, Jerusalem’s calculus may be changing. Both small countries facing literal existential threats, Israel and Taiwan have much to gain from closer ties. In his recent op-ed for the Washington Post, President William

A stabbing attack inside and near two busy Taipei MRT stations on Friday evening shocked the nation and made headlines in many foreign and local news media, as such indiscriminate attacks are rare in Taiwan. Four people died, including the 27-year-old suspect, and 11 people sustained injuries. At Taipei Main Station, the suspect threw smoke grenades near two exits and fatally stabbed one person who tried to stop him. He later made his way to Eslite Spectrum Nanxi department store near Zhongshan MRT Station, where he threw more smoke grenades and fatally stabbed a person on a scooter by the roadside.

Taiwan-India relations appear to have been put on the back burner this year, including on Taiwan’s side. Geopolitical pressures have compelled both countries to recalibrate their priorities, even as their core security challenges remain unchanged. However, what is striking is the visible decline in the attention India once received from Taiwan. The absence of the annual Diwali celebrations for the Indian community and the lack of a commemoration marking the 30-year anniversary of the representative offices, the India Taipei Association and the Taipei Economic and Cultural Center, speak volumes and raise serious questions about whether Taiwan still has a coherent India