More than 70 aging women live in a squalid neighborhood between the rear gate of the US Army garrison, and half a dozen seedy nightclubs in Pyeongtaek, South Korea. Near the front gate, glossy illustrations posted in real-estate offices show the dream homes that might one day replace their one-room shacks.

They once worked as prostitutes for US soldiers in this “camptown” near Camp Humphreys, and they have stayed because they have nowhere else to go. Now, the women are being forced out of the Anjeong-ri neighborhood by developers and landlords eager to build on prime real estate around the soon-to-be-expanded garrison.

“My landlord wants me to leave, but my legs hurt, I can’t walk and South Korean real estate is too expensive,” says Cho Myung-ja, 75, a former prostitute who receives monthly court eviction notices at her home, which she has rarely left over the past five years because of leg pain.

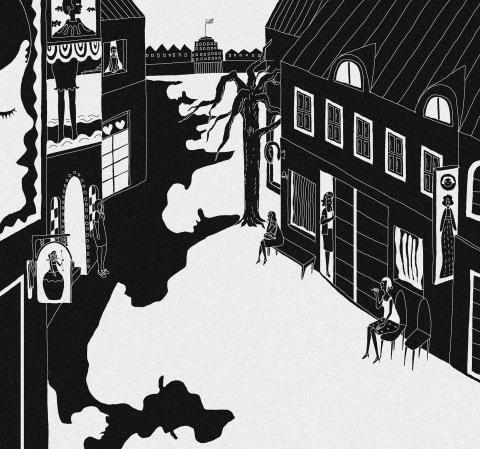

Illustration: Mountain People

“I feel like I’m suffocating,” she says.

Plagued by disease, poverty and stigma, the women have little to no support from the public or the South Korean government.

Their fate contrasts greatly with a group of South Korean women forced into sexual slavery by Japanese troops during World War II. Those so-called “comfort women” receive government assistance under a special law, and large crowds demanding that Japan compensate and apologize to the women attend weekly rallies outside the Japanese embassy.

While the camptown women receive social welfare, there is no similar law for special funds to help them, according to two Pyeongtaek city officials who refused to be named because of office rules.

Many people in South Korea do not even know about the camptown women.

In the decades following the devastation of the 1950-1953 Korean War, South Korea was a poor dictatorship deeply dependent on the US military.

Analysts say the South Korean government saw the women as necessary for the thousands of US soldiers stationed in the South.

Some of the women went to the camps voluntarily; others were brought by pimps.

In 1962, the government formalized the camptowns as “special tourism districts” with legalized prostitution. That year, about 20,000 registered prostitutes worked in nearly 100 camptowns, and many more were unregistered.

The women who became prostitutes saw few other options, but the work made them social pariahs, unable to live or work anywhere else, says Park Kyung-soo, secretary general of the National Campaign for the Eradication of Crimes against Korean Civilians, a group that tries to uncover and monitor alleged US military crimes against South Koreans.

Pockets of former camptown women exist throughout South Korea. Now in their 60s, 70s and 80s, the women of Anjeong-ri mostly live alone in tiny homes, struggling to pay for food and rent on a monthly government stipend of between 300,000 and 400,000 won (US$300 and US$400).

Activists say most of the women are in danger of losing their homes.

“I’m so worried that I can’t sleep,” says a camptown woman who will only give her surname, Kim, because she is ashamed of her past.

The 75-year-old’s landlords have told her she has a month to leave, and she looks nearly every day for a new home.

The camptown women’s predicament began when Washington and Seoul agreed in 2004 to relocate the sprawling Yongsan US base, which takes up 251 hectares of prime real estate in the center of wealthy Seoul, to the base in Pyeongtaek, 70km from the capital. The deadline, originally set for 2012, is now tentatively 2016.

At the end of the move, Camp Humphreys will have tripled in size and house more than 36,000 people, including troops, their family members and civilian staff. Investors are eyeing the Pyeongtaek land in anticipation of homes for US military families and sites for businesses that will cater to the new flood of people and wealth.

Piles of rubble from demolished homes sit next to new villas. A few blocks from some of the remaining shacks, a partially built apartment building rises to the beating of hammers and whirring of drills.

Landlords eager to capitalize on rising land prices are trying to force the women out with pressure and eviction orders, and have more than quadrupled the monthly rent, from 50,000 won to 200,000 won, said Woo Soon-duk, director of the Sunlit Sisters’ Center, a local non-governmental organization dedicated to the women.

Many of the women want the government to take greater responsibility for their well-being and financial stability. They believe they played an important role for South Korea.

In June, 122 former camptown prostitutes sued the South Korean government. They are each seeking 10 million won in compensation. A court date has not been set.

Activists and lawyers for the women say police prevented prostitutes from leaving; that the government forced the women to undergo tests for sexually transmitted diseases, then locked them up if they were sick; and that officials from the US military and South Korean government regularly inspected the prostitution operations.

The government saw the camptowns as a way to regulate prostitution, bring in much-needed money and keep the US soldiers happy.

It was also worried about a rising number of sex crimes committed against South Korean women by US soldiers in the 1950s and 1960s, Park says.

A spokeswoman for the South Korean Ministry of Gender Equality and Family declined to comment until after a court reaches a decision.

She would not give her name, saying office rules prohibited her from being named publicly.

The US military would not answer specific questions about the women, saying in a statement that it was aware of their case and has “zero tolerance” for prostitution.

Many of the women feel trapped.

As Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers’ Rebels plays on an old radio, Kim Soon-hee, 65, a former camptown prostitute, eats a piece of melon. Clotheslines crisscross her room, which barely fits a bed and a dresser. The air smells strongly of the mold that covers the walls.

She wants to move to a better place in the same neighborhood, but she is too poor.

“In the winter, the water doesn’t flow because the pipes are frozen,” she says.

She shares a courtyard with two other one-bedroom homes, which are empty.

Jang Young-mi, 67, who was orphaned as a girl and worked in a military camptown for nearly two decades, lives with three mangy dogs. A bite from one of them left the long white scar on her hand, but she refuses to abandon the offending animal.

“Maybe because I lived for so long with American soldiers, I can’t fit in with Koreans,” Jang says. “Why did my life have to turn out this way?”

There is a modern roadway stretching from central Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland in the Horn of Africa, to the partially recognized state’s Egal International Airport. Emblazoned on a gold plaque marking the road’s inauguration in July last year, just below the flags of Somaliland and the Republic of China (ROC), is the road’s official name: “Taiwan Avenue.” The first phase of construction of the upgraded road, with new sidewalks and a modern drainage system to reduce flooding, was 70 percent funded by Taipei, which contributed US$1.85 million. That is a relatively modest sum for the effect on international perception, and

At the end of last year, a diplomatic development with consequences reaching well beyond the regional level emerged. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared Israel’s recognition of Somaliland as a sovereign state, paving the way for political, economic and strategic cooperation with the African nation. The diplomatic breakthrough yields, above all, substantial and tangible benefits for the two countries, enhancing Somaliland’s international posture, with a state prepared to champion its bid for broader legitimacy. With Israel’s support, Somaliland might also benefit from the expertise of Israeli companies in fields such as mineral exploration and water management, as underscored by Israeli Minister of

When former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) first took office in 2016, she set ambitious goals for remaking the energy mix in Taiwan. At the core of this effort was a significant expansion of the percentage of renewable energy generated to keep pace with growing domestic and global demands to reduce emissions. This effort met with broad bipartisan support as all three major parties placed expanding renewable energy at the center of their energy platforms. However, over the past several years partisanship has become a major headwind in realizing a set of energy goals that all three parties profess to want. Tsai

On Sunday, elite free solo climber Alex Honnold — famous worldwide for scaling sheer rock faces without ropes — climbed Taipei 101, once the world’s tallest building and still the most recognizable symbol of Taiwan’s modern identity. Widespread media coverage not only promoted Taiwan, but also saw the Republic of China (ROC) flag fluttering beside the building, breaking through China’s political constraints on Taiwan. That visual impact did not happen by accident. Credit belongs to Taipei 101 chairwoman Janet Chia (賈永婕), who reportedly took the extra step of replacing surrounding flags with the ROC flag ahead of the climb. Just