In the summer of 1914 the Austrian novelist Stefan Zweig was on holiday in Ostend with fellow writers and artists. One afternoon, noticing the sudden appearance of uniformed soldiers on the promenade, they buttonholed an officer: “Why all this stupid marching around?” It was Aug. 3: War was less than 24 hours away, but it seemed impossible.

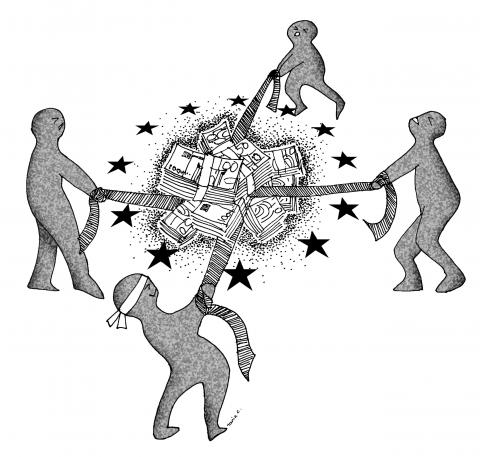

Believing the era of peace, social liberalism and globalized trade could never end, the European elite walked blindly into its ending. Today the political elites of Europe stand in danger once again of destroying a dream. They have convinced themselves that the single currency and the EU are the same project, and that the collapse of either would be the end of the world they know. Therefore it cannot happen. This fallacy is about to be put to the test.

Greece hovers on the brink of a debt default; the cost of borrowing for Germany is shooting up; the cobblestones of Spanish towns echo to mass protests against austerity; a thousand people a week leave Ireland and across northern Europe rightwing parties drum their fingers in anticipation of one day, soon, obtaining if not power then the balance of it.

What is at stake this summer is more than just the future of the eurozone, for which there are predictable outcomes. It is the future of pan-European solidarity, which has been implicit in the project of the EU and, recently, in short supply.

In the strict sense “solidarity” is something which, in the EU, concerns mutual defense: in the Lisbon treaty it applies not just against military aggression or terrorist attack, but also in the case of “natural and man-made” disasters. However, the concept of solidarity between the peoples, states and classes of Europe is older than the document signed in Lisbon. It stretches back to June 16 1940, when — at the urging of Jean Monnet — the British war Cabinet offered the French people common citizenship, merged foreign, defense, financial and economic policies and federated parliaments.

Out of the allied victory, the Marshall Plan and — four decades later — the rapid incorporation of Eastern Europe grew not just the institutions of trans-European solidarity, but an implicit social deal.

Europe would be a social market economy: there would be a safety net for the poor and cross-border wealth redistribution through the Social Fund. Eastern Europe would adopt the market, but limit the amount of organized crime and corruption to levels commensurate with those in the West. The former dictatorships of Greece, Portugal and Spain would shower social benefits on their populations in return for a gigantic act of forgetting who had done what to whom. Northern Europe would pay for it all and — by way of quid pro quo — drench its blond chest hairs with sunscreen on the beaches of the Mediterranean.

It is this deal that is falling apart.

Since the Greek fiscal crisis erupted in January last year, the combined forces of the European Central Bank (ECB), Economic and Financial Affairs Council (ECOFIN) and the European Commission have proved incapable of designing a resilient anti-crisis strategy. Only under pressure from the US government and the IMF did they come up, in May last year, with the 700 billion euro Financial Stability Mechanism, but its effectiveness was immediately undermined: first by the stark numerical fact that it was not big enough; second by the nonexistence of a leadership able to use the 700 billion euros to pre-empt crisis.

So now, 18 months after northern European voters were promised tough new conditions would be imposed on the feckless south, they are seeing the prospect of 350 billion in taxpayer euros being transferred to the periphery so that it can avoid social breakdown.

Under pressure from their own electorates, the governments of Finland, Germany and the Netherlands urge even more austerity. France urges a sell-off of prime assets (to be purchased by the Chinese — work out the realpolitik in that).

Meanwhile the IMF, the one body whose credibility had risen during the crisis, and whose leader was engaged in trying to mitigate austerity demands that would drive Greece, Portugal and Ireland into a deflationary spiral, is rendered suddenly leaderless. This allows the European elites, never happy confronting the crucial issues, to spend time bickering publicly about which European is next in line to run the IMF, barely acknowledging the conflict of interest involved.

While this plays out as economics in the broadsheet papers and across the crisp linen of Europe’s conference hotels — in the tabloids and on the streets it becomes politics, and politics is increasingly polarized: a 20 percent hard left bloc in the Portuguese parliament is balanced by the 19 percent gained by Timo Soini’s True Finns in last month’s elections. A slew of leftwing nationalists and independents in the Irish Dail are mirrored by the racist militias intimidating the Roma communities of Hungary.

Worse, the political response has begun to fragment on generational lines. Among older, organized workers from Athens to Lisbon you find a determination to resist in the old way, combined with the knowledge that no level of austerity can remove assets and social benefits accumulated over 20 years.

“We don’t do social explosions,” one Greek docker told me, casting a wry eye at the inflammatory headlines in communist newspapers plastered across the canteen wall.

For the youth it is different. The young people who’ve painted their faces and protested, camped and danced in the squares of Spain this month are explicitly rejecting the old politics: not just of the center, but also of the old left

The European political class insists a new bailout should be imposed on Greece only at the price of the same austerity that made the old bailout fail. It calls for asset sales at knockdown prices: a brilliant deal for the purchasers, but the worst possible deal for those trying to plug the hole in Greece’s finances, and it denies any possibility of a partial default. The bond markets, meanwhile, are certain it will happen; they ramp up the cost of borrowing accordingly, not just for Greece, but now also for Germany.

In October 2008, and again in the spring of 2009, the US authorities were able to find a circuit breaker for the financial crisis, in the shape of the Troubled Asset Relief Program and quantitative easing. Europe, unwilling to impose losses on its banks, indeed prepared to rubber-stamp stress tests on banks that then went bust, has yet to find a circuit breaker.

As a result, the combined momentum of fiscal crisis and social unrest could drag the periphery further into crisis and, in the case of Greece, out of the euro altogether.

None of the options are palatable: a serious default by the periphery would hammer banks and pension funds in the northern European core. A modern Marshall Plan for Ireland and South Europe would last years, cost hundreds of billions of euros, and with the US itself in debt reduction mode, only China and a reformed IMF could conceivably fund it. Leaving the euro would not solve the basic problems of competitiveness and unfunded social benefits in the south, but these are the options: as real as the “Error Del Sistema” placards in Madrid’s Campo Real.

Looking back on the summer of 1914 Zweig wrote: “The worst of it was, the very thing we loved the most, our common optimism, betrayed us; for everyone thought everyone else would back down at the last minute and so the diplomats began their game of mutual bluff.”

Common optimism is a value worth preserving; but so are realism and decisive action.

Paul Mason is economics editor of BBC television’s Newsnight.

There is much evidence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is sending soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and is learning lessons for a future war against Taiwan. Until now, the CCP has claimed that they have not sent PLA personnel to support Russian aggression. On 18 April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelinskiy announced that the CCP is supplying war supplies such as gunpowder, artillery, and weapons subcomponents to Russia. When Zelinskiy announced on 9 April that the Ukrainian Army had captured two Chinese nationals fighting with Russians on the front line with details

Within Taiwan’s education system exists a long-standing and deep-rooted culture of falsification. In the past month, a large number of “ghost signatures” — signatures using the names of deceased people — appeared on recall petitions submitted by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) against Democratic Progressive Party legislators Rosalia Wu (吳思瑤) and Wu Pei-yi (吳沛憶). An investigation revealed a high degree of overlap between the deceased signatories and the KMT’s membership roster. It also showed that documents had been forged. However, that culture of cheating and fabrication did not just appear out of thin air — it is linked to the

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), joined by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), held a protest on Saturday on Ketagalan Boulevard in Taipei. They were essentially standing for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which is anxious about the mass recall campaign against KMT legislators. President William Lai (賴清德) said that if the opposition parties truly wanted to fight dictatorship, they should do so in Tiananmen Square — and at the very least, refrain from groveling to Chinese officials during their visits to China, alluding to meetings between KMT members and Chinese authorities. Now that China has been defined as a foreign hostile force,

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to