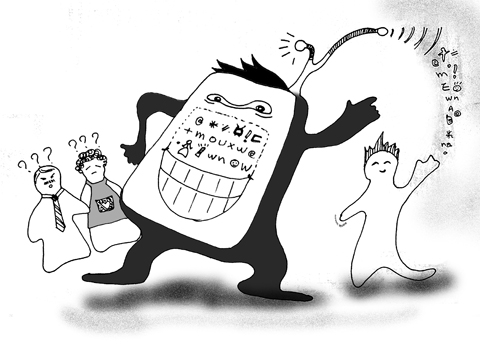

The Philippines is wrestling with what authorities say is a language monster invading youth-speak in Internet social networks and mobile phone text messaging.

The phenomenon has triggered enormous social debate, with the government declaring an “all out war” against the cyber-dialect, called jejemon, but the Catholic Church defending it as a form of free expression.

The word jejemon is derived from jeje as a substitute for “hehe” — the SMS term for laughter — and then affixing it with mon — taken from the popular Japanese anime of cute trainable monsters called Pokemon.

Education Secretary Mona Valisno believes it could blunt the Philippines’ edge in English proficiency, which has long helped the impoverished country attract foreign investment and sustain its lucrative outsourcing industry.

“Texting or using wrong English and wrong spelling could be very bad,” Valisno told reporters recently as she declared her war on jejemon, urging teachers and parents to encourage the nation’s youth to use correct English. “What I am concerned about is the right construction, grammar. This is for their own improvement, for them to be able to land good jobs in the future.”

Jejemon emerged over the past year as young people tried to shorten text messages on mobile phones, language experts say.

It then morphed into a unique language that spawned new words and phrases by deliberately stringing together misspelled words without syntax and liberally sprinkling them with punctuation marks.

And the initial idea of tighter texting got lost as many “words” became longer than the originals.

Instead of spelling “hello” for example, jejemon users spell it as “HeLouWH” or “Eowwwh,” while the expression “oh, please” becomes “eoowHh ... puhLeaZZ.”

Or, throwing a bit of the local language Tagalog into the mix, you can tell your significant other “lAbqCkyOuHh” (I love you) or “iMiszqcKyuH” (I miss you), and convey that you’re happy by texting “jAjaja” or “jeJejE.”

There are however no hard and fast rules in the constantly evolving jejemon, which perhaps adds to its appeal for teens and the bewilderment of adults.

The jejemon craze quickly spread among the country’s more than 50 million mobile phone subscribers, who send a world-leading average of up to 12 text messages each every day, according to industry and government figures.

It then found its way among Filipinos in social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter.

For Manila high school student Laudemer Pojas, jejemon is an important part of his lifestyle that allows him to talk with friends using coded messages beyond the grasp of his strict parents.

“I am a jejemon addict,” the portly 17-year-old Pojas said. “I don’t know what the big fuss is all about. It’s orig [unique] to people my age, like street lingo but on the net and texting. It’s also easier to do and can’t be read by my parents who check my cel [mobile phone] from time to time.”

He said he met many new friends on Facebook after he joined a site defending jejemon from the jejebusters — or those who hate the language.

Gary Mariano, a professor at Manila’s De La Salle University and an expert in new media, said he had mixed feelings about jejemon.

“I’m torn between efficiency and formal correctness,” Mariano said, pointing out jejemon was borne out of people simply adapting to a digital lifestyle. “I require my students to use formal language in school papers, but when it comes to ordinary e-mails or text messages, I can be more tolerant. There should be no shame in using shortcuts in Internet language, but for the young ones who have not been exposed to proper English, then jejemon will not give them that foundation.”

He noted that languages had always evolved, with many of the world’s tongues constantly borrowing from one another.

“Even in modern English, there is still a debate on which is better, the one spoken by the British or the Americans,” he said. “The history of language has been full of transitions.”

Mariano said he used jejemon, albeit sparingly, and that he knew of many English grammar teachers who had taken to it.

English was first introduced to the archipelago more than a century ago when the US brought in teachers to tutor the locals at the end of its war with Spain in 1898.

By the time full independence was gained in the mid-1940s, English was so widely spoken it subsequently became the medium of instruction in all schools and the unofficial second language next to Filipino.

But educators in recent years have lamented that spoken and written English appears to have deteriorated among the more than 90 million Filipinos.

One key indicator is that outsourcing firms that once relied on the pool of US-sounding Filipinos have recently reported a drop in recruitment.

This has forced the government to allocate more funds to upgrade English proficiency skills among teachers — which education secretary Valisno warned would be imperiled if the jejemon phenomenon was not stopped.

However, jejemon advocates have found an unlikely ally in the influential Roman Catholic Church, whose position on key social issues shapes public opinion.

It said jejemon was a form of free expression, comparing it to the language of hippies decades ago.

“Language is merely an expression of experience,” said Joel Baylon, who heads the Catholic Bishop’s Conference of the Philippines’ commission on youth. “What is more important are the values behind the language.”

Donald Trump’s return to the White House has offered Taiwan a paradoxical mix of reassurance and risk. Trump’s visceral hostility toward China could reinforce deterrence in the Taiwan Strait. Yet his disdain for alliances and penchant for transactional bargaining threaten to erode what Taiwan needs most: a reliable US commitment. Taiwan’s security depends less on US power than on US reliability, but Trump is undermining the latter. Deterrence without credibility is a hollow shield. Trump’s China policy in his second term has oscillated wildly between confrontation and conciliation. One day, he threatens Beijing with “massive” tariffs and calls China America’s “greatest geopolitical

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairwoman Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) made the astonishing assertion during an interview with Germany’s Deutsche Welle, published on Friday last week, that Russian President Vladimir Putin is not a dictator. She also essentially absolved Putin of blame for initiating the war in Ukraine. Commentators have since listed the reasons that Cheng’s assertion was not only absurd, but bordered on dangerous. Her claim is certainly absurd to the extent that there is no need to discuss the substance of it: It would be far more useful to assess what drove her to make the point and stick so

The central bank has launched a redesign of the New Taiwan dollar banknotes, prompting questions from Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — “Are we not promoting digital payments? Why spend NT$5 billion on a redesign?” Many assume that cash will disappear in the digital age, but they forget that it represents the ultimate trust in the system. Banknotes do not become obsolete, they do not crash, they cannot be frozen and they leave no record of transactions. They remain the cleanest means of exchange in a free society. In a fully digitized world, every purchase, donation and action leaves behind data.

Yesterday, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), once the dominant political party in Taiwan and the historic bearer of Chinese republicanism, officially crowned Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) as its chairwoman. A former advocate for Taiwanese independence turned Beijing-leaning firebrand, Cheng represents the KMT’s latest metamorphosis — not toward modernity, moderation or vision, but toward denial, distortion and decline. In an interview with Deutsche Welle that has now gone viral, Cheng declared with an unsettling confidence that Russian President Vladimir Putin is “not a dictator,” but rather a “democratically elected leader.” She went on to lecture the German journalist that Russia had been “democratized