Oct. 1 to Oct. 7

Kuo Pai-nian (郭百年) and his fellow Han Chinese settlers were locked in a stalemate with the Aboriginal warriors of Shuishalian (水沙連, the area around today’s Puli Township) for over a month until they decided to revert to trickery. Kuo offered to leave the area in exchange for deer antlers. When the Aboriginal men went to hunt for the antlers, Kuo and his cohorts invaded the village, burning, slaughtering and stealing. They even overturned all of the community’s graves and took the weapons inside to bolster their forces. The Aborigines had no choice but to flee. This was the beginning of the Kuo Pai-nian Incident of 1814.

As Chung You-lan (鍾幼蘭) shows in a study, Pingpu Peoples and the Puli Basin (平埔族群與埔里盆地), such instances of Han Chinese brutality toward Aborigines were not uncommon, and that the incident was a microcosm of the way in which Han Chinese violently expanded into Aboriginal territory. This expansion would in turn cause the affected Aboriginal group to encroach on the land of others.

Photo: Chen Feng-li, Taipei Times

What makes this incident unique, however, is that despite Kuo’s success in driving out the area’s inhabitants, the result of this conflict was not Han Chinese domination, but a mass migration of Aboriginal groups from the west coast into Puli. Many of whose descendants still live there today.

BLOOD IN THE MOUNTAINS

Chung writes that various Aboriginal groups lived in Shuishalian during the 17th and 18th centuries, but the exact ethnic composition isn’t clear because Han Chinese and even the coastal Siraya Aborigines were unable to enter the area.

Photo: Tung Chen-kuo, Taipei Times

At the turn of the 19th century, the Puli basin, which was a part of Shuishalian, was still considered an “untouched paradise” by the Han Chinese settlers of the western plains of Taiwan. In fact, the Qing Empire forbade Han Chinese to enter these mountain areas, and employed shou (熟) — “civilized” Aborigines who lived on the plains and largely cooperated with the Qing and had a high degree of contact with Han Chinese — to guard the border. The ones beyond the border were sheng (生), “uncivilized” Aborigines who were often hostile. This policy officially began in 1791.

However, since these “civilized” guards often did not farm land close to the border, they would rent it to Han settlers, who then became aware of the valuable land controlled by the “uncivilized” Aborigines. Consequently, illegal border crossings were common.

Additionally, the Qing court awarded Shuishalian Aborigines border guard positions because they had helped pacify an earlier Han Chinese rebellion.

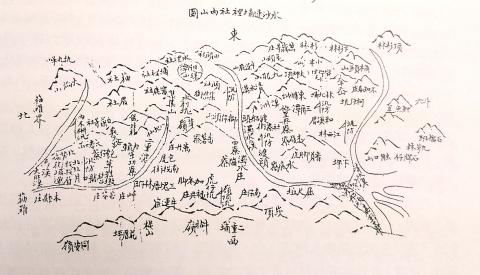

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

By 1800, the Han Chinese settlers around today’s Changhua County were running out of land to cultivate; newcomers could only look towards the mountainous area to the east. So when a Shuishalian border guard approached Kuo and told him that his community had valuable land to farm, they devised a plan to obtain a permit from Qing officials to cultivate it. The pair applied for and received the permit in the name of a dead local chief, claiming that he wanted to rent the land to Han Chinese settlers.

Using this permit, Kuo and about 1,000 followers entered the area and immediately started encroaching on Aboriginal land, farming way beyond what they were allowed to.

Finally, Kuo and company pushed their way towards today’s Puli. The Aborigines there were powerful enough to resist him, leading to the stalemate that finally ended with the massacre.

Qing officials in Tainan sent agents to investigate, but Kuo bribed them off. It was only a matter of time, however, before officials caught on, immediately revoking his permit, sentencing him to a beating, evicting all Han Chinese and threatening to decapitate any non-Aborigines who dared to enter the area. It was clear that officials not only wanted to avoid any conflict with the Aborigines, but were also concerned that Han Chinese rebellions would be harder to quell if they gained access to the rugged mountains.

PINGPU MIGRATION

While the Puli Aborigines were now free to return home, they were greatly weakened by the ordeal. This not only rendered them vulnerable to encroachment from the west, they also suffered attacks by Atayal tribes from the north.

In January 1823, they invited Pingpu settlers from the west coast, who were also facing pressure from the ever-increasing numbers of Han Chinese, to move to Puli to farm and help defend the territory. This was a highly organized migration as the two sides signed agreements and the newcomers had to give presents to the original inhabitants upon arrival. This process took place in several waves over the next few decades.

There were some Han Chinese who pretended to be Aborigines and took Aboriginal names so as to settle in the area. Records show, however, that the numbers remained low for a few decades.

Ironically, the influx of Pingpu settlers — whether legally or illegally — eventually led to the demise of the original inhabitants, who were either assimilated or pushed out. By 1847, Qing records show there were more than 2,000 immigrant Aborigines in Puli compared to 150 or so natives. A Japanese survey in 1900 shows that only eight remained, with their mother tongue completely lost.

Meanwhile, the Qing realized that they could not stop Han Chinese from illegally crossing the borders as arable land became increasingly scarce, and abolished the demarcations in 1875. In 1887, the Qing set up an Aboriginal affairs office in Puli, officially taking the area under control. Just eight years later, the Qing ceded Taiwan to Japan.

Today, the descendants of these settlers trace their lineage back to six tribes who are fighting for recognition today: Taokas, Pazeh, Kahabu, Papora, Babuza and Hoanya.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name