Taiwan in Time: Dec. 5 to Dec. 11

Shortly after noon on Dec. 10, 1949, Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) and his son Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) finished their last meal in China. The elder Chiang’s mood was solemn as they headed to Chengdu’s military airport. Without saying a word, he boarded the plane to Taiwan.

By that time, the transfer of people, public property and military and governmental institutions to Taiwan was mostly complete. A day earlier, the Republic of China’s Executive Yuan held its 102nd meeting — its first in Taipei.

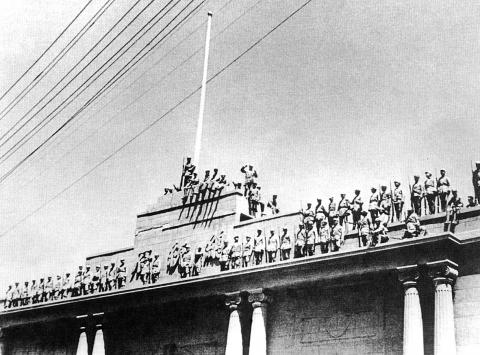

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) retreat to Taiwan in 1949 after losing the Chinese Civil War was a lengthier and more monumental, taking place over the course of more than a year with countless freight and air trips.

Before deciding on Taiwan, the KMT entertained the idea of retreating to western China. Many officials opposed the move, as it was too close to the rapidly advancing People’s Liberation Army, which knew the terrain well.

Chen Chin-chang (陳錦昌) writes in his book Chiang Kai-shek’s Retreat to Taiwan (蔣中正遷台記) that the decision to retreat to Taiwan was suggested by geographer and future Chinese Cultural University founder Chang Chi-yun (張其昀) in 1948.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Chang argued that Taiwan’s subtropical climate, abundant resources and advanced infrastructure left behind by the Japanese would be able to support a massive population influx. The Taiwan Strait would make it difficult for the People’s Liberation Army to mount an immediate attack, and the US would be more likely to protect such a strategic location.

Chang also believed that the people of Taiwan would welcome the “motherland” government after years of Japanese rule, and that it was relatively free of communist influence. The suppression of the 228 Incident a year previously would further deter people from causing unrest, making it a “stable” base for the KMT to prepare their counterattack.

THE BIG MOVE

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Chiang favored Chang’s proposal. Starting in August 1948, the Air Force started moving its equipment and institutions to Taiwan. This operation alone was a massive one. It took what is today the Air Force Institute of Technology 80 flights and three ships over four months to relocate. This did not include the other academies, training facilities, manufacturing plants, radio stations and military hospitals, which moved separately.

Chen writes that during this period, an average of 50 or 60 planes flew daily between Taiwan and China transporting fuel and ammunition.

By May 1949, the Air Force Command Headquarters was operating out of Taipei, having transported 1,138 officers, 814 pilots, 2,600 family members and about 6,000 tonnes of equipment and classified documents. The last group of pilots barely made it out of Shanghai as the Communists stormed the airport. Other military branches made their exits as key locations in China fell.

The official decision to transport artifacts from the National Palace Museum, National Central Library and Academia Sinica’s Institute of History and Philology to Taiwan was made on Nov. 10, 1948, but Chen writes that about 600 museum items were already moved in March. The National Central Museum and Beijing Library later joined the operation, resulting in a total of 5,522 large crates, with the first batch leaving Shanghai on Dec. 21.

Chen writes that the Navy sailors transporting the third batch boarded the ship with family members upon hearing that it was bound for Taiwan, and refused to disembark, greatly decreasing the number of crates it could carry.

Of course, not all the items could be saved. For example, the roughly 230,000 National Palace Museum items constituted just above 20 percent of the entire collection. But Chen writes that these were carefully selected.

In addition to books and documents, Institute of History and Philology director Fu Si-nian (傅斯年) also spearheaded a rush to persuade scholars to flee to Taiwan.

Chiang Kai-shek ordered a secret operation to transport gold from the Central Bank to Taiwan on Nov. 30, 1948. In the middle of the night, 774 boxes full of gold were manually transported from the bank to the pier. These operations continued until May of the following year. One ship sank, resulting in a loss of US$60 million and bank staff, and another one was held hostage by officers who almost succeeded in fleeing with the money to South America.

Other items transported included radio stations, boats, factory machinery, cars, wood, cloth and so on. About 1,500 ships carrying these items departed from Shanghai alone.

The number of people who arrived in Taiwan from China during this time is disputed. Chen’s book states that nearly 500,000 civilians made the trip between 1948 and 1950 along with an additional 500,000 military personnel for a total of 1 million, but other estimates have gone as high as 2.5 million.

Meanwhile, the Nationalist government hung on, moving from Chongqing to Chengdu on Oct. 28, 1949. On Nov. 30, the Air Force was given 10 days to transport the remaining Nationalist officials and their family out of China. Chiang Kai-shek remained until the last minute, never to return.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

This is the year that the demographic crisis will begin to impact people’s lives. This will create pressures on treatment and hiring of foreigners. Regardless of whatever technological breakthroughs happen, the real value will come from digesting and productively applying existing technologies in new and creative ways. INTRODUCING BASIC SERVICES BREAKDOWNS At some point soon, we will begin to witness a breakdown in basic services. Initially, it will be limited and sporadic, but the frequency and newsworthiness of the incidents will only continue to accelerate dramatically in the coming years. Here in central Taiwan, many basic services are severely understaffed, and

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It is a soulful folk song, filled with feeling and history: A love-stricken young man tells God about his hopes and dreams of happiness. Generations of Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang region, have played it at parties and weddings. But today, if they download it, play it or share it online, they risk ending up in prison. Besh pede, a popular Uighur folk ballad, is among dozens of Uighur-language songs that have been deemed “problematic” by Xinjiang authorities, according to a recording of a meeting held by police and other local officials in the historic city of Kashgar in

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.