It was an unusual theatrical performance that took place on a recent Sunday in Erchongpu (二重埔), a Hakka farming village in Jhudong Township (竹東), Hsinchu County. A group of farmers , many in their 60s and 70s, tilled the land, planted seedlings and harvested in front of a large audience made up of activists, teachers, students and families as well as members from self-help organizations in Miaoli County’s Dapu Village (大埔), Puyu (璞玉) in Hsinchu County’s Jhubei Township (竹北) and other communities facing land expropriation by the government to make way for development projects.

These first-time actors were playing themselves. The performance was as much about portraying their rustic life as it was about giving a firsthand account of a long-running battle to protect the livelihood of farmers.

“I used to eat 25 bowls of rice a day so that I had the strength to farm the land. And you? What did you eat when you were growing up?” an 85-year-old farmer known as Uncle A-hsiang (阿祥伯) asks another farmer playing the role of a government official who informs local residents of the government’s plan to take over their land for a science park.

Photo: Ho Yi, Taipei Times and Center for Applied Theater, Taiwan

For the past four months, the Center for Applied Theater, Taiwan (台灣應用劇場發展中心) has been working with members of the Erchongpu Self-Help Organization (二重埔自救會) through a series of workshops designed to voice locals’ stories. The center’s director, Lai Shu-ya (賴淑雅), who has worked with remote villages and grassroots groups since 1996, said the idea behind the community-based theater projects is to encourage residents to express opinions and participate in local affairs and issues. The collaboration with Erchongpu, she added, is the theater group’s attempt to respond to land grabbing and related problems that have plagued the country’s farming communities.

Forced Land Expropriation

“It has been an important learning experience for me. They have taught me what theater for the people is all about … We should throw away theatrical methods and practices so that the true drama of local people’s lives can be revealed,” Lai said. “These farmers are tough, highly organized, disciplined and very close to each other.”

Photo: Ho Yi, Taipei Times and Center for Applied Theater, Taiwan

To Liu Ching-chang (劉慶昌), a member of the self-help organization and head of the Alliance for the Defense of Farming Villages (捍衛農鄉聯盟), the strength of their solidarity lies in the community’s long history of fighting against the forced takeover of farmland by the government.

In 1981, the Hsinchu County Government announced the expropriation project in the area to make way for the third-stage expansion of the Hsinchu Science Park. More than 1,000 protestors besieged the science park in 1989, led by the then-county councilor Lu Yuan-kuei (呂源貴).

“We blocked the main entrance, only allowing people to get out, but not get in. The main road in Hsinchu City and the highway were totally jammed,” the 79-year-old former councilor recalled.

Photo: Ho Yi, Taipei Times and Center for Applied Theater, Taiwan

Officials decided to abort the science park project in 2000 due to a lack of funds. “But they [the county government] didn’t tell us about the withdrawal,” said Lu Yuan-kuei, who has lived in Erchongpu all his life.

In 2006, the county government modified the development plan and used build–operate–transfer (BOT) to solve the financing problem. The renewed project involves building an industrial zone, commercial areas and housing complexes on more than 440 hectares of land requisitioned from Erchongpu, Sanchongpu (三重埔), Touchongpu (頭重埔) and Kehuli (科湖里).

Corruption

Photo: Ho Yi, Taipei Times and Center for Applied Theater, Taiwan

More than 120 farmers in Erchongpu and Sanchongpu quickly joined hands to question the legitimacy of the plan and vowed to stop it from being carried out.

Lu Cheng-sheng (呂正盛), a farmer from Sanchongpu, said only big corporations and corrupt politicians benefit from the deal.

“They are not even planning to build a science park. They want apartments built by big businesses. Taiwan has a very low food self-sufficiency rate. Why trade such good farmland for more buildings?” he added.

Blessed with natural springs used to irrigate crops all year around, Erchongpu is known for producing prime-quality rice. The famous Jhudong irrigation canals also started from here when, in 1926, local landlord Lin Chun-hsiu (林春秀) initiated the construction project that, once completed two years later, saw 21km of canals irrigating over 500 hectares of farmland.

“The Lin family was the biggest landlord back then, owning over 900 hectares of land. They sold some 400 hectares to fund the construction,” Lu Yuan-kuei said.

Nearly 90 years later, the canals continue to supply water to farmers in neighboring areas.

Chang Te-tsai (張德財), a 76-year-old farmer from neighboring Puyu, a farming village embroiled in a decade-long struggle against land grabbing by the government to build a high-tech industrial park, said people who don’t farm cannot understand the relationship between farmers and the land.

“Three generations of our family have lived here. We have built our family house three times, first with mud and dirt, then with concrete and brick,” Chang said. “When I started working in the paddy fields, I was too young to even lift a hoe … Our land is our life.”

“Land sharks”

While facing expropriations, the farming villages also have to confront the threat from real estate speculators and land investors. Thirty years after Erchongpu was included in the expropriation project, much of its land has fallen into the hands of outsiders hoping to make profits out of expropriations.

“Most old farmers don’t want to have their land taken over, but new landowners all want to sell their properties,” Lu Cheng-sheng said.

“You see those fallow fields where only vegetables or grass grow. They were bought by land sharks. Only those where you see rice growing belong to real farmers,” Liu Ching-chang explained.

To Liu Feng-ying (劉鳳英) from Sanchongpu, life over the past few years has been “painful.”

“Every morning I wake up, I worry what will become of us and where our three-generation family can go if the government tears down our house. My husband and I worked very hard to save money and build this house. You see what happened in Dapu. It can happen to us too,” she said, breaking into tears while recalling the incident in which the Miaoli County Government sent in excavators escorted by police to dig up rice paddies in Dapu in 2010.

The controversial development plan is currently under review by the Ministry of Interior’s Construction and Planning Agency. Once it is approved, the expropriation will begin.

Farmer Solidarity

The self-help organization said they will bring the case to the supreme administrative court if the plan is passed.

In the meantime, the farmers’ group takes an active role in closely monitoring the reviewing process, looking into the makeup of the review committees, preparing for their next move and training members to convey their opinions clearly and effectively when facing politicians and the media.

“You have to treat each battle as your last, because if you don’t, the next thing that will arrive at your door is likely to be a notification from the government telling you to take the money and leave,” Liu Ching-chang said. “We have to always be prepared.”

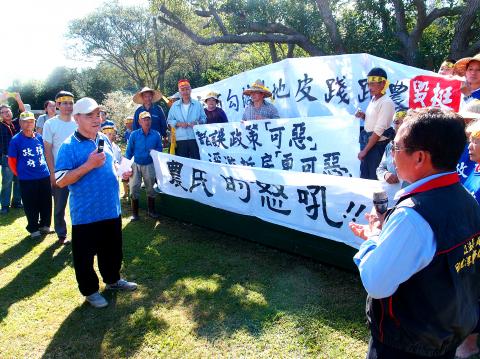

Liu and his fellow comrades have also sought alliance with other farmers facing a similar predicament, as well as farmers’ right activists, academics and students. Together, they have held large-scale demonstrations, staged overnight protests on Ketagalan Boulevard in front of the Presidential Office and drawn the public’s attention to “land justice.”

“In this lawless country where it is the government that breaks the law, we people need to unite to protect ourselves,” Liu Ching-chang said.

“Before, farmers didn’t know how to fight back. Many died heartbroken after losing their homes and land. Now, we are taking back our rights to work and live.”

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them