From hotels with segregated swimming pools to jelly made from seaweed instead of pig bones, majority-Buddhist Thailand is chasing halal gold as it welcomes Muslim visitors and touts its wares to the Muslim world.

Inside the cavernous dining hall of the five-star Al Meroz Hotel Bangkok in a Muslim suburb, an older man with a wispy beard recites verses of the Koran as a nervous-looking groom awaits the arrival of his bride.

The young man bursts into a smile as his soon-to-be wife appears, clad in a brilliant white dress with matching headscarf.

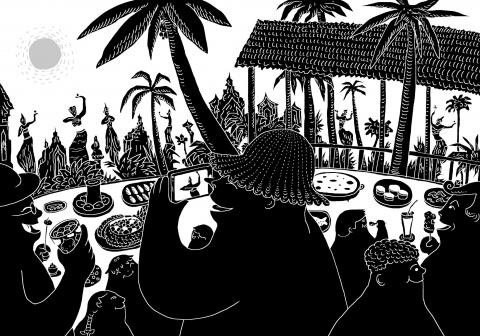

Illustration: Mountain People

The ceremony is one of dozens of marriages held over the past few months at Al Meroz — the city’s first entirely halal hotel.

Thailand has long been a draw for the world’s sunseekers and hedonists, drawn to its parties, red-light districts, cheap booze and tropical beaches.

However, it has also seen a huge influx of visitors from Muslim countries, part of a quiet, but deliberate strategy by the Southeast Asian nation to diversify its visitor profile.

“Considering there are 1.5 billion Muslims around the world, I think this is a very good market,” said Sanya Saenboon, the general manager of the hotel, one of a growing number of businesses serving a boom in Muslim tourists.

The hotel opened its doors last year, setting itself apart with its attention to all things Muslim.

For a start, there is no alcohol on sale, while the top floor swimming pool and gym have specific times for when men and women can use the facilities.

Everything in the building has been ticked off against a stringent checklist for practicing Muslims, from bed linen washed in a particular way to ensuring toiletries are free of alcohol or animal fat — making everyday goods “permissible” for the faithful.

Sanya, who is Muslim, said such checks give visitors “peace of mind” so clients never have to ask themselves: “Can I eat this?”

Despite a decade of political turbulence, Thailand has seen an explosion in tourist arrivals, from 13.8 million annual visitors in 2006 to a record 32.5 million last year.

Western arrivals have largely remained a constant. The biggest increase in arrivals comes from China, skyrocketing from just 949,000 arrivals 10 years ago to 8.7 million visitors last year.

However, Muslim countries are also sending their citizens.

An analysis of government figures shows visitors from key Muslim-majority nations in the Middle East and Asia rose from 2.63 million in 2006 to 6.03 million last year.

“Thailand was ahead of the curve,” said Fazal Baharden, founder of the Singapore-based Crescent Rating, which rates which countries are most welcoming to Muslim travelers.

Thailand routinely places in the top two for non-Muslim majority nations alongside Singapore in Crescent Ratings’ annual survey of halal destinations.

“They’ve really recognized the Muslim consumer market is worth tapping into,” he said, adding that medical tourism, shopping and high-quality hotels are the primary draws.

The Muslim travel market is one of the world’s fastest-growing, thanks to the growth of cheap flights and booming Muslim middle classes, Baharden said.

The number of Muslim travelers has surged from about 25 million per year in 2000 to 117 million in 2015, he estimated.

However, it is not just at home that Thailand has gone halal.

From chicken and seafood to rice and canned fruit, the country has long been one of the world’s great food exporters.

Now, a growing numbers of food companies are switching to halal to widen their customer base.

Against a backdrop of humming machines churning out butter, Lalana Thiranusornkij, a Buddhist, explains how her family turned their three factories — under the KCG Corp banner — halal to access markets in Indonesia, Malaysia and the Persian Gulf.

However, going halal sometimes required some clever work-arounds, such as how to avoid animal-based gelatin to make jelly.

“In the past we used gelatin from pork, but ... we changed our gelatin from the pork source to be from a seaweed source,” she said.

Thailand’s military junta has set the goal of turning the country into one of the world’s top five halal exporting nations by 2020.

Some outsiders might be surprised to see an overwhelmingly Buddhist nation embrace halal.

However, Winai Dahlan, founder of the Halal Science Center at Bangkok’s Chulalongkorn University, said Thailand was well placed to make the change.

Five percent of its population is Muslim and — outside of the insurgency-plagued southern border region — is well-integrated within the Buddhist majority.

It was local Thai Muslims who first began asking for the country’s halal testing center, a business that scours products for any banned substances and has since boomed.

“Fifteen years ago there was only 500 food plants that had halal certification. Now it’s 6,000,” Winai told reporters, as female lab technicians in headscarves tested food products for traces of pork DNA.

Over the same period, the number of halal-certified products made in Thailand has gone from 10,000 to 160,000, he said.

It has paid off. The government estimates the halal food industry is already worth US$6 billion per year.

As Thailand has quickly learned, there is gold at the end of the halal rainbow.

The conflict in the Middle East has been disrupting financial markets, raising concerns about rising inflationary pressures and global economic growth. One market that some investors are particularly worried about has not been heavily covered in the news: the private credit market. Even before the joint US-Israeli attacks on Iran on Feb. 28, global capital markets had faced growing structural pressure — the deteriorating funding conditions in the private credit market. The private credit market is where companies borrow funds directly from nonbank financial institutions such as asset management companies, insurance companies and private lending platforms. Its popularity has risen since

The Donald Trump administration’s approach to China broadly, and to cross-Strait relations in particular, remains a conundrum. The 2025 US National Security Strategy prioritized the defense of Taiwan in a way that surprised some observers of the Trump administration: “Deterring a conflict over Taiwan, ideally by preserving military overmatch, is a priority.” Two months later, Taiwan went entirely unmentioned in the US National Defense Strategy, as did military overmatch vis-a-vis China, giving renewed cause for concern. How to interpret these varying statements remains an open question. In both documents, the Indo-Pacific is listed as a second priority behind homeland defense and

Every analyst watching Iran’s succession crisis is asking who would replace supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Yet, the real question is whether China has learned enough from the Persian Gulf to survive a war over Taiwan. Beijing purchases roughly 90 percent of Iran’s exported crude — some 1.61 million barrels per day last year — and holds a US$400 billion, 25-year cooperation agreement binding it to Tehran’s stability. However, this is not simply the story of a patron protecting an investment. China has spent years engineering a sanctions-evasion architecture that was never really about Iran — it was about Taiwan. The

In an op-ed published in Foreign Affairs on Tuesday, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairwoman Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) said that Taiwan should not have to choose between aligning with Beijing or Washington, and advocated for cooperation with Beijing under the so-called “1992 consensus” as a form of “strategic ambiguity.” However, Cheng has either misunderstood the geopolitical reality and chosen appeasement, or is trying to fool an international audience with her doublespeak; nonetheless, it risks sending the wrong message to Taiwan’s democratic allies and partners. Cheng stressed that “Taiwan does not have to choose,” as while Beijing and Washington compete, Taiwan is strongest when