The puzzle is one of the greatest surrounding our species. On a planet that bristled with different types of human being, including Neanderthals and the Hobbit folk of Flores, only one is left today: Homo sapiens.

Our current solo status on Earth is therefore an evolutionary oddity — though it is not clear when our species became Earth’s only masters, nor is it clear why we survived when all other versions of humanity died out. Did we kill off our competitors, or were the others just poorly adapted and unable to react to the extreme climatic fluctuations that then beset the planet?

These key issues are to be tackled this week at a major conference at the British Museum in London, “When Europe was covered by ice and ash,” when scientists will reveal results from a five-year research program using modern dating techniques to answer these puzzles.

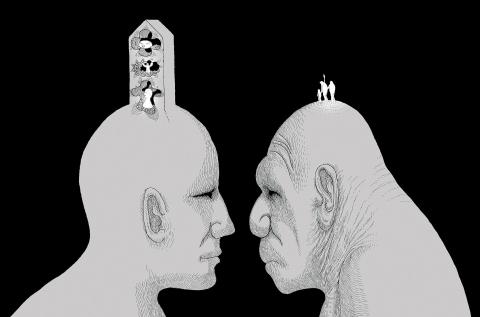

In particular, researchers have focused on the Neanderthals, a species very close in physique and brain size to modern humans. They once dominated Europe, but disappeared after modern humans arrived after emerging from our African homeland about 70,000 years ago. The question is: why?

“A major problem in understanding what happened when modern humans appeared in Europe has concerned the dates for our arrival,” Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London said. “It was once thought we appeared in Europe about 40,000 years ago and that we coexisted with Neanderthals for thousands of years after that. They may have hung on in pockets — including caves in Gibraltar — until 28,000 years ago, it was believed.”

In other words, there was a long, gradual takeover by modern humans — an idea that is likely to be demolished at this week’s conference, Stringer added.

Results from the five-year research program, RESET (Response of humans to abrupt environmental transitions), will show that humans arrived much earlier than previously estimated and that Neanderthals expired even more quickly. Careful dating of finds at sites across Europe suggests that Homo sapiens reached Europe 45,000 years ago. Five thousand years later, Neanderthals had disappeared. This latter finding is particularly striking.

“All previous research on Neanderthal sites, which have suggested that they were more recent than 40,000 years old — and there have been a lot of them — appear to be wrong,” Stringer added. “That is a key finding that will be discussed at the conference.”

Using radiocarbon technology to date remains that are 40,000 years old has always been tricky. Radioactive carbon decays relatively quickly and after 40,000 years there will only be a tiny amount left in a sample to measure. The tiniest piece of contaminant can then ruin dating efforts.

However, scientists working for the RESET program have set out to get round these problems. At Oxford University, scientists led by Tom Higham have developed new purification methods to prevent contamination and have been able to make much more precise radiocarbon dating for this period.

In addition, scientists have discovered that there was a devastating eruption of the Campi Flegrei volcano west of Naples 39,000 years ago. Recent studies have shown this eruption was much more destructive than previously recognized.

More than 250km3 of ash were blasted into the atmosphere and covered a vast area of eastern Europe and western Asia. This layer gives scientists a precise means of dating for this period and, combined with the new radiocarbon dating, shows there are no Neanderthal sites anywhere in Europe that are less than 39,000 years ago, a date 10,000 years older than previous estimates. It is a significant shift in our thinking about our nearest evolutionary cousins.

In addition, some researchers point out that Campi Flegrei was the biggest volcanic eruption in Europe for more than 200,000 years and would have had a catastrophic impact. Vast plumes of ash would have blotted out the sun for months, or possibly years, and caused temperatures to plummet. Sulphur dioxide, fluorine and chlorine emissions would have generated intense falls of acid rain. Neanderthals may simply have shivered and choked to death.

The Campi Flegrei eruption not only gives us a precise date for the Neanderthals’ disappearance, it may provide us with the cause of their extinction as well, though Stringer sounds a note of caution.

“Some researchers believe there is a link between the eruption and the Neanderthals’ disappearance, but I doubt it. From the new work carried out by RESET scientists, it looks as if the Neanderthals had already vanished. A few may still have been hanging around, of course, and Campi Flegrei may have delivered the coup de grace. But it would be wrong to think the eruption was the main cause of the Neanderthals’ demise,” he said.

In that case, what did do for the Neanderthals? Given the speed with which they disappeared from the face of the planet after modern humans arrived in Europe, it is probable that Homo sapiens played a critical role in their demise. That does not mean we chased them down and killed them — an unlikely scenario given their more muscular physiques. However, we may have been more successful at competing for resources, as several recent pieces of research have suggested.

Eiluned Pearce of Oxford University recently compared the skulls of 32 Homo sapiens and 13 Neanderthals and found that the latter had eye sockets that were significantly larger. These larger eyes were an adaptation to the long, dark nights of Europe, she concluded, and would have required much larger visual processing areas in the skulls of Neanderthals.

By contrast, modern humans, from sunny Africa, had no need for this adaptation and instead they evolved frontal lobes, which are associated with high-level processing.

“More of the Neanderthal brain appears to have been dedicated to vision and body control, leaving less brain to deal with other functions like social networking,” Pearce told BBC News.

This point is stressed by Stringer.

“Neanderthal brains were as big as modern humans’, but the former had bigger bodies — they were rounder and had more muscle. More of their brain cells would have been needed to control these larger bodies, on top of the added bits of cortex needed for their enhanced vision. That means they had less brain power available to them compared with modern humans,” he said.

Thus our ancestors possessed a fair bit of enhanced cerebral prowess, even though their brains were no bigger than Neanderthals’. How they used that extra brainpower is a little trickier to assess, though most scientists believe it maintained complex, extended social networks. Developing an ability to speak complex language would have been a direct outcome, for example.

Having extended networks of clans would have been a considerable advantage in Europe, which was then descending into another ice age. When times got hard for one group, help could be sought from another. Neanderthals would have less backup.

This point is supported by studies of the flints used for Neanderthal weapons. These are rarely found more than 48km from their source. By contrast, modern humans were setting up commercial operations that saw implements being transported more than 322km. Artefacts and figurines were being shared over wider and wider areas.

Cultural life become more increasingly important for humans. Research by Tanya Smith of Harvard University recently revealed that modern human childhoods became longer than those of Neanderthals. By studying the teeth of Neanderthal children, she found they grew much more quickly than modern human children. The growth of teeth is linked to overall development and shows Neanderthals must have had much shorter childhoods and a much reduced opportunity to learn from their parents and clan members.

“We moved from a primitive ‘live fast and die young’ strategy to a ‘live slow and grow old’ strategy and that has helped make humans one of the most successful organisms on the planet,” Smith said.

President William Lai (賴清德) attended a dinner held by the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) when representatives from the group visited Taiwan in October. In a speech at the event, Lai highlighted similarities in the geopolitical challenges faced by Israel and Taiwan, saying that the two countries “stand on the front line against authoritarianism.” Lai noted how Taiwan had “immediately condemned” the Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel by Hamas and had provided humanitarian aid. Lai was heavily criticized from some quarters for standing with AIPAC and Israel. On Nov. 4, the Taipei Times published an opinion article (“Speak out on the

More than a week after Hondurans voted, the country still does not know who will be its next president. The Honduran National Electoral Council has not declared a winner, and the transmission of results has experienced repeated malfunctions that interrupted updates for almost 24 hours at times. The delay has become the second-longest post-electoral silence since the election of former Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernandez of the National Party in 2017, which was tainted by accusations of fraud. Once again, this has raised concerns among observers, civil society groups and the international community. The preliminary results remain close, but both

News about expanding security cooperation between Israel and Taiwan, including the visits of Deputy Minister of National Defense Po Horng-huei (柏鴻輝) in September and Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) this month, as well as growing ties in areas such as missile defense and cybersecurity, should not be viewed as isolated events. The emphasis on missile defense, including Taiwan’s newly introduced T-Dome project, is simply the most visible sign of a deeper trend that has been taking shape quietly over the past two to three years. Taipei is seeking to expand security and defense cooperation with Israel, something officials

Eighty-seven percent of Taiwan’s energy supply this year came from burning fossil fuels, with more than 47 percent of that from gas-fired power generation. The figures attracted international attention since they were in October published in a Reuters report, which highlighted the fragility and structural challenges of Taiwan’s energy sector, accumulated through long-standing policy choices. The nation’s overreliance on natural gas is proving unstable and inadequate. The rising use of natural gas does not project an image of a Taiwan committed to a green energy transition; rather, it seems that Taiwan is attempting to patch up structural gaps in lieu of