Like every Chinese child, Li Hanwei spent her schooldays memorizing thousands of the intricate characters that make up the Chinese writing system.

Yet aged just 21 and now a university student in Hong Kong, Li already finds that when she picks up a pen to write, the characters for words as simple as “embarrassed” have slipped from her mind.

“I can remember the shape, but I can’t remember the strokes that you need to write it,” she said. “It’s a bit of a problem.”

Surveys indicate the phenomenon, dubbed “character amnesia,” is widespread across China, causing young Chinese to fear for the future of their ancient writing system.

Young Japanese people also report the problem, which is caused by the constant use of computers and mobile phones with alphabet-based input systems.

There is even a Chinese word for it: tibiwangzi (提筆忘字) or “take pen, forget character.”

A poll commissioned by the China Youth Daily in April found that 83 percent of the 2,072 respondents admitted having problems writing characters.

As a result, Li says she has become almost dependent on her telephone.

“When I can’t remember, I will take out my cellphone and find it [the character] and then copy it down,” she said.

“I think it’s a young people’s problem, or at least a computer users’ problem,” said Zeng Ming, 22, from Guangdong Province.

One notoriously forgettable character, Zeng says, is used in the word Tao Tie — a legendary Chinese monster that was so greedy it ate itself.

Still used as a byword for gluttony, the Tao Tie is one of many ancient Chinese concepts embedded in the language.

“It’s like you’re forgetting your culture,” Zeng says.

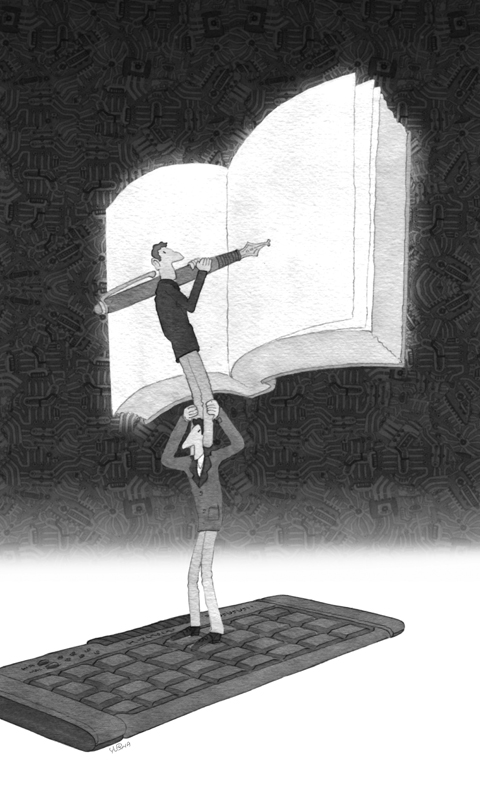

Character amnesia happens because most Chinese use electronic input systems based on pinyin, which translates Chinese characters into the Roman alphabet.

The user enters each word using pinyin, and the device offers a menu of characters that match. So users must recognize the character, but they don’t need to be able to write it. In Japan, where three writing systems are combined into one, mobiles and computers use the simpler hiragana and katakana scripts for inputting — meaning users may forget the kanji, a third strand of Japanese writing similar to Chinese characters.

“We rely too much on the conversion function on our phones and PCs,” said Ayumi Kawamoto, 23, shopping in Tokyo’s upscale Ginza district. “I’ve mostly forgotten characters I learned in middle and high school and I tend to forget the characters I only occasionally use.”

“I hardly hand-write anymore, which is the main reason why I have forgotten so many characters,” said Maya Kato, a 22-year-old Tokyo student.

“It is frustrating because I always almost remember the character, and lose it at the last minute. I forget if there was an extra line, or where the dot is supposed to go,” she said.

Character amnesia matters because memorization is so crucial to character-based written languages, says Siok Wai Ting, assistant professor of linguistics at Hong Kong University. Forgetting how to write could eventually affect reading ability.

“There is no way we can learn the writing systematically because the writing itself is not systematic — we have to memorize, we have to rote learn,” she said. “Through writing, we memorize the characters. Reading and writing are more closely connected in Chinese.”

Chinese reading even uses a different part of the brain from reading the Roman alphabet, Siok’s research has found — a part closer to the motor area, which is used for handwriting.

Chinese characters are so complex that the country’s revolutionary leader Mao Zedong (毛澤東) told the US journalist Edgar Snow in 1936: “Sooner or later, we believe, we will have to abandon characters altogether if we are to create a new social culture in which the masses fully participate.”

Instead, Mao eventually chose to simplify many characters into forms that are now the standard in mainland China.

Victor Mair, professor of Chinese language and literature at the University of Pennsylvania, said character amnesia is part of a “natural process of evolution.”

“The reasons why characters are innately difficult to enter into computers and mobile phones are innate to the character-based writing systems themselves,” he said.

“There are no magic bullets that will make it easy to input characters,” he said.

The Wubi input system — available on some Chinese computers and backed by the government — uses character strokes as handwriting does. But the system itself is so difficult to learn that it has failed to gain mass appeal.

However, iPhones and other smartphones now offer an option in which users can input characters by drawing them onto the touch screen.

And in Japan, kanji kentei — a character quiz with 12 levels — has become a widespread craze among schoolchildren, housewives and retirees, said Yoshiko Nakano, associate professor of Japanese at the University of Hong Kong.

Some argue that the perceived decline in character knowledge is, in fact, nothing to worry about.

A survey by the southern Chinese news portal Dayang Net, found that 80 percent of respondents had forgotten how to write some characters, but 43 percent said they used handwritten characters only for signatures and forms.

“The idea that China is a country full of people who write beautiful, fluid literature in characters without a second thought is a romantic fantasy,” blogger and translator C. Custer wrote on his Chinageeks blog. “Given the social and financial pressures that exist for most people in China ... [and] given that nearly everyone has a cellphone, it really isn’t a problem at all.”

The explosion of Internet and phone technology has itself led to the creation of new words and forms of writing. In 2008 Chinese were sending 175 billion text messages each quarter, Xinhua news agency said.

Still, both Li and Zeng have become so concerned about character amnesia that they keep handwritten diaries partly to ensure they don’t forget how to write.

If it weren’t for this, would they actually need to remember how to write characters with a pen?

Li is almost stumped, but says she uses one “when I have to sign the back of my new credit card.”

“That’s almost all,” she said.

Jan. 1 marks a decade since China repealed its one-child policy. Just 10 days before, Peng Peiyun (彭珮雲), who long oversaw the often-brutal enforcement of China’s family-planning rules, died at the age of 96, having never been held accountable for her actions. Obituaries praised Peng for being “reform-minded,” even though, in practice, she only perpetuated an utterly inhumane policy, whose consequences have barely begun to materialize. It was Vice Premier Chen Muhua (陳慕華) who first proposed the one-child policy in 1979, with the endorsement of China’s then-top leaders, Chen Yun (陳雲) and Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平), as a means of avoiding the

The last foreign delegation Nicolas Maduro met before he went to bed Friday night (January 2) was led by China’s top Latin America diplomat. “I had a pleasant meeting with Qiu Xiaoqi (邱小琪), Special Envoy of President Xi Jinping (習近平),” Venezuela’s soon-to-be ex-president tweeted on Telegram, “and we reaffirmed our commitment to the strategic relationship that is progressing and strengthening in various areas for building a multipolar world of development and peace.” Judging by how minutely the Central Intelligence Agency was monitoring Maduro’s every move on Friday, President Trump himself was certainly aware of Maduro’s felicitations to his Chinese guest. Just

A recent piece of international news has drawn surprisingly little attention, yet it deserves far closer scrutiny. German industrial heavyweight Siemens Mobility has reportedly outmaneuvered long-entrenched Chinese competitors in Southeast Asian infrastructure to secure a strategic partnership with Vietnam’s largest private conglomerate, Vingroup. The agreement positions Siemens to participate in the construction of a high-speed rail link between Hanoi and Ha Long Bay. German media were blunt in their assessment: This was not merely a commercial win, but has symbolic significance in “reshaping geopolitical influence.” At first glance, this might look like a routine outcome of corporate bidding. However, placed in

China often describes itself as the natural leader of the global south: a power that respects sovereignty, rejects coercion and offers developing countries an alternative to Western pressure. For years, Venezuela was held up — implicitly and sometimes explicitly — as proof that this model worked. Today, Venezuela is exposing the limits of that claim. Beijing’s response to the latest crisis in Venezuela has been striking not only for its content, but for its tone. Chinese officials have abandoned their usual restrained diplomatic phrasing and adopted language that is unusually direct by Beijing’s standards. The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs described the