Every 50 years or so, US magazine The Atlantic lobs an intellectual grenade into our culture. In the summer of 1945, for example, it published an essay by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) engineer Vannevar Bush entitled “As We May Think.” It turned out to be the blueprint for what eventually emerged as the World Wide Web. Two summers ago, The Atlantic published an essay by Nicholas Carr, one of the blogosphere’s most prominent (and thoughtful) contrarians, under the headline “Is Google Making Us Stupid?”

“Over the past few years,” Carr wrote, “I’ve had an uncomfortable sense that someone, or something, has been tinkering with my brain, remapping the neural circuitry, reprogramming the memory. My mind isn’t going — so far as I can tell — but it’s changing. I’m not thinking the way I used to think. I can feel it most strongly when I’m reading. Immersing myself in a book or a lengthy article used to be easy. My mind would get caught up in the narrative or the turns of the argument and I’d spend hours strolling through long stretches of prose. That’s rarely the case anymore. Now, my concentration often starts to drift after two or three pages. I get fidgety, lose the thread, begin looking for something else to do. I feel as if I’m always dragging my wayward brain back to the text. The deep reading that used to come naturally has become a struggle.”

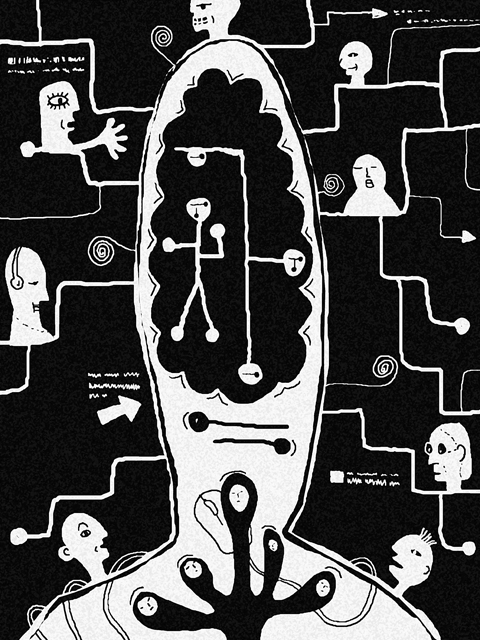

The title of the essay was misleading, because Carr’s target was not really the world’s leading search engine, but the impact that ubiquitous, always-on networking is having on our cognitive processes. His argument was that our deepening dependence on networking technology is indeed changing not only the way we think, but also the structure of our brains.

Carr’s article touched a nerve and has provoked a lively, ongoing debate on the Internet and in print (he has now expanded it into a book, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains).

This is partly because he’s an engaging writer who has vividly articulated the unease that many adults feel about the way their modi operandi have changed in response to ubiquitous networking. Who bothers to write down or memorize detailed information any more, for example, when they know that Google will always retrieve it if it’s needed again?

The Web has become, in a way, a global prosthesis for our collective memory.

It’s easy to dismiss Carr’s concern as just the latest episode of the moral panic that always accompanies the arrival of a new communications technology. People fretted about printing, photography, the telephone and television in analogous ways. It even bothered Plato, who argued that the technology of writing would destroy the art of remembering.

However, just because fears recur doesn’t mean that they aren’t valid. There’s no doubt that communications technologies shape and reshape society — just look at the impact that printing and the broadcast media have had on our world. The question that we couldn’t answer before now was whether these technologies could also reshape us.

Carr argues that modern neuroscience, which has revealed the “plasticity” of the human brain, shows that our habitual practices can actually change our neuronal structures. The brains of illiterate people, for example, are structurally different from those of people who can read. So if the technology of printing — and its concomitant requirement to learn to read — could shape human brains, then surely it’s logical to assume that our addiction to networking technology will do something similar?

Not all neuroscientists agree with Carr and some psychologists are skeptical. Harvard’s Steven Pinker, for example, is openly dismissive. However, many commentators who accept the thrust of his argument seem not only untroubled by its far-reaching implications, but are positively enthusiastic about them.

When the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life project asked its panel of more than 370 Internet experts for their reaction, 81 percent of them agreed with the proposition that “people’s use of the Internet has enhanced human intelligence.”

Others argue that the increasing complexity of our environment means that we need the Internet as “power steering for the mind.” We may be losing some of the capacity for contemplative concentration that was fostered by a print culture, they say, but we’re gaining new and essential ways of working.

“The trouble isn’t that we have too much information at our fingertips,” the futurologist Jamais Cascio says, “but that our tools for managing it are still in their infancy. Worries about ‘information overload’ predate the rise of the Web ... and many of the technologies that Carr worries about were developed precisely to help us get some control over a flood of data and ideas. Google isn’t the problem — it’s the beginning of a solution.”

The US Senate’s passage of the 2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which urges Taiwan’s inclusion in the Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise and allocates US$1 billion in military aid, marks yet another milestone in Washington’s growing support for Taipei. On paper, it reflects the steadiness of US commitment, but beneath this show of solidarity lies contradiction. While the US Congress builds a stable, bipartisan architecture of deterrence, US President Donald Trump repeatedly undercuts it through erratic decisions and transactional diplomacy. This dissonance not only weakens the US’ credibility abroad — it also fractures public trust within Taiwan. For decades,

In 1976, the Gang of Four was ousted. The Gang of Four was a leftist political group comprising Chinese Communist Party (CCP) members: Jiang Qing (江青), its leading figure and Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) last wife; Zhang Chunqiao (張春橋); Yao Wenyuan (姚文元); and Wang Hongwen (王洪文). The four wielded supreme power during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), but when Mao died, they were overthrown and charged with crimes against China in what was in essence a political coup of the right against the left. The same type of thing might be happening again as the CCP has expelled nine top generals. Rather than a

Taiwan Retrocession Day is observed on Oct. 25 every year. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) government removed it from the list of annual holidays immediately following the first successful transition of power in 2000, but the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT)-led opposition reinstated it this year. For ideological reasons, it has been something of a political football in the democratic era. This year, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) designated yesterday as “Commemoration Day of Taiwan’s Restoration,” turning the event into a conceptual staging post for its “restoration” to the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The Mainland Affairs Council on Friday criticized

A Reuters report published this week highlighted the struggles of migrant mothers in Taiwan through the story of Marian Duhapa, a Filipina forced to leave her infant behind to work in Taiwan and support her family. After becoming pregnant in Taiwan last year, Duhapa lost her job and lived in a shelter before giving birth and taking her daughter back to the Philippines. She then returned to Taiwan for a second time on her own to find work. Duhapa’s sacrifice is one of countless examples among the hundreds of thousands of migrant workers who sustain many of Taiwan’s households and factories,