To paraphrase former British prime minister Winston Churchill, never have so many billions of dollars been pumped out by so many governments and central banks. The US government is pumping US$789 billion into its economy, Europe US$255 billion and China US$587 billion. The US Federal Reserve increased its stock of base money last year by 97 percent, the European Central Bank (ECB) by 37 percent. The Federal funds rate in the US is practically zero, and the ECB’s main refinancing rate, already at an all-time low of 2 percent, will likely fall further in the coming months.

The Fed has given ordinary banks direct access to its credit facilities, and the ECB no longer rations the supply of base money, instead providing as much liquidity as banks demand. Since last October, Western countries’ rescue packages for banks have reached about US$4.3 trillion.

Many now fear that these huge infusions of cash will make inflation inevitable. In Germany, which suffered from hyper-inflation in 1923, there is widespread fear that people will again lose their savings and need to start from scratch. Other countries share this concern, if to a lesser extent.

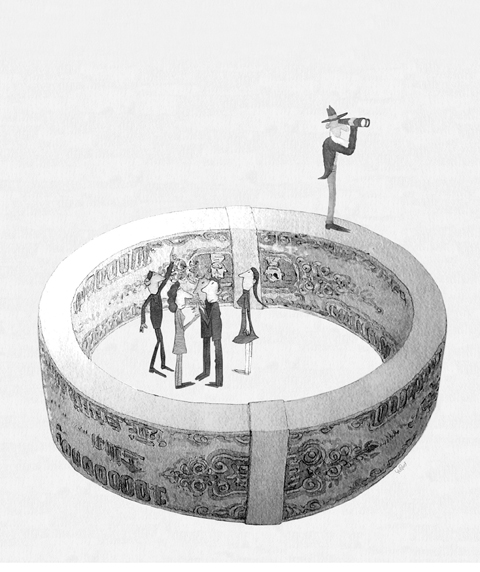

But these fears are not well founded. True, the stock of liquidity is rising rapidly. But it is rising because the private sector is hoarding money rather than spending it. By providing extra liquidity, central banks merely reduce the amount of money withdrawn from expenditure on goods and services, which mitigates, but does not reverse, the negative demand shock that hit the world economy.

This is a trivial but important point that follows from the theory of supply and demand. Think of the oil market, for example. It is impossible to infer solely from an increase in the volume of transactions how the price of oil will change. The price will fall if the increase resulted from growth in supply, and it will rise if the increase resulted from growth in demand.

With the increase in the aggregate stock of money balances, things are basically the same. If this increase resulted from an increase in supply, the value of money will go down, which means inflation. But if it resulted from an increase in demand, the value of money will increase, which means deflation. Obviously, the latter risk is more relevant in today’s conditions.

If the underlying price trend is added to this, it is easily understandable why inflation rates are currently coming down everywhere. In the US, the annual inflation rate fell from 5.6 percent last July to 0.1 percent in December, and in Europe from 4.4 percent last July to 2.2 percent in January.

At the moment, no country is truly suffering deflation, but that may change as the crisis deepens. Germany, with its notoriously low inflation rate, may be among the first countries to experience declining prices. The most recent data show that the price index in January was up by only 0.9 percent year on year.

This deflationary tendency will create serious economic problems, which do not necessarily result from deflation as such, but may stem from a natural resistance to deflation. In each country, a number of prices are rigid, because sellers resist selling cheaper, as low productivity gains and wage defense by unions leave no margin for lower prices. Thus, deflationary pressure will to some extent result in downward quantity adjustments, which will deepen the real crisis.

Moreover, even if prices on average exhibit some downward flexibility, deflation necessarily increases the real rate of interest, given that nominal interest rates cannot fall below zero. The result is an increase in the cost of capital to firms, which lowers investment and exacerbates the crisis. This would be a particular problem for the US, where the Fed allowed the Federal funds rate to approach zero in January.

The only plausible inflationary scenario presupposes that when economies recover, central banks do not raise interest rates sufficiently in the coming boom, keeping too much of the current liquidity in the market.

Such a scenario is not impossible. This is the policy Italians pursued for decades in the pre-euro days, and the Fed might one day feel that it should adopt such a stance.

But the ECB, whose only mandate is to maintain price stability, cannot pursue this policy without fundamental changes in legislation. Moreover, this scenario cannot take place before the slump has turned into a boom. So, for the time being, the risk of inflation simply does not exist.

Japan provides good lessons about where the true risks are, as it has been suffering from deflation or near-deflation for 14 years. Since 1991, Japan has been mired in what Harvard economist Alvin Hansen, a contemporary of Keynes, once described as “secular stagnation.”

Ever since Japan’s banking crisis began in 1990, the country has been in a liquidity trap, with central bank rates close to zero, and from 1998 to 2005 the price level declined by more than 4 percent. Japanese governments have tried to overcome the slump with Hansen’s recipes, issuing one Keynesian program of deficit spending after the other and pushing the debt-to-GDP ratio from 64 percent in 1991 to 171 percent last year.

But all of that helped only a little. Japan is still stagnating. Not inflation, but a Japanese-type period of deflationary pressure with ever increasing public debt is the real risk that the world will be facing for years to come.

Hans-Werner Sinn is a professor of economics and finance at the University of Munich and president of the Ifo Institute.

COPYRIGHT: PROJECT SYNDICATE

The conflict in the Middle East has been disrupting financial markets, raising concerns about rising inflationary pressures and global economic growth. One market that some investors are particularly worried about has not been heavily covered in the news: the private credit market. Even before the joint US-Israeli attacks on Iran on Feb. 28, global capital markets had faced growing structural pressure — the deteriorating funding conditions in the private credit market. The private credit market is where companies borrow funds directly from nonbank financial institutions such as asset management companies, insurance companies and private lending platforms. Its popularity has risen since

The Donald Trump administration’s approach to China broadly, and to cross-Strait relations in particular, remains a conundrum. The 2025 US National Security Strategy prioritized the defense of Taiwan in a way that surprised some observers of the Trump administration: “Deterring a conflict over Taiwan, ideally by preserving military overmatch, is a priority.” Two months later, Taiwan went entirely unmentioned in the US National Defense Strategy, as did military overmatch vis-a-vis China, giving renewed cause for concern. How to interpret these varying statements remains an open question. In both documents, the Indo-Pacific is listed as a second priority behind homeland defense and

Every analyst watching Iran’s succession crisis is asking who would replace supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Yet, the real question is whether China has learned enough from the Persian Gulf to survive a war over Taiwan. Beijing purchases roughly 90 percent of Iran’s exported crude — some 1.61 million barrels per day last year — and holds a US$400 billion, 25-year cooperation agreement binding it to Tehran’s stability. However, this is not simply the story of a patron protecting an investment. China has spent years engineering a sanctions-evasion architecture that was never really about Iran — it was about Taiwan. The

In an op-ed published in Foreign Affairs on Tuesday, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairwoman Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) said that Taiwan should not have to choose between aligning with Beijing or Washington, and advocated for cooperation with Beijing under the so-called “1992 consensus” as a form of “strategic ambiguity.” However, Cheng has either misunderstood the geopolitical reality and chosen appeasement, or is trying to fool an international audience with her doublespeak; nonetheless, it risks sending the wrong message to Taiwan’s democratic allies and partners. Cheng stressed that “Taiwan does not have to choose,” as while Beijing and Washington compete, Taiwan is strongest when