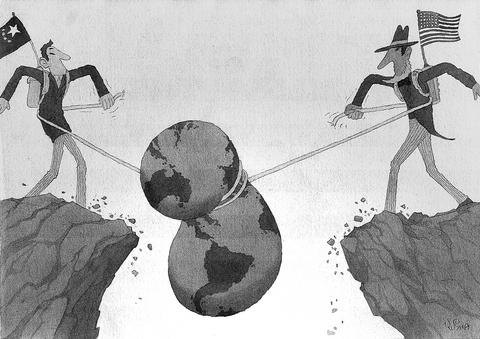

At the time of Sept. 11 and the invasion of Iraq, the US stood supreme with barely a challenge visible on any meaningful time horizon.

Almost five years on, we can clearly see both the inadequacies in the then-prevailing common sense, and the fallacies intrinsic to the neoconservative view of the world. There are, of course, always limits to power, even if they are not visible. The last five years have made the limits of US power plainly visible.

It is Iraq that has exposed those limits. The idea of US omnipotence always depended on its overwhelming military power, and the neoconservatives saw the latter as the key to a new era of US ascendancy. Iraq has demonstrated the limits of military power when it comes to subduing and governing a society. This failure has curbed the desire to intervene elsewhere: even if military action is contemplated in Iran, which now seems less likely, there will be no Iraq-style invasion and occupation.

The idea that Iraq would be a precursor to a new kind of US empire -- as advocated by Niall Ferguson, for example, in his book The Colossus -- is dead is subject to other limitations. What underpins power -- all kinds of power -- is economic strength, and in this respect the US is the subject of both a short-term crisis -- the twin deficits -- and a longer-term constraint, namely the fact that it accounts for a declining share of global GDP.

Iraq also demonstrated another profound shortcoming in the neo-conservative worldview. It was seen as both important in its own right, and as a means of reorganizing the Middle East. But this approach, magnified by the failure to subdue Iraq, led to an overwhelming preoccupation with the Middle East and, to a much lesser extent, central Asia, and the implicit relegation and neglect of US interests elsewhere. Perhaps superpowers always overreach themselves; arguably it is an occupational hazard. But history will surely judge the invasion of Iraq to have been a huge miscalculation and the moment when the geopolitical decline of the US, following the end of the Cold War, first became manifest.

In contrast to five years ago, the likely identity of the next superpower has become crystal clear. It is no longer just a possibility that it will be China; on the contrary, the probability is extremely high, if not yet a racing certainty. Nor does the timescale of this change have us peering into the distant future as it did five years ago. China is already beginning to acquire some of the interests and motivations of a superpower, and even a little of the demeanor. China feels like a parallel universe to the US, and certainly Europe. There is an expansive mood about the place. China is growing in self-confidence by the day.

And with good reason. There is no sign of China's economic growth abating, and it is this that lies behind its growing confidence. The massive contrasts between China and the US, both socially and economically, are enjoined in the argument over the US' trade deficit with China. The latter is deeply aware that its future prospects depend on the continuation of its economic growth and this remains its priority. But no longer to the exclusion of all else: China is beginning to widen its range of concerns and interests.

This has received most airplay in the context of China's search for secure supplies of oil and other commodities. To this end it has been acquiring a growing diplomatic presence in regions of the world like Africa and Latin America, making the US increasingly nervous about China's intentions.

This is understandable. China's growing economic clout and connections mean that it will increasingly offer an alternative to the US as an economic partner, and China is making it perfectly plain that it will not insist on the same kind of political strings as the US. We are only at the beginning of what will over time become a growing competition for the hearts and minds of the developing world.

In his speech at Yale University during his recent visit to the US, President Hu Jintao (胡錦濤) set out -- for the first time in such a forum -- the Chinese view of a harmonious world based on the idea of Chinese civilization. The most dramatic changes, though -- albeit sotto voce -- have been taking place in east Asia.

Though far from Europe's line of vision -- it has had little stake in the region since the postwar collapse of the European empires there -- east Asia is pivotal to China's prospects and the future of Sino-US relations. For the last decade, China has been busy overhauling its approach to the region and involving itself for the first time in its multilateral arrangements. This process has been steadily accelerating, especially since the Asian financial crisis.

The key has been China's developing relationship with ASEAN, which comprises the nations of Southeast Asia and is by far the most important regional institution. China has made the running -- ahead of Japan -- in the creation of a nascent broader regional framework.

In Northeast Asia, it has used its role in the talks over North Korea to forge a much closer relationship with South Korea. All very reasonable. The result, however, has been the slow but steady marginalization of the US, a process exacerbated by the fact that US attention has been overwhelmingly directed towards the Middle East, which in the long run is actually far less important.

It is a combination of these developments that perhaps helps to explain why Hu Jintao's visit to the US was not accorded the full status of a visiting head of state. It was a deliberate snub, reflecting the unease with which Washington views the rise of China and its possible implications. But this was more a matter of pique than substance.

It is now too late for the administration of US President George W. Bush to seriously rethink its relationship with China, but this will surely be top of the agenda for the next administration. But it admits no easy solution. Whatever the Pentagon may suggest, the Chinese have been careful to avoid posing a military challenge to the US, which lay at the heart of the Cold War antagonism between the US and the Soviet Union.

Moreover, again unlike in the Cold War, the two countries now find themselves highly economically interdependent. Yet China's continuing rise is bound to provoke growing disquiet and anxiety in Washington. It is this relationship that will lie at the center of global politics; if that is not apparent at the moment, it will be very soon.

Martin Jacques is a visiting professor at Renmin University.

China’s recent aggressive military posture around Taiwan simply reflects the truth that China is a millennium behind, as Kobe City Councilor Norihiro Uehata has commented. While democratic countries work for peace, prosperity and progress, authoritarian countries such as Russia and China only care about territorial expansion, superpower status and world dominance, while their people suffer. Two millennia ago, the ancient Chinese philosopher Mencius (孟子) would have advised Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) that “people are the most important, state is lesser, and the ruler is the least important.” In fact, the reverse order is causing the great depression in China right now,

We are used to hearing that whenever something happens, it means Taiwan is about to fall to China. Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) cannot change the color of his socks without China experts claiming it means an invasion is imminent. So, it is no surprise that what happened in Venezuela over the weekend triggered the knee-jerk reaction of saying that Taiwan is next. That is not an opinion on whether US President Donald Trump was right to remove Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro the way he did or if it is good for Venezuela and the world. There are other, more qualified

This should be the year in which the democracies, especially those in East Asia, lose their fear of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) “one China principle” plus its nuclear “Cognitive Warfare” coercion strategies, all designed to achieve hegemony without fighting. For 2025, stoking regional and global fear was a major goal for the CCP and its People’s Liberation Army (PLA), following on Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) Little Red Book admonition, “We must be ruthless to our enemies; we must overpower and annihilate them.” But on Dec. 17, 2025, the Trump Administration demonstrated direct defiance of CCP terror with its record US$11.1 billion arms

The immediate response in Taiwan to the extraction of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro by the US over the weekend was to say that it was an example of violence by a major power against a smaller nation and that, as such, it gave Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) carte blanche to invade Taiwan. That assessment is vastly oversimplistic and, on more sober reflection, likely incorrect. Generally speaking, there are three basic interpretations from commentators in Taiwan. The first is that the US is no longer interested in what is happening beyond its own backyard, and no longer preoccupied with regions in other