At the foot of the majestic Carpathian mountains, Petrila waits in dread for the closure of its coal mine, the oldest in Romania and the life force of a town struggling to survive.

“We are already the valley of tears; we don’t want to become the valley of death,” one resident said, referring to the Jiu Valley where Petrila lies, Romania’s main coal mining region where miners’ numbers have dwindled to only a fraction of those employed in the 1990s.

Petrila’s 153-year-old mine has not only been the town’s livelihood, but its very identity. Petrila without mines would be like Bordeaux without its vineyards or Silicon Valley without its IT firms, locals say.

Photo: AFP

However, pressure from the European Commission, the EU executive, on member governments to cut subsidies to lossmaking mines means the one in Petrila, two elsewhere in Romania and several others across the 27-member bloc will be shut down by 2018. Demolition work has already started.

“It’s the age-old story of the deindustrialization of Europe,” said David Schwartz, a Bucharest director who recently drew attention for Underground, a play he and the well-known Romanian playwright Mihaela Michailov worked on for a year, giving voice to the miners and their families in this once-prosperous company town.

The EU’s plan is to shift subsidies from mines toward renewable energies. Up to 30,000 jobs, out of a total 100,000 in the EU mining sector, could be lost.

Photo: AFP

In Spain, angry miners have staged protests and clashed with police, but those in Romania appear resigned to their fate, still smarting from violent protests in 1990 that many feel stigmatized them wrongly.

That year, then-Romanian president Ion Iliescu called about 10,000 Jiu Valley miners to Bucharest to end protests against his government, the first elected after the fall of the communist regime, but one made up mostly of former communists, like himself.

The miners were severely criticized for using force against protesters, but many today say those who took part were “manipulated.”

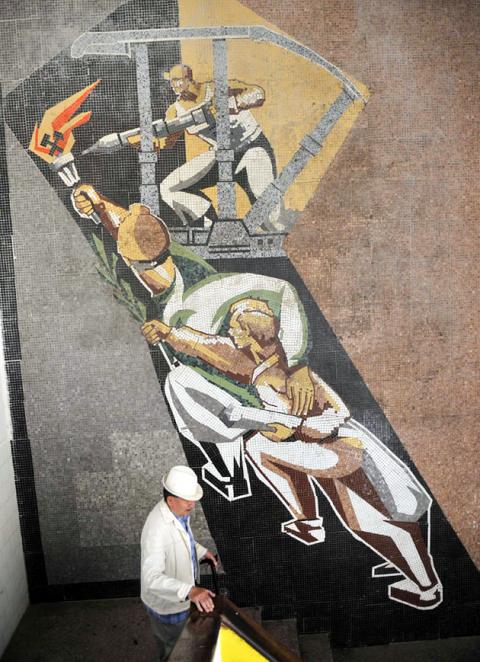

Communist-era mosaics at the Petrila mine are a reminder of its flourishing past before the economic decline of the last two decades.

In 1988, the town had about 4,000 miners, now there are 688. In the wider Jiu Valley, numbers have dropped from 50,000 to 7,600, Petrila mine director Constantin Jujan said.

“In 1997, a wave of redundancies at the time meant people suddenly got a lot of money. But they weren’t ready; they spent, they set up businesses and got in debt, found themselves without homes, with nothing,” said local restaurant owner Elena Chelba, whose husband and father are both miners.

Today the unemployment rate in the town is more than 40 percent.

Charity shops proposing second-hand clothes, crockery and toys are testimony to the hard times.

“I don’t know if things can get any worse,” Chelba said. “But if the mine closes, things will not be rosy; so many people depend on it.”

Everyday, ignoring the danger, dozens of locals jump on the trains bringing coal to Petrila to steal a few lumps, either to keep warm or to sell.

One of them, who gave only his first name, Traian, collects what coal he finds on the tracks in red buckets — there is no way his pension of 200 euros (US$244) a month can pay for heating.

Traian’s son has left Romania for Germany, and his daughter will join him for two months of seasonal work. Like many, Traian doesn’t complain for himself, but worries about his children. Emigration is often seen as the only answer.

“My daughter’s future is not here,” one miner said solemnly, tramping out of the mine after a night’s work.

“Some families cannot pay their gas and electricity bills any more. We give them clothes so their children are not ashamed to go to school,” said Florin Popescu, who runs the local branch of Save the Children.

The center ensures that about 100 children get a hot meal, as well as psychological and educational help.

“We know that we will have to leave because there is no work here. It’s sad for me because this is where I have grown up and where my friends are,” said Cristinel Homoc, a 15-year-old who dreams of becoming a soccer player or a lawyer.

Some residents hope for better days in a region that they believe has immense tourism potential.

Stretching about 1,500km across central Europe, the Carpathians are blessed with virgin forest, rich flora and wildlife, including lynx and bears.

Romanian culture is also a draw. A local caricaturist, Ion Barbu, organizes festivals and has turned the childhood home of writer Ion D. Sirbu — a key opposition figure during Nicolae Ceausescu’s dictatorship — into a museum.

Barbu, like many other residents, wants to preserve the buildings at the mine site to create cultural and “industrial” tourism, to retain Petrila’s link with its prouder past.

Industrial tourism has worked in other areas: UNESCO designated three former mining sites in the Wallonia region of southern Belgium and one site in northern France as World Heritage sites.

However, the residents’ dreams have met with opposition from Petrila deputy mayor Constantin Ramascanu, who would prefer to raze the site.

Rejecting all ideas of green tourism — even from Britain’s Prince Charles, who has tried to develop rural tourism in Romania — Ramascanu’s vision is a valley covered in hotels, casinos and quad-biking tracks.

KEEPING UP: The acquisition of a cleanroom in Taiwan would enable Micron to increase production in a market where demand continues to outpace supply, a Micron official said Micron Technology Inc has signed a letter of intent to buy a fabrication site in Taiwan from Powerchip Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp (力積電) for US$1.8 billion to expand its production of memory chips. Micron would take control of the P5 site in Miaoli County’s Tongluo Township (銅鑼) and plans to ramp up DRAM production in phases after the transaction closes in the second quarter, the company said in a statement on Saturday. The acquisition includes an existing 12 inch fab cleanroom of 27,871m2 and would further position Micron to address growing global demand for memory solutions, the company said. Micron expects the transaction to

Vincent Wei led fellow Singaporean farmers around an empty Malaysian plot, laying out plans for a greenhouse and rows of leafy vegetables. What he pitched was not just space for crops, but a lifeline for growers struggling to make ends meet in a city-state with high prices and little vacant land. The future agriculture hub is part of a joint special economic zone launched last year by the two neighbors, expected to cost US$123 million and produce 10,000 tonnes of fresh produce annually. It is attracting Singaporean farmers with promises of cheaper land, labor and energy just over the border.

US actor Matthew McConaughey has filed recordings of his image and voice with US patent authorities to protect them from unauthorized usage by artificial intelligence (AI) platforms, a representative said earlier this week. Several video clips and audio recordings were registered by the commercial arm of the Just Keep Livin’ Foundation, a non-profit created by the Oscar-winning actor and his wife, Camila, according to the US Patent and Trademark Office database. Many artists are increasingly concerned about the uncontrolled use of their image via generative AI since the rollout of ChatGPT and other AI-powered tools. Several US states have adopted

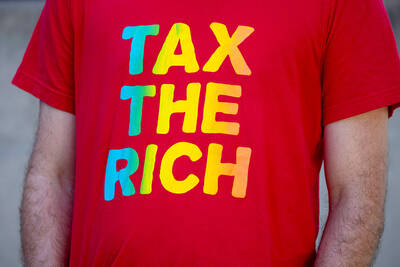

A proposed billionaires’ tax in California has ignited a political uproar in Silicon Valley, with tech titans threatening to leave the state while California Governor Gavin Newsom of the Democratic Party maneuvers to defeat a levy that he fears would lead to an exodus of wealth. A technology mecca, California has more billionaires than any other US state — a few hundred, by some estimates. About half its personal income tax revenue, a financial backbone in the nearly US$350 billion budget, comes from the top 1 percent of earners. A large healthcare union is attempting to place a proposal before