A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest.

But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is the longest-running project of its kind in the world, and has become a source for dozens of academic articles in fields ranging from meteorology to ecology and physiology.

Understanding how drought can affect the Amazon, an area twice the size of India that crosses into several South American nations, has implications far beyond the region. The rainforest stores a massive amount of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that is the main driver of climate change. According to one study, the Amazon stores the equivalent of two years of global carbon emissions, which mainly come from the burning of coal, oil and gasoline. When trees are cut, or wither and die from drought, they release into the atmosphere the carbon they were storing, which accelerates global warming.

Photo: AP

OBSERVING RESULTS

To mimic stress from drought, the project, located in the Caxiuana National Forest, assembled about 6,000 transparent plastic rectangular panels across one hectare, diverting around 50 percent of the rainfall from the forest floor. They were set 1 meter above ground on the sides to 4 meters above ground in the center. The water was funneled into gutters and channeled through trenches dug around the plot’s perimeter.

Next to it, an identical plot was left untouched to serve as a control. In both areas, instruments were attached to trees, placed on the ground and buried to measure soil moisture, air temperature, tree growth, sap flow and root development, among other data. Two metal towers sit above each plot.

Photo: AP

In each tower, NASA radars measure how much water is in the plants, which helps researchers understand overall forest stress. The data is sent to the space agency’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, where it is processed.

“The forest initially appeared to be resistant to the drought,” said Lucy Rowland, an ecology professor at the University of Exeter.

That began to change about eights years in, however.

Photo: AP

“We saw a really big decline in biomass, big losses and mortality of the largest trees,” said Rowland.

This resulted in the loss of approximately 40 percent of the total weight of the vegetation and the carbon stored within it from the plot. The main findings were detailed in a study published in May in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution. It shows that during the years of vegetation loss, the rainforest shifted from a carbon sink, that is, a storer of carbon dioxide, to a carbon emitter, before eventually stabilizing.

There was one piece of good news: the decades-long drought didn’t turn the rainforest into a savanna, or large grassy plain, as earlier model-based studies had predicted.

FOREST RECOVERY

In November, most of the 6,000 transparent plastic covers were removed, and now scientists are observing how the forest changes. There is currently no end date for the project.

“The forest has already adapted. Now we want to understand what happens next,” said meteorologist Joao de Athaydes, vice coordinator of Esecaflor, a professor at the Federal University of Para and coauthor of the Nature study.

“The idea is to see whether the forest can regenerate and return to the baseline from when we started the project.”

During a visit in April, Athaydes guided journalists through the site, which had many researchers. The area was so remote that most researchers had endured a full-day boat trip from the city of Belem, which will host the next annual UN climate talks later this year. During the days in the field, the scientists stayed at the Ferreira Penna Scientific Base of the Emilio Goeldi Museum, a few hundred meters from the plots.

Four teams were at work. One collected soil samples to measure root growth in the top layer. Another gathered weather data and tracking soil temperature and moisture. A third was measured vegetation moisture and sap flow. The fourth focused on plant physiology.

“We know very little about how drought influences soil processes,” said ecologist Rachel Selman, researcher at the University of Edinburgh and one of the co-authors of the Nature study, during a break.

Esecaflor’s drought simulation draws some parallels with the past two years, when much of the Amazon rainforest, under the influence of El Nino and the impact of climate change, endured its most severe dry spells on record. The devastating consequences ranged from the death of dozens of river dolphins due to warming and receding waters to vast wildfires in old-growth areas.

Rowland explained that the recent El Nino brought short-term, intense impacts to the Amazon, not just through reduced rainfall but also with spikes in temperature and vapor pressure deficit, a measure of how dry the air is. In contrast, the Esecaflor experiment focused only on manipulating soil moisture to study the effects of long-term shifts in rainfall.

“But in both cases, we’re seeing a loss of the forest’s ability to absorb carbon,” she said. “Instead, carbon is being released back into the atmosphere, along with the loss of forest cover.”

Last week the story of the giant illegal crater dug in Kaohsiung’s Meinong District (美濃) emerged into the public consciousness. The site was used for sand and gravel extraction, and then filled with construction waste. Locals referred to it sardonically as the “Meinong Grand Canyon,” according to media reports, because it was 2 hectares in length and 10 meters deep. The land involved included both state-owned and local farm land. Local media said that the site had generated NT$300 million in profits, against fines of a few million and the loss of some excavators. OFFICIAL CORRUPTION? The site had been seized

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

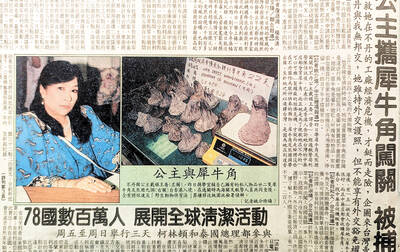

Sept. 15 to Sept. 21 A Bhutanese princess caught at Taoyuan Airport with 22 rhino horns — worth about NT$31 million today — might have been just another curious front-page story. But the Sept. 17, 1993 incident came at a sensitive moment. Taiwan, dubbed “Die-wan” by the British conservationist group Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), was under international fire for being a major hub for rhino horn. Just 10 days earlier, US secretary of the interior Bruce Babbitt had recommended sanctions against Taiwan for its “failure to end its participation in rhinoceros horn trade.” Even though Taiwan had restricted imports since 1985 and enacted

Enter the Dragon 13 will bring Taiwan’s first taste of Dirty Boxing Sunday at Taipei Gymnasium, one highlight of a mixed-rules card blending new formats with traditional MMA. The undercard starts at 10:30am, with the main card beginning at 4pm. Tickets are NT$1,200. Dirty Boxing is a US-born ruleset popularized by fighters Mike Perry and Jon Jones as an alternative to boxing. The format has gained traction overseas, with its inaugural championship streamed free to millions on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. Taiwan’s version allows punches and elbows with clinch striking, but bans kicks, knees and takedowns. The rules are stricter than the