April 14 to April 20

In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals.

The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth called “mountain compatriots.”

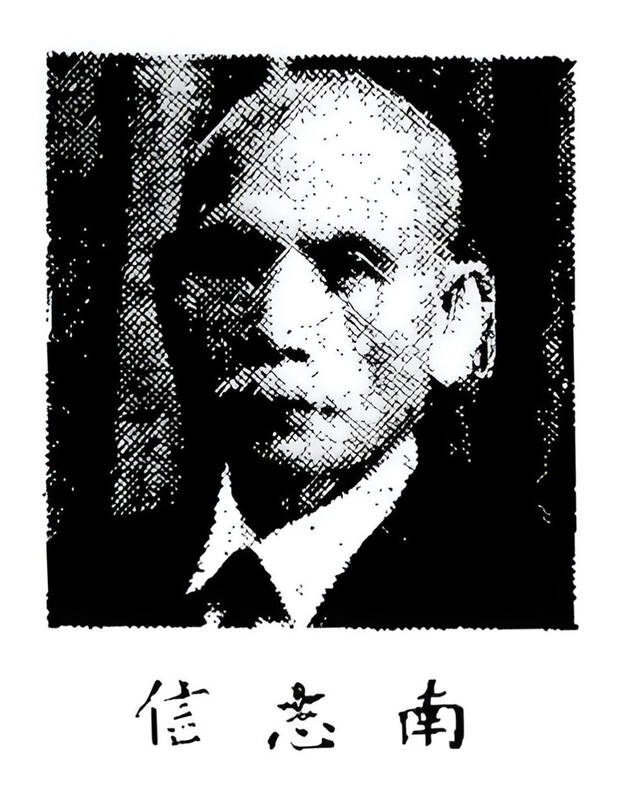

Photo courtesy of National Taitung Living Art Center

Of course, this was from a Han-centric viewpoint, and as so-called “equals,” Indigenous Taiwanese were forced to adopt Chinese names, speak Mandarin and adopt so-called “civilized” ways of living. In essence, this did not differ much from the Qing Dynasty’s “open the mountains and pacify the savages” (開山撫番) policy that began a few years before Sising Katadrepan was born in Taitung on April 18, 1886.

The Qing ceded Taiwan to Japan when Sising Katadrepan was nine years old, allowing him to receive a modern education. In 1909, he graduated from the Medical School of the Taiwan Governor-General (today’s National Taiwan University College of Medicine) and became Taiwan’s first licensed Indigenous doctor.

Sising Katadrepan turned to politics after the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) took over Taiwan, traveling to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Indigenous Taiwanese representative at the National Constituent Assembly and later serving in the Taiwan Provincial Government.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“In a time when the government encouraged assimilation, and when one could easily be arrested for political crimes, he never lost his ethnic identity; by contrast, he proactively fought for the political, economic, health and other interests of Indigenous Taiwanese,” writes historian Agilasay Pakawyan in an article for the Council of Indigenous Peoples.

TIMES OF GREAT CHANGE

Sising Katadrepan was born to a Puyuma family in Puyuma Village (also known today as Nanwang, 南王) in today’s Taitung City. Following the Sino-French War of 1884, the Qing finally realized Taiwan’s strategic importance and began actively governing it as a separate province. Part of this policy was sending troops and officials to Indigenous areas to rule and assimilate the people to Chinese culture.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Culture Memory Bank

The Indigenous people of the east coast did not just accept these changes, plus the officials often abused their power. In August 1888, the Indigenous Taiovan joined forces with Hakka settlers and rose up against the Qing, with the Amis and Puyuma later entering the fray.

The rebellion was crushed within a month, but just seven years later, the Qing were forced to cede Taiwan to Japan. Sising Katadrepan began his formal education in Japanese at the age of 13, and in 1904 he headed to Taipei to study medicine — which was at that time only reachable by boat.

He returned home in 1909 and joined the Taitung Hospital staff, receiving his physician’s license two years later. During this time, he married a Han woman named Wu Lien-hua (吳蓮花) and they had 12 children together.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

HONORED PHYSICIAN

Hospital doctors did not have specialties then, but it’s said that Sising Katadrepan was particularly skilled in treating malaria and scrub typhus. His research in these fields was highly valued by the government, earning him a meeting with crown prince Hirohito when the latter visited Taiwan in 1923.

Sising Katadrepan was later awarded a “gentry medal” for his services, the second Indigenous Taiwanese to receive such honors; reports stated that he was highly respected not just in his community but also among the Japanese and Han.

He was promoted to medical officer in 1929, which likely made him the highest ranked Indigenous person during Japanese rule, Agilasay Pakawyan writes.

“He embodies the honor of the Takasago (Japanese designation for indigenous) people,” the Taiwan Daily News reported.

In 1928, he adopted the Japanese name Shishin Minami and opened the Minami Hospital while still working part time at Taitung Hospital. At his clinic, he often treated those in need for free and provided them medicine. Relatives recall that there were many dogs in his house, as some patients who couldn’t pay for the services insisted on giving him something.

He was known to be very strict with patients who did not care for themselves properly. For example, he admonished and refused to treat those with poor appetite until they had a meal, often cooked by his wife.

POLITICAL CAREER

Under the KMT, Sising Katadrepan became Nan Chih-hsin (南志信), using the Mandarin pronunciation of his Japanese name. Still highly esteemed, he entered politics at the age of 60, first heading to Nanjing to participate in the National Constituent Assembly.

In 1947, he was appointed as a council member of the newly formed Taiwan Provincial Government. He and fellow Puyuma leader Matreli sought to keep the peace among Indigenous communities in Taitung during the 228 Incident, an anti-government uprising that was violently suppressed, and there’s a photo of him and Matreli posing with General Pai Chung-hsi (白崇喜), who arrived in Taiwan as a special representative after the incident to restore order.

As a provincial council member, Sising Katadrepan was tasked with “reassuring and pacifying” the Indigenous communities on the east coast in April 1947.

He spent much of his political efforts working for the betterment of his people, as one of his first acts was to request the government to rectify their designation. If the native people of Tibet and Mongolia could be called Tibetans and Mongolians under the Republic of China government, why couldn’t those of Taiwan simply be Taiwanese?

As a board member of the Taiwan Provincial Mountain Area Development Association, Sising Katadrepan helped establish an “Indigenous hall” on Taipei’s Roosevelt Road for those visiting Taipei to stay and meet. He also worked with renowned pharmacologist Tu Tsung-ming (杜聰明) to train Indigenous doctors at Kaohsiung Medical University.

Finally, he pushed the government to build levees along the Beinan River (卑南溪), reportedly personally meeting with then-president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) to stress how the annual flooding affected locals.

He died on Aug. 13, 1958, and it would be another 36 years until the government finally dropped the hated “mountain” association with Indigenous people.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

As I finally slid into the warm embrace of the hot, clifftop pool, it was a serene moment of reflection. The sound of the river reflected off the cave walls, the white of our camping lights reflected off the dark, shimmering surface of the water, and I reflected on how fortunate I was to be here. After all, the beautiful walk through narrow canyons that had brought us here had been inaccessible for five years — and will be again soon. The day had started at the Huisun Forest Area (惠蓀林場), at the end of Nantou County Route 80, north and east

Specialty sandwiches loaded with the contents of an entire charcuterie board, overflowing with sauces, creams and all manner of creative add-ons, is perhaps one of the biggest global food trends of this year. From London to New York, lines form down the block for mortadella, burrata, pistachio and more stuffed between slices of fresh sourdough, rye or focaccia. To try the trend in Taipei, Munchies Mafia is for sure the spot — could this be the best sandwich in town? Carlos from Spain and Sergio from Mexico opened this spot just seven months ago. The two met working in the