This review has to begin with a confession and a disclosure.

I’m no fan of Taiwanese teas. I don’t think I’ve ever drunk one that I’d go out of my way to buy. Oolong zealots — and I’ve met a good few — have singularly failed to convert me.

One of this book’s co-authors, Katy Hui-wen Hung (洪惠文), is an occasional collaborator of mine; we’ve written a book and several articles together. The other, Hong-ming “HM” Cheng (鄭宏銘), is well known among English-speaking aficionados of Taiwan history on account of “The Battle of Fisherman’s Wharf,” a blog where he compiled hundreds of fascinating stories between 2009 and 2019.

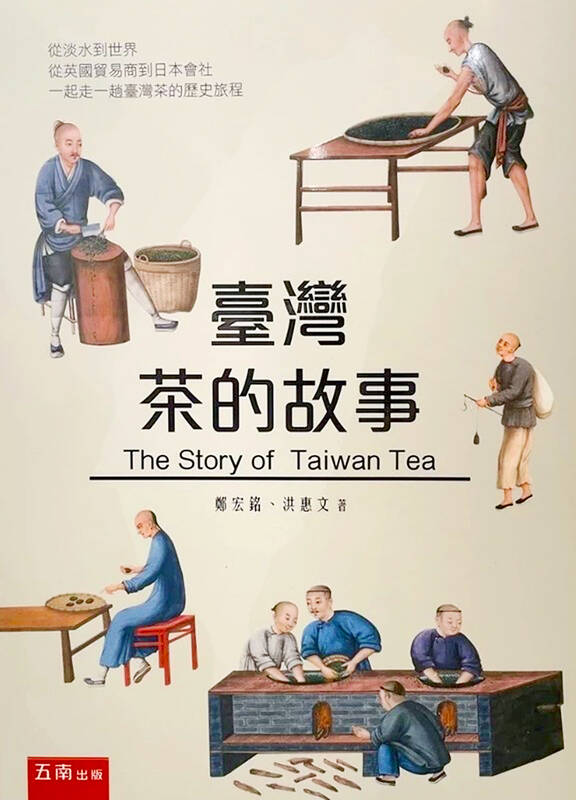

When Hung and I were putting our book together, Cheng was a key source of facts and anecdotes. Accordingly, I picked up this attractive bilingual volume with every expectation it’d be carefully researched and filled with engrossing details, and I wasn’t disappointed.

The 15 chapters in the English-language section (pages 163—272) mirror the Chinese-language content. In order to cram everything in, the publisher opted for a font size so small some readers may find it a problem. This is one distraction; others are weird shifts from one typeface to another, repetitive phrasing and some inconsistencies when it comes to people’s names.

In the space of two pages, we’re told again and again that tea-processing knowledge in China was “closely guarded.” And, just in case you forget, there are frequent reminders that tea leaves require “meticulous” picking and handling.

The wife of Canadian missionary George Mackay is referred to as “Mini,” yet most sources spell her English name “Minnie.” Within two paragraphs on page 198, we’re presented with three different spellings of Zheng Jing (鄭經). Inexplicably, Taiwanese-American botanist Shang Fa Yang (楊祥發, 1932-2007) has his name rendered according to hanyu pinyin.

Zheng’s father, Koxinga (鄭成功) didn’t capture the Dutch East India Company’s Fort Zeelandia (in modern-day Tainan) in 1661, as the book states, but the following year after a long siege. In an otherwise fascinating explanation of how Portugal was overtaken by the Dutch and the British as the leading supplier of tea to Europe, the assertion that “In 1680, Portugal lost its monopoly over Macao to the Qing dynasty,” is misleading on two counts. Nothing happened until 1684-85, when the Qing court began allowing foreign traders to enter Canton and a few other ports, and Portugal’s control over Macao wasn’t in any way diminished.

Despite these gripes, Taiwan obsessives — I can’t speak for tea drinkers — will find The Story of Taiwan Tea a worthwhile addition to their bookshelf, and not just because it’s very possibly the first book-length English-language exploration of its subject.

The authors share some obscure yet delightful nuggets of history, several of which have nothing whatsoever to do with tea.

Following his surrender to the Qing dynasty in 1683, Zheng Jing’s son, Zheng Ke-shuang (鄭克塽), was given safe passage to Beijing on condition that he and his direct descendants never leave the imperial capital; this restriction applied until the fall of the last Qing emperor in 1911 (after which, according to Wikipedia, they “moved back” to Fujian).

A Massachusetts-based dealer in Taiwanese oolong called Charles Arshowe (翁阿紹) became in 1860 the first Chinese person to be naturalized as a US citizen. Kabayama Sukenori, later Japan’s first governor-general of Taiwan, visited the island in 1873 to gather intelligence, disguised as a mute Buddhist monk.

As you might expect, an entire chapter is given over to the pioneering tea traders John Dodd of England and Fujian-born Li Chun-sheng (李春生). Dodd was based in New Taipei City’s Tamsui, a town with which both authors have strong ancestral ties, and the following chapter examines connections between the tea trade and Tamsui’s temples.

Chapter 6 summarizes Robert Fortune’s famously audacious missions that resulted in the British East India Company usurping China’s position as the world’s dominant producer of tea. I didn’t know that Fortune — whose name can be a two-word response to claims that China is always the villain when it comes to IP theft — visited Tamsui circa 1853 to look into the commercial potential of the area’s abundant rice-paper plants (a species unrelated to rice or, for that matter, tea).

One of this book’s strengths is that it doesn’t look merely into the past. The penultimate chapter speculates as to how emerging CRISPR-Cas9 genome-editing techniques could be used to enhance the taste, nutritional content and disease resistance of teas. And, helpfully for those who don’t stay abreast of scientific breakthroughs, it begins by explaining what CRISPR is.

The final chapter is a broader discussion of the future of locally-grown teas, and the authors make several suggestions as to how tea might be able to regain some of the ground it’s lost to coffee over the past few decades. But there’s no need to read The Story of Taiwan Tea from front to back. Quite a few people, I expect, will dip into this book. For that reason, an index would have been a useful addition.

I’m sure I’ll return to the section on the potential health benefits and health risks of tea consumption, which follows a surprisingly accessible deep-dive into the chemistry behind tea flavors. Given Cheng’s background — he’s an ophthalmologist who’s taught at Harvard University — I’m inclined to believe every carefully-chosen word. But I doubt it’ll be enough to get me to drink oolong on a regular basis.

Dec. 8 to Dec. 14 Chang-Lee Te-ho (張李德和) had her father’s words etched into stone as her personal motto: “Even as a woman, you should master at least one art.” She went on to excel in seven — classical poetry, lyrical poetry, calligraphy, painting, music, chess and embroidery — and was also a respected educator, charity organizer and provincial assemblywoman. Among her many monikers was “Poetry Mother” (詩媽). While her father Lee Chao-yuan’s (李昭元) phrasing reflected the social norms of the 1890s, it was relatively progressive for the time. He personally taught Chang-Lee the Chinese classics until she entered public

Last week writer Wei Lingling (魏玲靈) unloaded a remarkably conventional pro-China column in the Wall Street Journal (“From Bush’s Rebuke to Trump’s Whisper: Navigating a Geopolitical Flashpoint,” Dec 2, 2025). Wei alleged that in a phone call, US President Donald Trump advised Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi not to provoke the People’s Republic of China (PRC) over Taiwan. Wei’s claim was categorically denied by Japanese government sources. Trump’s call to Takaichi, Wei said, was just like the moment in 2003 when former US president George Bush stood next to former Chinese premier Wen Jia-bao (溫家寶) and criticized former president Chen

Politics throughout most of the world are viewed through a left/right lens. People from outside Taiwan regularly try to understand politics here through that lens, especially those with strong personal identifications with the left or right in their home countries. It is not helpful. It both misleads and distracts. Taiwan’s politics needs to be understood on its own terms. RISE OF THE DEVELOPMENTAL STATE Arguably, both of the main parties originally leaned left-wing. The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) brought together radicals, dissidents and revolutionaries devoted to overthrowing their foreign Manchurian Qing overlords to establish a Chinese republic. Their leader, Sun Yat-sen

Late one night in April 2020, towards the start of the COVID lockdowns, Shanley Clemot McLaren was scrolling on her phone when she noticed a Snapchat post by her 16-year-old sister. “She’s basically filming herself from her bed, and she’s like: ‘Guys you shouldn’t be doing this. These fisha accounts are really not OK. Girls, please protect yourselves.’ And I’m like: ‘What is fisha?’ I was 21, but I felt old,” she says. She went into her sister’s bedroom, where her sibling showed her a Snapchat account named “fisha” plus the code of their Paris suburb. Fisha is French slang for