April 3 to April 9

With the proliferation of temples across Taiwan, it’s hard to believe that the nation didn’t produce its first local temple painters until the 1920s.

For nearly three centuries, Taiwanese relied solely on visiting artisans from China called “Tangshan Masters” (唐山師父) to do the job, most of them returning home after completing the project.

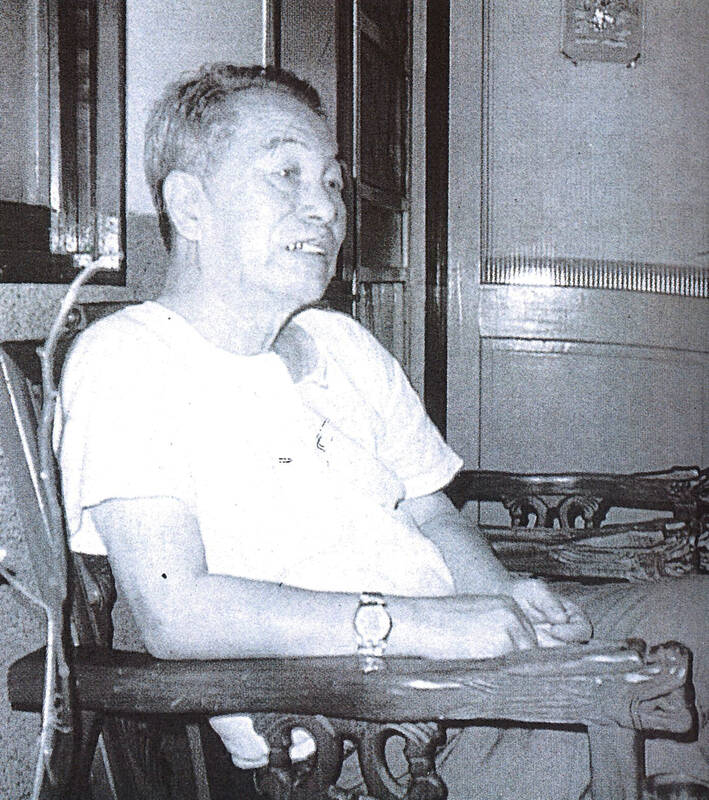

Photo courtesy of Chen Chun-che

This custom started to change after Japan took over Taiwan in 1895, as contact between the two sides of the strait decreased. Seeing an opportunity, a young Pan Chun-yuan (潘春源) secretly observed the Tangshan Masters at work in his hometown of Tainan, and later drew what he saw at home, in an act that was strictly taboo.

In 1909, 18-year-old Pan opened shop on today’s Jhongyi Road (忠義路) and began offering his services as a framer and painter. Between 1920 and 1940, he and Chen Yu-feng (陳玉峰) were the two most sought after temple painters in Taiwan. Unlike Chen, Pan also created contemporary art to exhibit in fine art exhibitions.

Pan Chun-yuan forbade his son Pan Li-shui (潘麗水) to follow in his footsteps, but the younger Pan’s talent was undeniable. In 1931, both were selected to exhibit at the prestigious Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition.

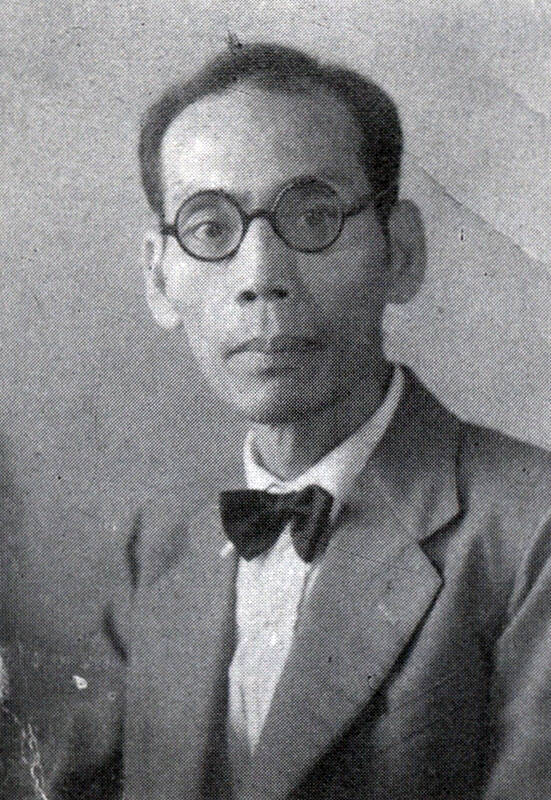

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Pan Li-shui’s career lasted until the 1980s, and with over 1,500 works gracing about 100 temples, he’s considered the most prolific and iconic in the trade.

Pan Li-shui’s son Pan Yue-hsiung (潘岳雄) is still active today and was featured in the Taipei Times article “Temple artist keeps tradition alive at age 80” in November last year.

SELF-TAUGHT MASTER

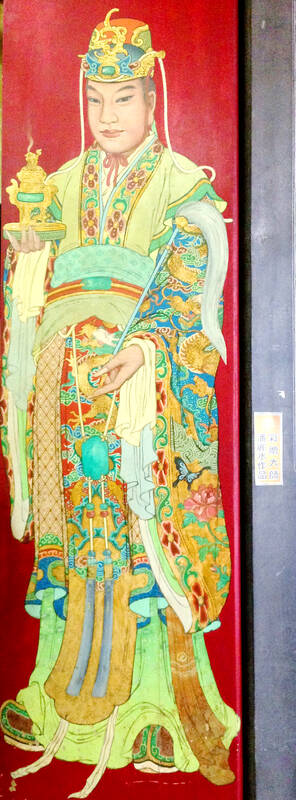

Photo courtesy of Lee Chien-lang

Most Tangshan Masters came from the coastal areas between Guangdong and Zhejiang provinces, and usually stayed for just a few years. It was a respected job and locals treated them well.

They rarely settled in Taiwan as there was not enough work, and never took on local disciples. This was because they only taught family members, and they also wanted to protect their livelihood, according to a report on Pan Li-shui by National Cheng Kung University (成功大學).

One the first to put down roots in Taiwan was the Kuo family (郭), who moved from Quanzhou in Fujian Province to Lukang (鹿港) in the 1860s. The clan of temple painters were active in central Taiwan, the most famous being Kuo You-mei (郭友梅), whose work still survives in a few traditional residences.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“This shows that there were enough temple renovations by then to support the Tangshan Masters to survive in Taiwan long-term,” the report states.

As fewer Tangshan Masters came to Taiwan, talented young Taiwanese began teaching themselves the craft. Pan Chun-yuan only had three years of formal education, but he was well-versed in Chinese literature and there were hundreds of temples in Tainan for him to observe. Only in his 30s did he have the chance to study art for three months in China.

Some believe that Pan learnt traditional Chinese ink painting from artist Lu Pi-sung (呂璧松), who resided in Tainan around 1920 and influenced his style. He was also adept in Eastern gouache and charcoal portraits.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

CHILD PRODIGY

Life wasn’t easy as a traditional Han artist under the Japanese, and the Pan family was not wealthy by any means. Pan Chun-yuan wanted his eldest son to study business and strictly forbade him from making art, but Pan Li-shui continued to do so in secret.

One day, Pan Chun-yuan saw a painting his son had taped to his bedroom door and became furious. But he was also shocked at how good it was. He warned Pan Li-shui that it would be a tough life ahead, but the younger Pan said he didn’t mind. In 1929, at the age of 16, Pan Li-shui formally became Pan Chun-yuan’s disciple.

Photo: Wang Han-ping, Taipei Times

Two years later, Pan Li-shui’s Painting Tools (畫具) was selected, along with his father’s Women (婦女), to participate in the nation’s top art exhibition.

However, Pan Li-shui did not live in as fortunate an era as his father. Shortly after taking over the family business in 1934, the Japanese began their kominka policy and clamped down on Han culture. With almost no temples to work on, in 1940 Pan switched to painting movie banners and posters for local theaters to support his family, although he did create traditional art for private residences and shrines.

Things got worse in 1945 when the Allies began bombing Tainan. Pan fled to the countryside and got by with odd jobs such as grinding sweet potato starch for his brother to sell in the markets.

After World War II, Pan resumed his beloved temple trade while making movie and patriotic propaganda posters for the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) on the side.

By 1954, temple work was abundant enough that Pan quit his movie job. His door gods are especially celebrated, as he designed them so that their gaze followed the visitors throughout the main hall. He was also adept at adapting the drawings to fit any shape and size of door.

The report said his most impressive and iconic creations are the door gods at Kaohsiung’s Sanfeng Temple (三鳳宮), painted in 1969, and the large wall murals in Taipei’s Baoan Temple (保安宮), completed in 1973. Tainan’s Tientan Temple (天壇) is unique in that it contains the work of all three generations.

Pan retired due to poor health in 1985, but continued to participate in local exhibitions. He died on April 8, 1995. His long career spanned two eras, which experts believed contributed to his unique style.

While the Chen clan had faded from the scene by the 1970s, 80-year-old Pan Yue-hsiung carries on his father and grandfather’s craft and insists that he will paint temples until he cannot do it anymore.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.