April 4 to April 10

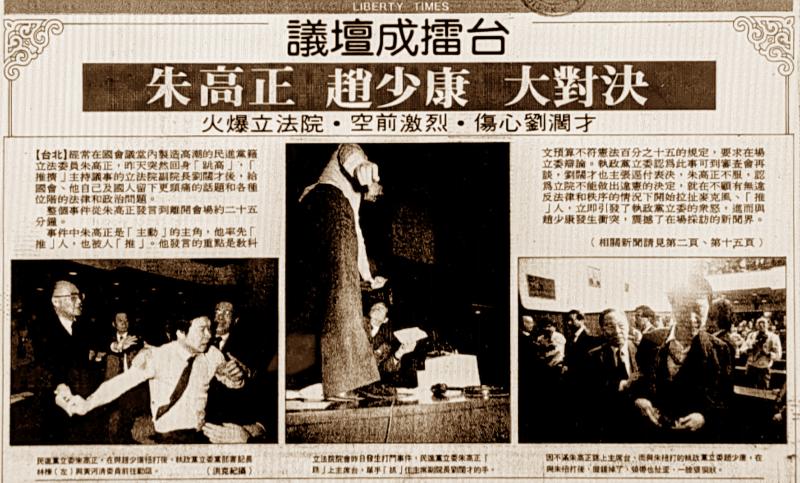

Acting legislative speaker Liu Kuo-tsai (劉闊才) had just begun counting votes on April 7, 1988, when Chu Kao-cheng (朱高正) leapt onto the speaker’s table. As the two struggled, Jaw Shaw-kong (趙少康) climbed over the table to stop Chu, leading to a scuffle that found both of them crashing down the steps to the floor below.

It took more than 10 legislators to pry apart Chu and Jaw, which concluded the first-ever brawl in the Legislative Yuan. Chu’s Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) had reached an impasse with the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) regarding the following year’s budget, and emotions were running high during the extra session.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Liu kept reading the votes amid the chaos, and the budget eventually passed. The KMT’s Jaw took the podium to condemn Chu’s behavior, and Chu hurled a drink at him before storming out.

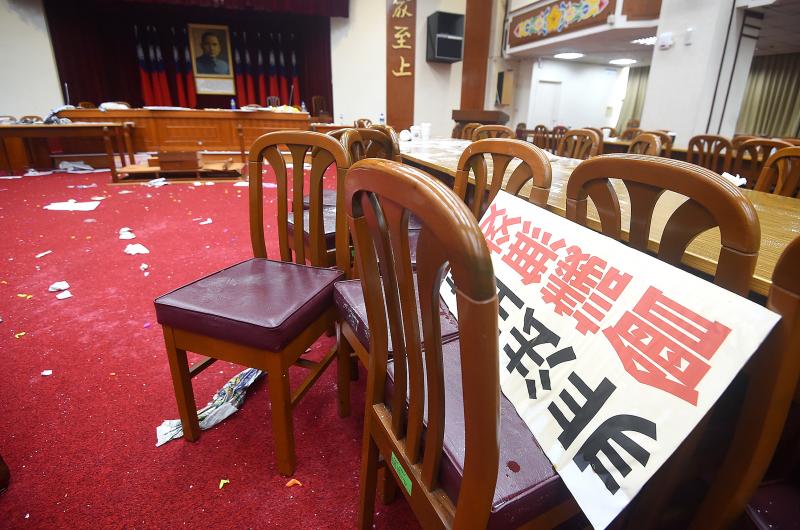

Legislative brawls have since become a tradition, and the international attention the practice has garnered has led many to call it the “shame of Taiwan.” In 1995, the legislature was awarded the Ig Nobel Peace Prize for “demonstrating that politicians gain more by punching, kicking and gouging each other than by waging war against other nations.”

The BBC wrote in a 2017 report: “While parliamentary brawls occur occasionally in other countries, Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan is notorious for them.”

Photo: Liu Hsin-de, Taipei Times

A Washington Post article shows that there were 240 scuffles between 1987 and 2019.

Chu, who was later expelled from the DPP and formed his own party, was notorious for his fiery temper and penchant for violence. Five months earlier, he threw legislator Chou Shu-fu (周書府) to the ground after being repeatedly interrupted, although Chu claims that Chou pushed him first. Chu insisted that extreme measures were the only way to combat the KMT, whose authoritarian rule had only ended on July 15, 1987, with the lifting of the ban on new political parties.

The April showdown was shown on national television and was plastered on the front of major newspapers, setting an unfortunate tone for Taiwan’s fledgling democracy.

Photo: Liao Chen-hui, Taipei TImes

FIGHTING FOR A CAUSE

Criminologist Chang Sue-chung (張淑中) writes in the 2010 book Legislative Violence: Criminal Theories, Cases and Countermeasures (國會暴力:犯罪理論,案例及對策) that the blame for the violence falls on the two major parties failure to compromise on contentious issues.

“The majority party refuses to negotiate, and the minority party refuses to give up,” he writes, noting the decades of bad blood between them.

Photo: Liao Chen-hui, Taipei TImes

In an analysis of a 2005 incident over the establishment of the National Communications Commission, Chang writes: “The two sides insisted on taking a tough stance and were unwilling to budge. But aside from the opposing versions of the bill, there were many examples of such commissions throughout the world they could have examined.”

There was also a bill sponsored by civic groups, but both sides refused to consider it.

STRATEGIC VALUE

Photo: Liao Chen-hui, Taipei TImes

Brawling also has strategic value. It’s a way to garner media attention — and the media loves a good dust up. It’s a display for the party’s die-hard constituents, stirring up emotions and showing how far their representatives are willing to go to safeguard their interests, Chang writes.

Chu’s provocative attitude was also calculated.

“Politics is the highest form of trickery,” he often said, and he believed that swearing and fighting had its place if used appropriately.

Photo: Liao Chen-hui, Taipei Times

“Swearing can make someone appear to lack self-cultivation,” Chu once said. “But if you master the timing and use vulgar language appropriately, then the effect can be miraculous.”

In 1987, the Legislative Yuan still had members who had been in place since 1947 due to Martial Law provisions, and Chu saw these “thousand-year congresses” as the main obstacle to democracy.

“I became the top vote-getter in Yunlin, Chiayi and Tainan on one promise: ‘If you vote for me, I guarantee that I will explode a bomb in the legislature. I will ... smash the mountains, crack the earth and overturn the heavens. Until the KMT agrees to hold full elections, I will not let up,’” he declared to the aging lawmakers. “My purpose in being here is to send you home so you can enjoy your retirement.”

In his memoir, he recalls launching the April 7 attack because the KMT was about to force through a budget that even they admitted was unconstitutional.

CONSEQUENCES?

In the early days, it was common for the legislative speaker to summon the police to restore order. The first time this happened was in December 1988, when a melee erupted over eliminating the “thousand-year congress.”

The last time the cops were called to the legislature was in April 1991. They didn’t even enter it when it was occupied by hundreds of protestors during the 2014 Sunflower movement.

There is no law that clearly defines the speaker’s legal options in the event of an altercation among legislators. The legislature does have a disciplinary committee that can punish unruly lawmakers, but Chang writes that it’s ineffective. The body handed out just one punishment before 2001, suspending Wei Hsi-yen (魏惜言) for six sessions for throwing his papers on the floor and swearing at then-speaker Huang Kuo-shu (黃國書). The problem, Chang writes, is that the committee is made up of legislators, who are reluctant to punish their own party members.

Chang proposes that those who repeatedly incite violence should risk losing their seat. Japan, the US and Sweden are among the countries that have this provision, with the decision made by a two-thirds vote.

“Only by seriously punishing offending legislators can we deter violence in the legislature,” he writes.

Chang concludes that voters and watchdog groups should hold violent legislators accountable by, for example, publicizing during election season which ones are prone to inappropriate behavior. Voter education is also important, so that people can make informed decisions instead of being swayed by disinformation, sensationalism and their own personal gain.

“People should be aware that through their vote they have the power to punish candidates with histories of violence,” he writes.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

Specialty sandwiches loaded with the contents of an entire charcuterie board, overflowing with sauces, creams and all manner of creative add-ons, is perhaps one of the biggest global food trends of this year. From London to New York, lines form down the block for mortadella, burrata, pistachio and more stuffed between slices of fresh sourdough, rye or focaccia. To try the trend in Taipei, Munchies Mafia is for sure the spot — could this be the best sandwich in town? Carlos from Spain and Sergio from Mexico opened this spot just seven months ago. The two met working in the

Many people in Taiwan first learned about universal basic income (UBI) — the idea that the government should provide regular, no-strings-attached payments to each citizen — in 2019. While seeking the Democratic nomination for the 2020 US presidential election, Andrew Yang, a politician of Taiwanese descent, said that, if elected, he’d institute a UBI of US$1,000 per month to “get the economic boot off of people’s throats, allowing them to lift their heads up, breathe, and get excited for the future.” His campaign petered out, but the concept of UBI hasn’t gone away. Throughout the industrialized world, there are fears that